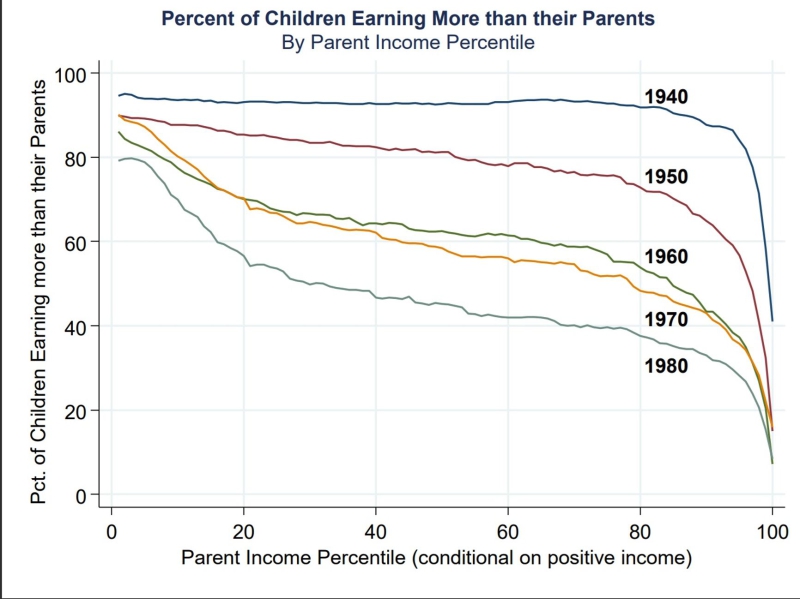

The declining levels of trust in political institutions and the growing support for populist politicians observed in a range of counties in recent years may have economic roots: global economic growth has stopped automatically translating into middle-class prosperity. For millennials and the children of Gen Z, the social elevator has not merely slowed down — it has stalled on the lower floors. In the United States, the likelihood that a child will ultimately earn more than their parents has fallen from 90% for those born in the 1940s to 50% for the 1980s generation. On paper, incomes are rising, but inflation in the key “tickets to the middle class” — housing and education — is outpacing wage growth severalfold, rendering the standard enjoyed by previous generations unattainable to an increasing proportion of young people. In Russia, this global trend has taken the form of “well-fed poverty.” While state regulation of prices for the “borscht basket” curbs the threat of hunger and absolute destitution, the cost of essential assets — from real estate to healthcare and cars — has become prohibitively high.

In the history of economic thought, the period from the end of World War II to the mid-1970s is referred to variously as the “Golden Age” or the “Great Compression.” During this time, indicators for labor productivity growth and real wages moved in lockstep: if a worker began producing more parts per hour thanks to technological advances, their hourly pay increased in almost the same proportion.

By the late 1970s, however, a very different phase had begun. At the suggestion of Paul Krugman, it is now called the “Great Divergence.” According to data from the Economic Policy Institute, from 1979 to 2022 labor productivity in advanced economies rose by 64.7%, while hourly pay for rank-and-file workers increased by only 14.8%. This means that while the overall economy became more efficient, the excess profits went to owners and top management rather than to those who make the product.

At the same time, most countries succeeded in eliminating absolute destitution. That success created an illusion of prosperity that obscures the real problems facing the middle class. According to data from the World Bank, the global extreme poverty rate fell from 44% in 1980 to less than 10% in the 2020s, and in advanced countries, the figure is close to zero. Whereas in the 1950s and 1960s many parts of Europe and the United States still had pockets of chronic undernourishment, today government social protection tools provide a basic safety net.

The global extreme poverty rate fell from 44% in 1980 to less than 10% in the 2020s, and in advanced countries the figure is close to zero

Today, the average resident of an advanced country consumes more calories and enjoys a more varied diet than the affluent classes of 19th-century Europe did, as historical data from Our World in Data show. Meanwhile, the main marker of poverty — the share of total consumption that the average family spends on food — has declined from 50% in the mid-20th century to just 10–15% in advanced countries today. (Notably, Russia lags behind on this measure, with Rosstat putting the figure for the country at around 35%.)

Moreover, goods that were once considered luxury items have turned into inexpensive mass-market products. This happened thanks to globalization and the relocation of manufacturing to countries with cheap labor — first China, and now other Asian nations as well. The cost of household appliances, clothing, and furniture has plummeted. Today, a smartphone with computing power exceeding that of NASA’s 1970s computers is available to almost everyone.

All this creates an image of “universal prosperity,” but a person may be “well fed” yet still be completely cut off from the mechanisms of social mobility. The money freed up by advances in technology and logistics was supposed to make people richer, but instead it was largely absorbed by the ballooning cost of “development assets” — housing, healthcare, and education.

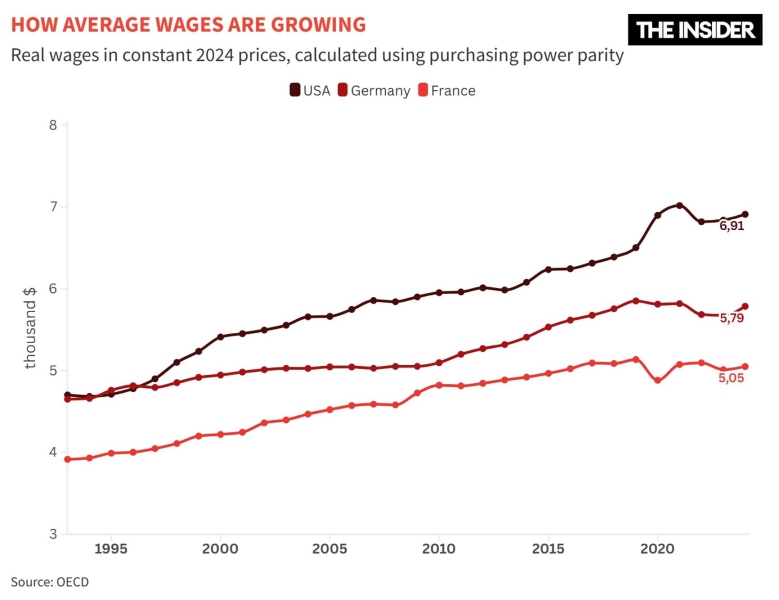

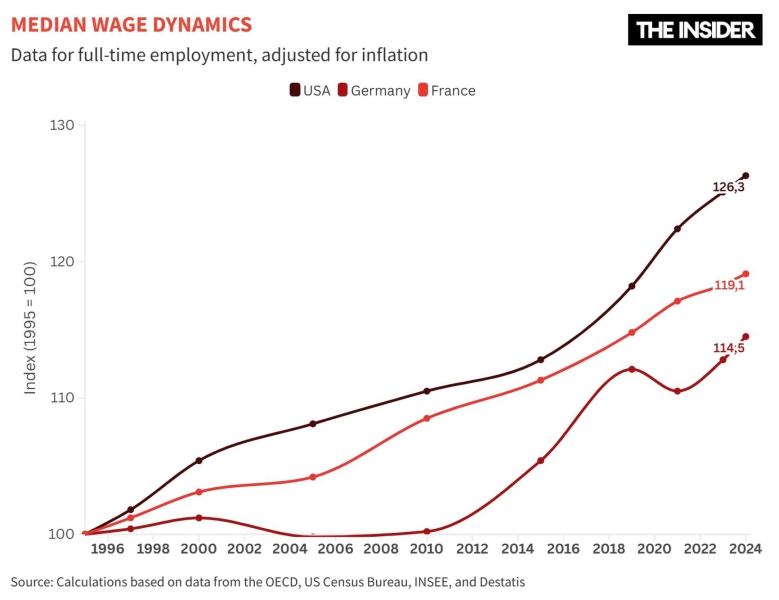

Politicians often point to the fact of rising nominal wages, which in the United States have more than doubled since 1995. However, once these figures are adjusted for overall inflation, real income growth amounts to about 50% in the United States and just 34% in France. The problem is that real estate, tuition, and medical treatment have risen in price even faster than incomes have.

While 90% of children born in the United States in the 1940s were already earning more than their parents did at age 30, among Americans born in the mid-1980s only 50% managed to reach that threshold. If male incomes are assessed separately, the picture is even more discouraging: by age 30, fully 95% of men born in 1940 earned more than their fathers had at that age, compared with just 41% of those born in 1984.

As a result, American adults are largely dissatisfied with their financial situation. About 75–80% believe that it will be harder for today’s children to achieve financial success than it was for their parents. The cost of homeownership relative to income has nearly doubled even compared with the not-so-distant 1990s. People see that by age 30 their mothers and fathers already owned homes and had stable families. At the same age, many today are still paying off student loans and sharing rented housing.

Today, more than a quarter of Europeans (28%) consider their financial situation unstable, and from 1995 to 2019, labor productivity in the eurozone rose by 28%, compared with 50% in the United States over the same period. In addition, real purchasing power in Europe has stagnated for decades.

Real purchasing power in Europe has been stagnating for decades

In the United Kingdom, 56% of citizens born before 1975 outperformed the previous generation in terms of income, but among younger Britons that share fell to 33%. Sweden is an exception: 84% of men and 86% of women earn more than their parents did at comparable ages. This is one of the highest rates in the region and is explained by the country’s historically low level of inequality.

Russia’s “Great Divergence” was delayed. In the 2000s, amid high global oil prices, wages in the country actually outpaced productivity growth. The situation returned to normal for a while, but since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, labor shortages have led to a “wage race” that, once again, was not the result of higher efficiency. It may seem that, under the circumstances, Russia’s middle class has a chance to grow wealthier and realize the “American Dream.” In reality, however, that opportunity is limited to a small number of residents in large cities, while income growth for the rest of the population remains very modest.

Let us examine how living standards have changed using the examples of the United States, France, and Germany — three highly developed Western economies that have employed different models in the course of their recent development. The U.S. is a distinctly liberal economy with high labor mobility, and limited government involvement, with the state primarily responsible for enforcing players’ adherence to the “rules of the game.” France is a social-democratic system, with significant constraints on employers, a progressive tax scale in which the wealthy pay more, a developed welfare system, and broad state intervention in the market. Germany occupies an intermediate position (though it is closer to the French model than to the American).

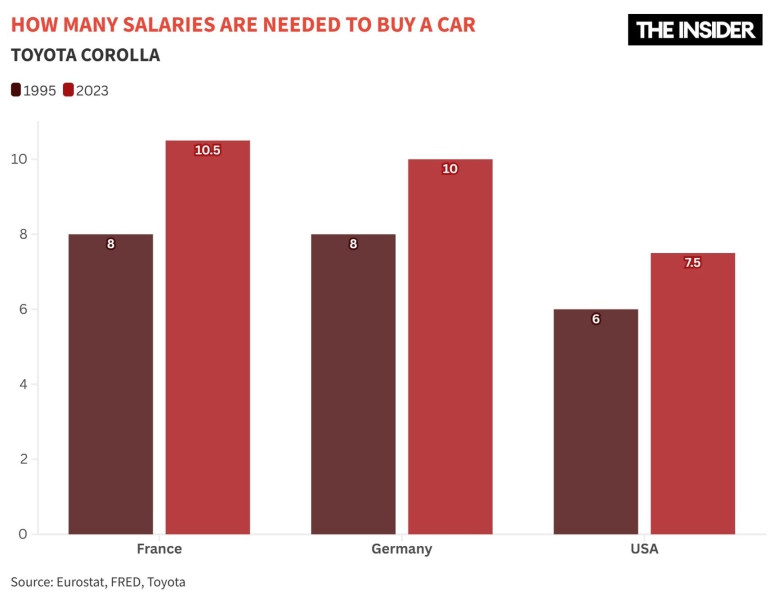

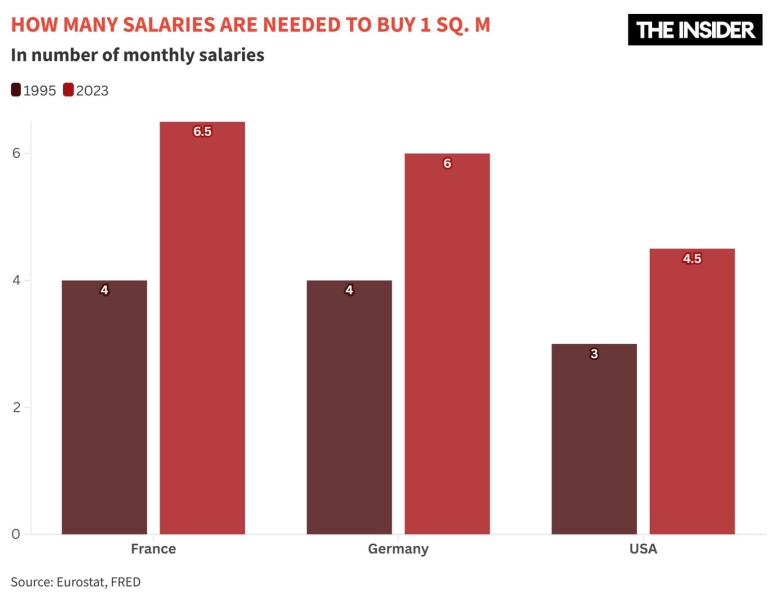

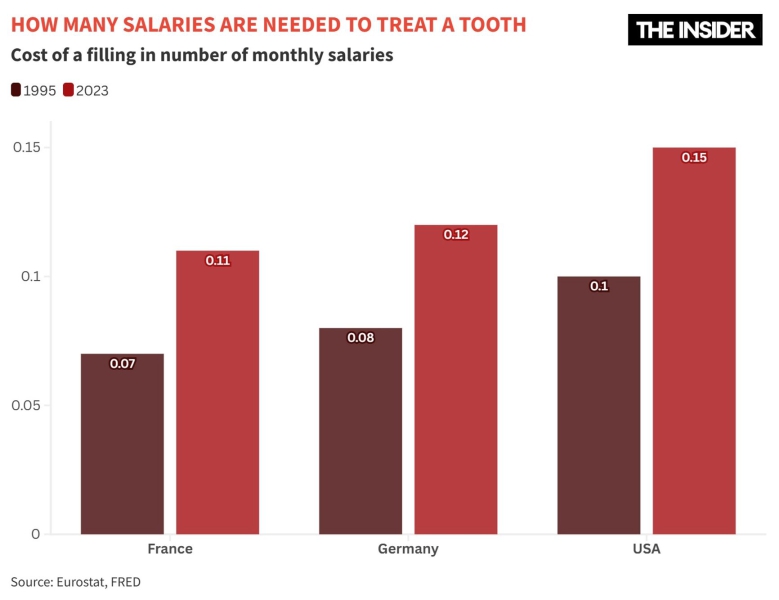

To determine whether broad segments of the population are in fact becoming poorer, we will look at the dynamics of nominal and real wages adjusted for inflation and calculate how many average salaries in each country are required to purchase one square meter of housing, a Toyota Corolla, and basic dental treatment. These calculations are, of course, very approximate, but they help illustrate the overall picture.

Over the past 30 years, nominal wages have risen in all three countries. In America, the average annual salary was about $35,000 in 1995 and more than $81,000 in 2023 – an increase of roughly 130%. In France over the same period, the average nominal salary rose from €25,000 to €43,500 per year – up 57%. In Germany, it increased from €42,000 to €48,300 — about 15%. In terms of real growth, the United States also led: over the past 30 years, wages there have risen by 10–15%, compared with 5–10% in Germany and France.

In other words, real wages are rising, albeit slowly, and median wages are increasing as well.

At first glance, the data would suggest that most people should be getting wealthier. Paradoxically, however, over the past 20 years the cost of essential goods, many basic services, and housing have become relatively less affordable in all three countries. Even in the United States, where wage growth has been particularly noticeable, buying a car now requires more average salaries than it did 20 years ago.

Housing affordability has declined even more sharply. Across the EU, real estate prices rose by 50% over the past 15 years (2010–2025), while rents increased by 25%, pushing the price-to-income ratio up by 20–30%. In the United States, the house price index has increased by 100–150% since 1995 — meaning it now costs the equivalent of four to six monthly salaries per square meter, compared with three in 1995. In the EU, peak housing inflation (23.3%) was recorded in 2022. This has led to an affordability crisis in which one in ten Europeans spends more than 40% of their income on housing.

Services are more difficult to measure, as trends vary widely by category, but dentistry — one of the most universal medical services — has also become less affordable.

This trend inevitably affects public sentiment. While Elon Musk prepares to become the first trillionaire in history, the average family understands that paying off a mortgage may take the rest of their lives. The recent wave of inflation, triggered by the coronavirus pandemic and rising energy prices amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine, has made the problem particularly acute.

Russia does not fit neatly into the broader trend, having followed a distinct path: first a command economy, then an emerging and unstable market, then an oil superpower, and finally a heavily regulated wartime economy.

Real wages in Russia rose alongside oil prices in the early 2000s, but growth slowed after the 2008 crisis. Following the annexation of Crimea and the first round of sanctions, wage growth first stalled, then partially recovered, only to be cut back again after the start of the full-scale invasion in 2022. In dollar terms, Russian wages rose even faster, and also fell more dramatically.

Paradoxically, Russians combine a belief that things are not so bad (after all, official statistics assert that real wages continued to grow in 2025) with deeply negative expectations for the future. The explanation may lie in a recurring historical pattern: periods of rising prosperity in Russia have consistently been followed by sharp downturns. At the same time, in terms of living standards, the past 20 years have been remarkably stable.

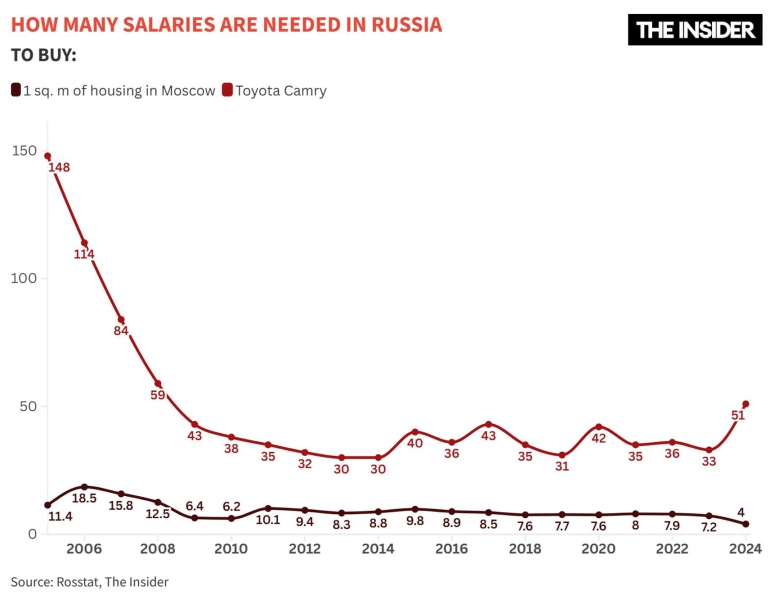

If we look at the affordability of specific goods and services, life for Russian citizens improved far more significantly in the early 2000s than it did for populations in Western countries. This was not only due to the rise in oil prices but also to the effect of a low starting point: both arithmetically and psychologically, growth from near-zero levels appears much more substantial than growth from already high indicators. However, since the late 2000s, the impact of that growth has largely faded. As an example, consider the Toyota Camry: in 2005, purchasing such a car cost Russians 150 average monthly salaries; by 2010, that figure had fallen to just 38 and hovered around that level for more than a decade; then the full-scale invasion saw it jump to 51.

A similar dynamic can be observed in housing. Real estate prices, which seemed to fluctuate dramatically, in fact largely mirrored wage levels, meaning that little changed for Russians when it came to long-term affordability. In 2005, one square meter in Moscow cost the equivalent of 11 monthly salaries. Affordability then declined for several years before returning to that level in the early 2010s, remaining there until the start of the full-scale war — after which it actually improved slightly.

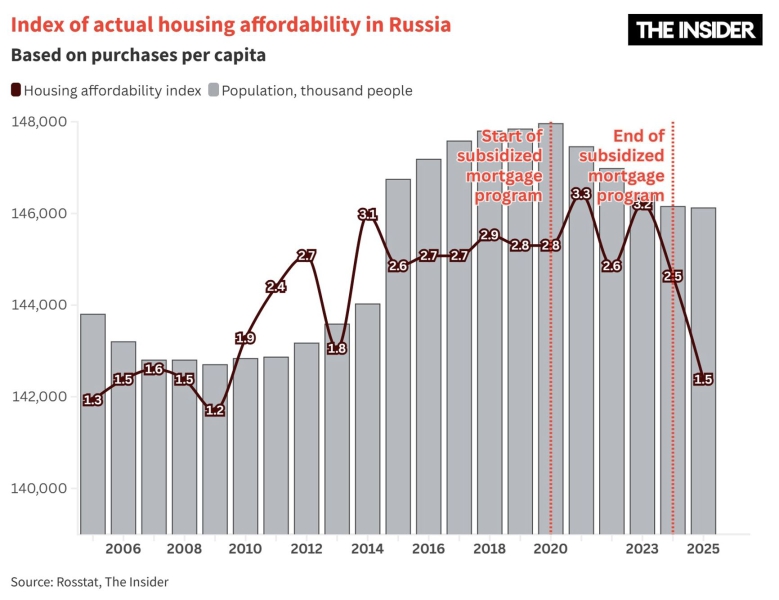

However, the price per square meter does not fully capture affordability, as it does not account for mortgage availability. If we assess actual housing accessibility by the number of transactions per capita, the index reached its historical peak in 2021, when the full-scale war had not yet begun and subsidized mortgages were already in place. After the program was scrapped and market rates surged, the index collapsed to levels last seen 20 years ago. In effect, the intensity of home purchases in the country has reverted to the 2006–2008 period, when the market was only just emerging. Despite record levels of construction, the real ability of citizens to enter into a housing transaction has been cut in half.

The same applies to food affordability. For years, Russian household spending on food has hovered around 35%, which by UN standards indicates a country that is no longer poor but not yet prosperous. According to Rosstat estimates, the cost of the minimum food basket has fluctuated, but only slightly. Between 2005 and 2024 it generally became more affordable, despite periodic price spikes for certain products. This marks an important difference between Russians and populations in Western countries: as residents of a still relatively poor country, Russians spend a large share of their income on food, so its relative decline in cost allowed a significant portion of the population to shift toward higher-quality and more expensive products. At the same time, due to historical memories of food shortages dating to the Soviet era, Russians attach far greater importance to food affordability than citizens of Western countries do.

Comparing Russia directly with the United States, France, and Germany is complicated, so here it is worth adding China, Brazil, and Poland to the comparison. Russia surpasses only Brazil in terms of wages — the average accrued salary in Russia is approaching 100,000 rubles, or about $1,300, compared with $600 in Brazil — though Brazil benefits from lower inflation (4.6% versus 5.6% in Russia). In terms of car affordability, Russia is a clear outsider, requiring about 50 average monthly salaries. As for nominal housing affordability, real estate is more within reach for Russians (four salaries per square meter) than for Americans (10 salaries), but less affordable than in Poland (3.5) and Brazil (2).

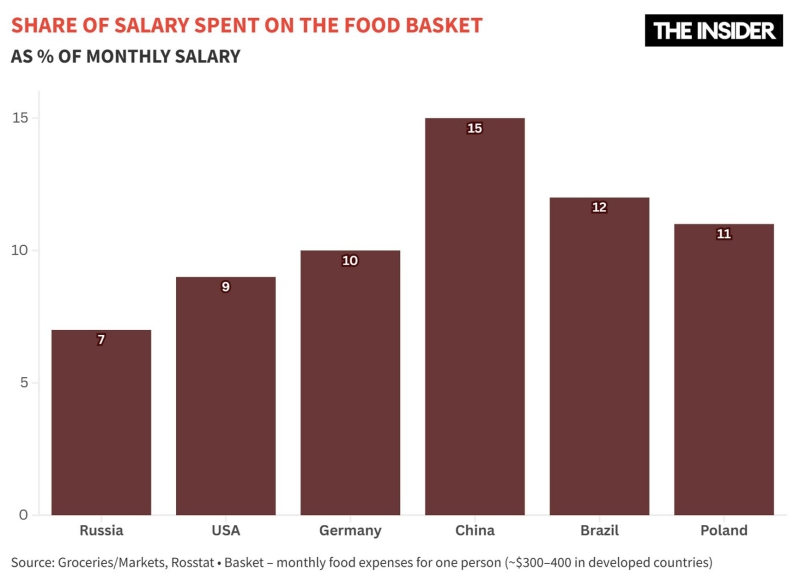

Indicators of dental affordability and the share of wages required to purchase the minimum food basket are equally contradictory. In the former case, Russia — where a filling costs $60 — falls between the United States ($100) and Germany ($80) on one side and China, Brazil, and Poland (about $50) on the other. At the same time, the minimum food basket in Russia can be purchased with the smallest share of average wages. Nevertheless, in all of the other countries listed, the share of total spending devoted to food is much lower — significantly so in the United States (6.7%).

Overall, one can conclude that in terms of basic needs Russia outperforms many countries, but lags noticeably behind in the affordability of expensive goods such as cars and ranks in the middle in housing and dentistry. The reasons are clear: the government controls the price of the minimum food basket — the so-called “borscht basket” — while leaving other products to market forces. Housing demand is stimulated through subsidized mortgage programs.

In the area of meeting basic needs, Russia outperforms many countries

Dentistry depends directly on market demand: price growth is constrained by the absence of government programs and the underdevelopment of corporate health insurance.

Cars, however, are still apparently regarded by the Russian authorities as a luxury rather than a means of transportation. Through the introduction of various fees, they address the problems of domestic automakers while replenishing the state budget. With another increase in the recycling fee set for Nov. 1, a further sharp decline in car affordability can be expected.

All this creates the image of a country that is “poor but tidy”: the authorities allow citizens to eat their fill, partially satisfy demand for housing, pay little attention to medical services not directly tied to public health and epidemiological safety, and extract additional payments from those who seek a higher quality of life through measures like the higher recycling fees on cars with engines above 160 horsepower.