One standout achievement defines Javier Milei’s first 100 days as Argentina’s president: the country’s budget has swung into surplus territory for the first time in 12 years. It’s a significant milestone for Milei, who pledged bold reforms to a populace weary from enduring years of economic turmoil, and so far, he’s delivering on his promises. Milei tackled the deficit head-on by scrapping social benefits and pension indexing, resulting in a noteworthy rise in poverty levels, which have hit a 20-year high as the country’s poorest find themselves without a social safety net. Despite the positive fiscal start, Milei urges patience, cautioning that it will take time before the economy sees substantial improvements. The road ahead for further reforms is fraught with challenges, as Milei lacks control over the country’s parliament, and powerful unions are resisting change.

Two peculiarities define Argentina's new president, Javier Milei: his unconventional hairstyle and his self-identification as a “philosophical anarcho-capitalist.” In practice, however, Milei has been compelled to adopt a kind of minarchist stance, advocating for minimal government intervention in society rather than an outright abolition of the state. Milei's background as a libertarian activist, known for his eccentric attire and scathing critiques of the political elite, underscores his lack of executive experience (aside from his tenure as a parliamentary deputy, where his attendance was sporadic).

Milei's symbolic use of a chainsaw during rallies and election campaigns encapsulates his vision for Argentina's government under his leadership. True to his word, Milei wasted no time in office, swiftly dismantling nine out of eighteen government ministries, axing over 5,000 civil service positions, and pledging to privatize state-owned enterprises. Proponents of Milei's approach argue that these measures will mitigate the unsustainable government budget deficit, potentially attracting greater foreign investment and earning the approval of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), a perennial source of financial support for Argentina.

The concerted efforts seem to have paid dividends: by the end of January, the IMF Executive Board greenlit Milei's request, allocating $4.7 billion to “bolster decisive policy initiatives aimed at restoring macroeconomic stability.”

Milei also astounded the world in January by reaching Argentina's first budget surplus in 12 years, totaling $589 million. The key to this fiscal success lies in stringent economic measures: he trimmed allocations to provinces, halted subsidies, and eliminated pension and welfare adjustments. Consequently, poverty levels soared to a staggering 57.4% in January, marking a two-decade high, with approximately 27 million Argentines now living below the poverty line — 15% of them in extreme poverty, struggling to afford basic necessities. Despite these grim statistics, Milei appears undeterred, emphasizing that his economic strategies will continue to inflict considerable short-term pain on ordinary citizens before reform is achieved.

Meanwhile, inflation decelerated from 25.5% in December to 13.2% in February, prompting Milei to express optimism about a further downward shift. However, economic activity has also been on the decline, with January industrial production contracting by over 12% year-on-year.

In a recent interview, Milei asserted his determination to secure approval for an extensive presidential decree comprising over 300 economic reforms, vowing to fulfill all his campaign promises regardless of staunch opposition from rival parties in parliament. Why did he decide to resort to such radical measures, and how justified are they?

Counted among the world’s wealthiest nations at the dawn of the 20th century, Argentina eventually fell into hyperinflation, ultimately emerging as the International Monetary Fund's (IMF) largest borrower. While the IMF is often criticized for its stringent loan conditions, in Argentina's case, creditors are faulted for what is perceived as lax policies.

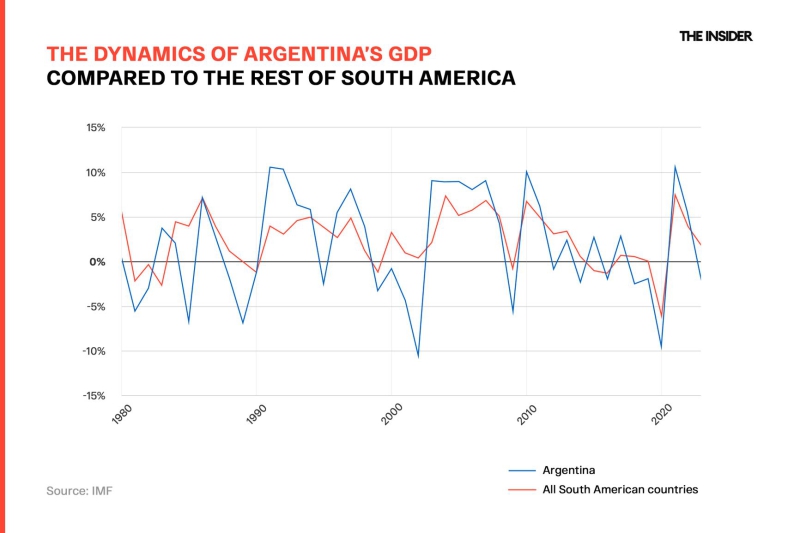

Relative to developing nations, Argentina has seen respectable economic growth in recent decades, boasting a GDP per capita that outstrips Brazil and even slightly edges out Russia's. However, this progress is marred by persistent instability. Despite an overall trajectory of respectable growth since 1980, Argentina has weathered periods of severe downturns, complicating long-term planning for both citizens and businesses ever conscious of the need to brace for the next economic slump.

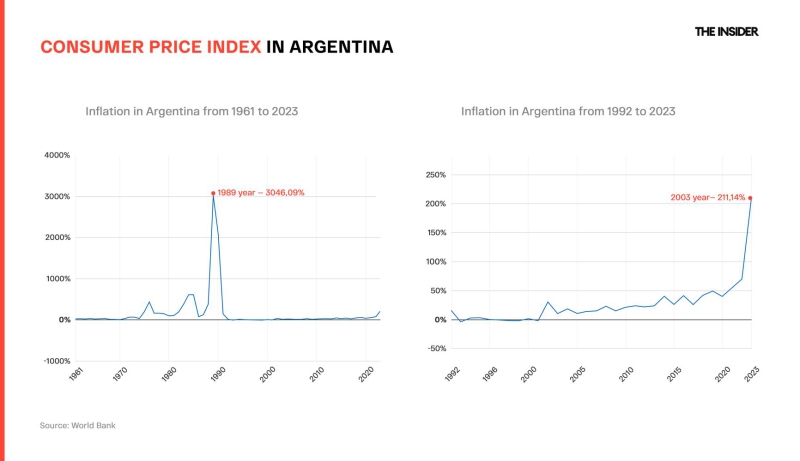

At the heart of Argentina’s woes lies its chronic inflation, which plagues the economy for decades. In 1989, inflation soared to a staggering 3000%, and in 2023, it hit a three-decade high of 211%. To cope with incessant price hikes, retailers have turned to electronic price tags for easier adjustments.

The roots of such price hikes can be traced back to populist policies. Arguably, the most influential political figure in Argentina's history was Juan Perón, who served as the country's president after World War II. He championed social equality, economic nationalism, and anti-internationalism. During his presidency, the government took an active role in the economy, nationalizing banks and major enterprises and implementing extensive and costly social welfare programs. Initially, these expanding government expenditures seemed effective; however, they quickly led to budget deficits and the uncontrolled printing of money, resulting in economic decline and the devaluation of the peso.

Peronists have held power for sixteen of the last twenty years, consistently advocating for protectionism and Argentina's economic isolation to shield against foreign competition. This stance diminished the country's share in global trade.

Under Peronist rule, the country’s public sector expanded significantly, reaching a state in which one in every five workers was employed by the government. Extensive subsidies to domestic producers drained the treasury for decades without improving the quality of goods or the lives of the impoverished population. Instead, they exacerbated economic disparities.

Milei's plan is ambitious: to expand market freedoms, open up trade with the world, and adopt the U.S. dollar as the national currency. Essentially, it’s a form of shock therapy, a method used by various countries — most notably those of the former Eastern Bloc after the fall of the Soviet Union — to swiftly transition from planned to market economies. It's like throwing someone into deep water to teach them how to swim. Under Milei's plan, state intervention would be minimized, state-owned assets privatized, and taxes raised. Additionally, the new president intends to dismantle national protectionist policies, advocating for competition as the driving force: “We’ll have to compete — earn our bread by the sweat of our brow or face bankruptcy!”

We’ll have to compete — earn our bread by the sweat of our brow or face bankruptcy!

However, this approach has met resistance, particularly from industrialists who argue they are unprepared to compete under such conditions, fearing they would be handicapped on the global stage.

Previous Argentine administrations, like that of President Mauricio Macri, who won the 2015 elections, pursued more gradual economic reforms. Macri negotiated with creditors, restored Argentina's access to international borrowing markets, and accumulated debt in the process. He also made efforts to reduce subsidies and export taxes on agricultural products in order to stimulate production and trade. Still, he stopped short of implementing more aggressive cuts to expenditures.

Another significant aspect of Milei's plan is the elimination of subsidies. The rationale is clear: subsidies distort market prices, hinder efficiency, and burden the government, ultimately fueling inflation. For example, if electricity, historically subsidized in Argentina, is sold at below-market rates, there's little incentive for power plants to increase production. As a result, maintenance of the power grid suffers, and consumers use energy wastefully. While subsidies aim to shield people from inflation, they end up exacerbating it by forcing the government to print more money, perpetuating a vicious cycle of economic instability.

Milei is also pushing for privatization and the transfer of “all state agencies that can be privatized, as soon as possible” to market control. He’s leaving no stone unturned, even in the realm of healthcare. By his decree, price controls on medicines and health insurance were lifted, resulting in a 40% increase, making them unaffordable for many patients.

However, Milei's primary and most radical objective is to ditch the Argentine peso in favor of the U.S. dollar, a move known as dollarization. This strategy has been developed with the input of notable economists including Steve Hanke and John Cochrane, who believe that by stripping the Central Bank of its ability to print money (and thereby stoke inflation), the economy can be stabilized.

Argentina’s banking system is relatively small given the size of its economy, making it challenging to secure domestic financing for budget deficits. As a result, authorities typically turn to foreign borrowing. This poses a problem because the country's exports are relatively low, a consequence of the isolationist policies of Peronism, and there simply is not enough currency inflow to service the existing debt.

Economist Brad Setser drew a parallel between Milei's decision to dollarize the economy — thereby preventing the Central Bank from driving up inflation by printing money — and Odysseus instructing his sailors to tie him to the ship's mast so that he could thereby resist the allure of the Sirens’ without covering his ears. Essentially, Milei is tying the hands of his government to resist the temptation to resort to printing more money.

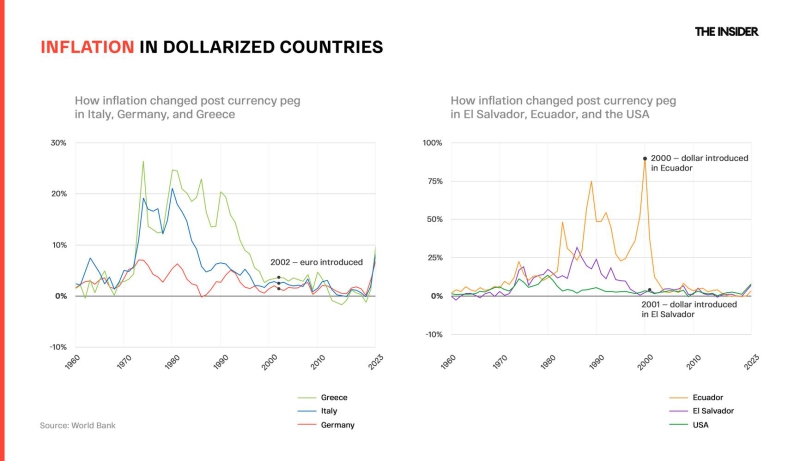

Looking at examples of other countries that have adopted dollarization, it is evident that this is an effective tool in combating inflation. European nations like Italy and Greece, for instance, saw inflation drop significantly after transitioning to the Euro, while South American countries like Ecuador and El Salvador experienced similar success after dollarizing their economies.

Consider Argentina itself as an example: in 1991, the peso was already pegged to the dollar. This was implemented through a currency board — a monetary policy regime in which the government pegs its currency to another and commits to unlimited exchange of the national currency for the “anchor” foreign currency at a fixed rate. So long as foreign currency reserves are maintained at a sufficient level to fully cover obligations (meaning if 1 million pesos circulate in your economy, you must hold at least $1 million in reserves, preferably 10-15% more), such a regime differs from full dollarization only in that it is easier to abandon, as there is no need to “reintroduce” the domestic currency.

In Argentina’s history, there are examples of such an arrangement proving beneficial — thanks to a currency peg, inflation in the country plummeted from 3000% in 1989 to a mere 3% in 1992. However, the Argentine government struggled to sustain such a regime, leading to its abandonment in 2002. That’s why Milei and his supporters are now advocating for the full dollarization of Argentina.

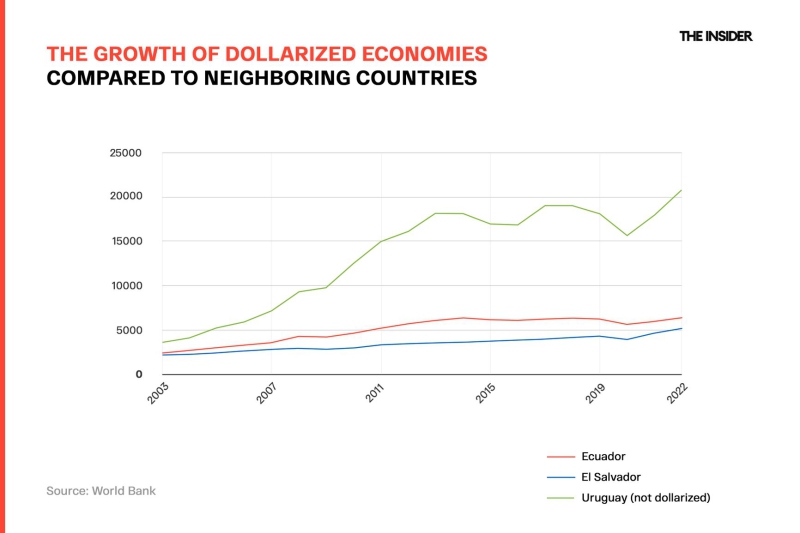

Will dollarization help revitalize the economy and lead it towards stable growth? The answer is uncertain. In fact, such a policy may exacerbate the situation. A recent study examining countries with dollarized economies concluded that, on average,

dollarized countries experience slower and more volatile economic growth, despite having lower inflation rates compared to non-dollarized counterparts.

An examination of Ecuador and El Salvador is instructive. While both have successfully curbed inflation, their economic growth has significantly slowed, with Ecuador even experiencing complete stagnation since 2014.

While Milei's plan to dollarize Argentina has garnered support from several prominent economists, the prevailing view sees this practice as detrimental and advises countries to retain their own currency, with its exchange rate determined by market forces. Exchange rates typically serve as a buffer against external shocks, affording the country greater flexibility to manage its economy effectively.

Consider the potential scenario in which the United States abruptly hikes interest rates due to domestic inflation. In such a case, capital flows into the U.S., where investors can secure higher returns, would increase. If Argentina fully adopts dollarization, capital will drain from the country unless it also raises its own interest rates, potentially leading to adverse consequences.

Another drawback of dollarization is that strict fiscal discipline is not always the best policy. If a crisis strikes and the Central Bank can no longer rescue the government and banking system by expanding the money supply, the only recourse would be a regime of severe austerity: significant tax hikes, wage reductions, pension cuts, and other spending reductions. Overall, this approach is less effective than prudent monetary policy.

Furthermore, dollarization necessitates access to dollars. However, Argentina lacks an adequate supply. Although Argentines may hold substantial sums in mattresses and offshore accounts, the central bank lacks sufficient U.S. currency to cover the country's existing debt, let alone replace the peso in circulation. Consequently, if dollarization were to occur, it would likely unfold gradually, spanning several years.

Even advocates of dollarization concede that this strategy is not a panacea and could likely only be effective as a temporary measure. They argue that dollarization will attract investments, facilitating the transformation of Argentina’s economy into a modern, stable, and prosperous system so developed that not even central bankers could easily wreck it again. Under such circumstances, the country could eventually transition back to its own currency.

It is not feasible for Milei to implement his ideas solely through presidential decrees. The majority of his proposals must navigate through Congress, where other parties hold sway. Almost immediately, the reform agenda encountered hurdles. Congress halted the adoption of hundreds of measures proposed by Milei. Nonetheless, the president refuses to concede defeat on reforms: he addressed Congress, vowing to implement his plans at any cost. In the worst-case scenario, he could wait for the 2025 midterm legislative elections, aiming to secure a majority for his party in Congress before making another attempt with a comprehensive package of changes. However, Milei has stated his readiness to advance a significant portion of his reform program even without Congress’s support.

Analysts caution that the key to Milei's success hinges on how long the poorest Argentinians, who have already endured skyrocketing prices, will tolerate the measures of harsh austerity and the cancellation of government support and control. The termination of funding for 38,000 free cafeterias has already sparked protests across the country.

Amidst the economic shakeup, the Confederation of Trade Unions of Argentina staged a nationwide strike against the government. However, Milei urges the people “to be patient and have trust,” arguing that “it will take some time before Argentina can feel the benefits of the economic reorganization and reforms that we are implementing.”

IMF Deputy Managing Director Gita Gopinath acknowledges that the economy inherited by this government was on the brink of crisis and required bold and decisive actions to save it from collapse. However, austerity measures must be “calibrated to ensure that social assistance continues to be provided and that the burden does not fall entirely on the poorest groups,” she says.

Milei faces a dilemma: should he uphold his promises of radical reforms in an attempt to save the economy, or should he abandon some ambitions while retaining voter support, thereby mitigating the consequences for ordinary Argentines? Milei's risks are high, as the country is known not only for its hyperinflation, but also for its revolutions.