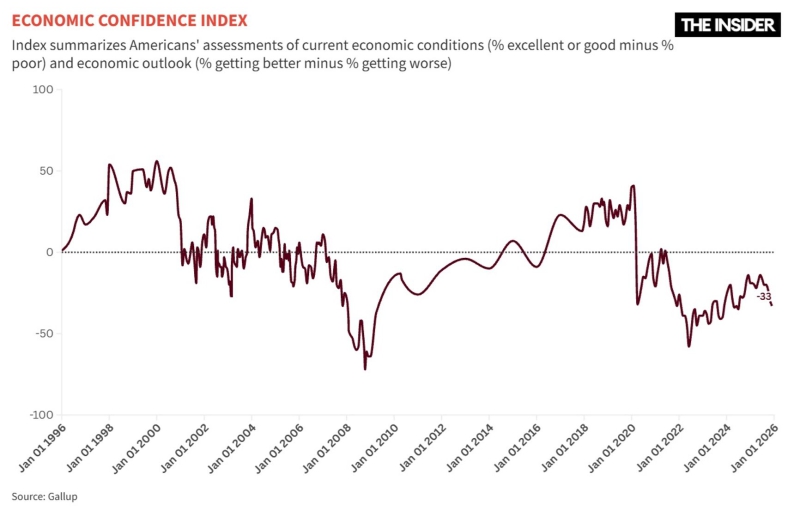

Economic issues were the main concern Trump voters cited when explaining their choice for president in the 2024 election, but today 68 percent of Americans believe the economy has only worsened over the past year. The president’s approval rating and consumer confidence indexes are falling. Donald Trump’s administration, despite promising the country a “golden age,” has fused traditional Republican policy — tax cuts and deregulation — with populist measures and muscular state intervention in the economy and trade. That mix is pushing up the deficit and the national debt, which Trump had vowed to reduce. After forcing Democrats to accept his budget agenda after a record shutdown, Trump is beginning the second year of his second term with a clash against the Federal Reserve and a more assertive squeeze on the U.S. economy. Despite the turbulence, the overall outlook remains decent, and the stock market continues to climb — albeit at a slower pace than it did under Biden. At the same time, risks persist: a potential labor shortage driven by the crackdown on migration, continuing rapid price growth largely resulting from the president’s multiple trade wars), and budgetary instability.

“The golden age of America begins right now,” Donald Trump declared in the first minutes of his second term as president. His return to the White House was helped by high inflation, which peaked under Joe Biden, and by a general sense of economic gloom that persisted despite solid statistical indicators — a vibecession. Trump promised that everything would be different under his watch, but a year later it is clear that the boom never arrived. Prices continue to climb, nominal wage growth is only barely outpacing inflation, and unemployment has edged up. A large-scale return of industrial production has not materialized either. According to forecasts from the Federal Reserve, U.S. economic growth for 2025 will come in at under 2 percent — lower than in Biden’s final year in office, when it reached 2.8 percent.

Trump was elected in no small part based on his promises to vanquish inflation on day one. The public had been shaken by a once-in-a-generation surge of 9 percent in the summer of 2022, part of a global wave triggered by lingering pandemic effects colliding with a spike in energy prices after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. By the time Trump took office, the inflation rate had fallen to just 3 percent, and in the first half of 2025, price growth did indeed slow before rising again due to Trump’s introduction of new tariffs. As a result, the average inflation rate for 2025 effectively held steady at 2.7 percent.

Trump’s statements that he would bring down food prices (they rose by 3 percent) and “crash” the cost of gasoline to below $2 per gallon also failed to make the jump from rhetoric to reality, with the current average price coming in at closer to $3. America has not become an “industrial superpower,” the goal the president purportedly attempted to achieve through protectionism. Nor have hundreds of thousands of jobs appeared in the energy sector (or elsewhere) — instead, deregulation delivered only a modest positive effect.

Prices for food and gasoline in the United States rose despite Trump’s promises

The “big, beautiful budget bill” that was pushed through the Republican-controlled Congress in July formally eased the tax burden for Americans. Thanks to the new law, the tax breaks from Trump’s first term, which were set to expire in 2025, became permanent.

Altogether, Congress distributed $4.5 trillion in tax breaks for the next ten years, mostly to wealthy households and corporations. It also cut more than $1 trillion in spending over the same period by reducing funding for health care, food assistance, and education.

These measures are nominally meant to stimulate investment and consumption, but the effect so far has been modest, and many of the provisions have hit lower-income groups hard. For example, ending subsidies for health insurance plans raised their annual cost for an average family to $27,000. And that is not the ceiling: some people now have to pay more than $40,000 a year to insure themselves against a serious illness.

Trump wrote a check for a “golden age,” but it will most likely be the children of today’s voters who will end up having to pay for it. According to estimates from the Congressional Budget Office, the Treasury will lose trillions of dollars in revenue over the long term. Despite the spending cuts, the deficit will also increase by trillions, and by mid-century the debt could exceed 200 percent of GDP.

Trump wrote a check for a “golden age,” but it will be the children of today’s voters who have to pay it

Stimulating growth through tax cuts will be short-lived, and by the late 2020s the budget burden created by the deficit will begin to weigh on economic expansion. By 2054, the current extension of the tax breaks will result in growth being almost 2 percent of GDP lower than it otherwise would have been, according to the U.S. Congressional Budget Office. By that time, of course, neither Trump nor his successors will still be in power.

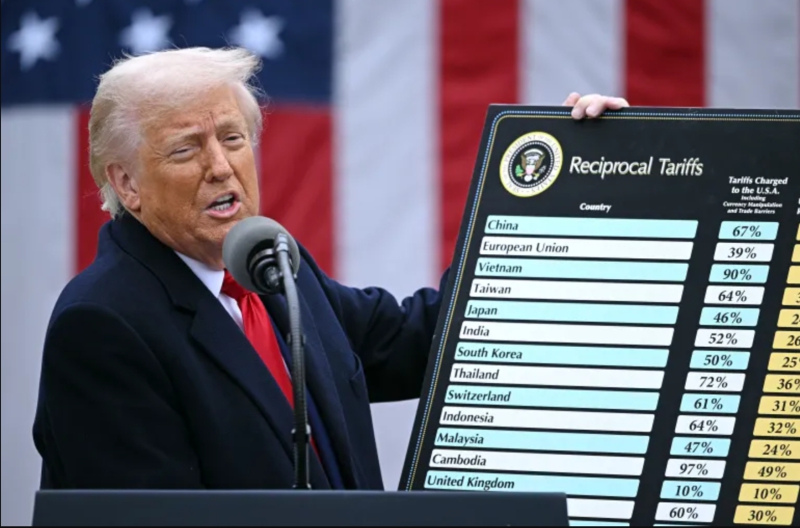

On Apr. 2, Trump torpedoed the global system of world trade by introducing a baseline tariff of 10 percent on all countries and all goods. Tariffs climbed even higher for countries that had posted the largest trade surpluses with the United States (on top of that, the calculations cited by the White House were often dubious).

The average weighted import duty rose from about 2.4 percent to 17 percent, the highest level since the failed protectionist campaign of the 1930s. Trump promised to boost federal revenue through customs duties while also stimulating domestic production and job creation. Instead, as most economists predicted, the tariffs became a de facto consumption tax on imported goods, one that ordinary Americans have to pay.

Governing through uncertainty — with trade restrictions imposed and then lifted several times a month — added global instability. The worst fears of economists, however, did not materialize: producers around the world were not ready to lose their largest market and absorbed much of the financial blow themselves. As a result, the rise in prices for foreign goods and raw materials was not explosive but gradual.

Foreign producers turned out to be unwilling to lose the largest market and absorbed much of the hit from Trump’s tariffs

By late autumn, the administration had to lower tariffs on goods that had become especially expensive, a list that included beef, coffee, tea, orange and lime juice, bananas, coconuts, pineapples, mangoes, avocados, tomatoes, spices, and certain types of fertilizer.

The White House officially explained the roll-back as being the result of the “successful completion of negotiations with Brazil, Argentina, and Ecuador.” But in practice it came immediately after Republicans performed poorly in several local and state elections in November. Exit polls showed that food prices were the top concern for voters, and the decision effectively confirmed the fact that the tariffs introduced in April had contributed to inflation.

The legality of all the increased tariffs is now being challenged in the U.S. Supreme Court. If the Court rules them unlawful, the government will have to return about $150 billion to importers. Democrats warn that investment in industrial production could shrink by half a trillion dollars. The reason — again — is the tariffs, which raised costs and increased uncertainty for American manufacturers.

Trump’s policies have also affected the workforce. Because of aggressive measures against illegal migration, the flow of migrants has almost dried up, and the outflow during the first nine months of Trump’s tenure amounted to more than 2 million people. Over half a million were deported, while the rest chose to leave voluntarily. This left many farmers on the brink of a crisis, which may affect food production. The hospitality industry has suffered as well as there is simply no one in America to replace low-paid migrant labor.

Throughout the year, Trump clashed with the American government’s system of checks and balances. The result was the longest shutdown of the federal government in history — a 43-day halt of non-essential services. More than 900,000 employees were placed on unpaid leave, and another 700,000 worked without pay (as tradition dictates, they were compensated retroactively once the shutdown ended).

The Democratic minority in the Senate blocked the Republican budget for several reasons, but primarily because of cuts to social spending and health-care subsidies. The president and Republicans refused to budge, and Democrats ultimately had to capitulate.

Even so, Trump’s approval rating slipped as a result of the budget crisis. In January 2026, his average approval stood at 43 percent, with 54 percent disapproving of the president. But a Gallup poll at the end of 2025 recorded a drop to 36 percent, the lowest figure of Trump’s second term so far.

Perhaps even more consequential were the president’s attempts to exert influence over the Federal Reserve. Trump accuses the Fed of having taken inadequate measures to combat the surge in inflation that followed the unusually high levels of government spending during the pandemic, and he continues to demand a rate cut in order to make borrowing cheaper for businesses and ordinary people, to lower the cost of servicing the national debt, to weaken the dollar, and thus to support the competitiveness of American exports.

The inevitable inflationary effects of taking such an approach would not be felt anytime soon, while the economic stimulus would appear almost immediately. Yet if the central bank’s monetary policy becomes subordinate to the fiscal needs of the executive branch, confidence among businesses and households could begin to fall, and even a hint that the Fed is losing its independence would translate into to market volatility.

In the spring of 2025, as inflation receded, the Fed began cautiously lowering rates, but that did not satisfy Trump. He called Jerome Powell — whom he himself had appointed Fed chair in 2018 — a “stubborn jackass” and a “moron,” demanding far more radical action.

Powell at first tried to steer clear of a direct confrontation, merely warning about the negative consequences of the Fed losing its independence. But in January 2026 the Fed chair became the latest target of a Trump political smear campaign. The Justice Department launched a criminal investigation, officially on the suspicion that Powell had abused his authority in connection with the renovation of the Fed’s headquarters.

Powell described the accusations as an attempt to punish the Federal Reserve for its independence and for refusing to comply with the president’s demands. Democrats and even some Republicans condemned the persecution of Powell as an effort to bend monetary policy to political whims.

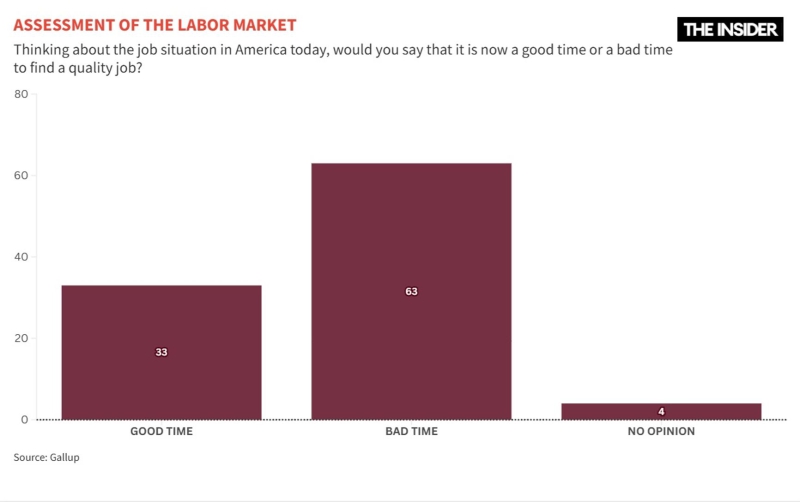

Trump’s key promise to voters — to create hundreds of thousands of jobs — also remains unfulfilled. Unemployment has risen to 4.4 percent, a four-year high, with 63 percent of Americans telling pollsters that this is a bad time to look for a good job, a level not seen since the pandemic.

Roughly 70 percent of voters said in a December AP/NORC poll that they view the state of the economy negatively. Trump is trying to offer new promises, sometimes pledging $2,000 per person in direct payouts funded by import duties, other times vowing to cap credit-card interest rates. But both measures could backfire on voters: handing out money would only fuel inflation, while capping rates would reduce access to credit cards for people with low credit scores, since issuing banks would no longer be able to adequately cover their risks.

Most Americans (70 percent) view the state of the U.S. economy negatively

Perceptions of the economy are shaped less by abstract GDP figures than by daily expenses for housing, food, healthcare, and borrowing costs. Inflation, though nowhere near the levels of three years ago, remains high by American standards, and expensive loans, especially mortgages, reinforce the sense that living standards are slipping.

On the other hand, while the first year of Trump’s second term has not been a prosperous one for the economy, neither has the collapse predicted by some economists materialized. What has changed is the underlying model of economic policy — from a “liberal world order” to “mercantilism 2.0.”

Growth in the United States is still driven by the inertia of consumer demand and private investment, not by Trump’s favored tools of protectionism, tariff wars, or administrative pressure. At the same time, the negative effects of his policies are gradually accumulating in the form of labor shortages, budget imbalances, growing uncertainty for businesses, and eroding trust in institutions.

The economy is withstanding the experiment for now, but its resilience depends increasingly less on fundamentals and ever more on the government’s ability to simply stop inflicting harm before it is too late. The second year of the second Trump presidency will test not the pace of growth, but how far those in power are willing to go when it comes to politicizing economic decisions. A crisis may still be a long way off, but the moment the market stops believing that the old economic rules remain in place, the downturn could be sudden.