Photo: Alexander Ryumin / TASS

The Russian economy moved into an unmistakable period of decline in 2025: businesses lost money, the treasury remained solvent only by raising taxes, and inflation was brought under control only thanks to high central bank interest rates. At the same time, the year resolved a few key contradictions. Unlike in 2024, when The Insider described Russian inflation as “embarrassingly high for a country with a strong budget,” 2025 saw a noticeably weaker budget, but lower inflation. Other major economic developments included an obvious downturn in the civilian sector and the sharpest tax increases in years. Together, these four facts form a coherent picture: the Kremlin fears inflation above all else, while other risks — declining production, bankruptcies, payment arrears, the impoverishment of the population, the disloyalty of the elite, the degradation of infrastructure, and even underfunding of the military and social systems — competed for runner-up in a contest with no winners.

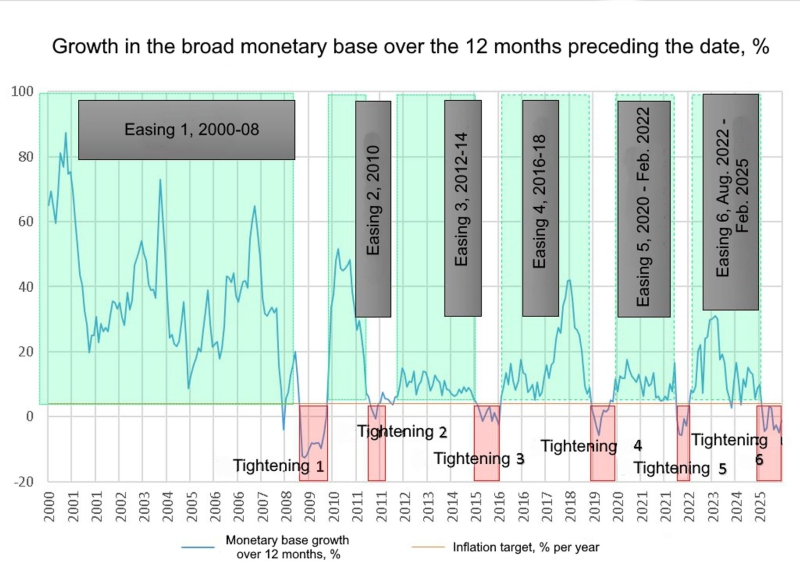

“According to weekly data, annual inflation has already fallen below 6%. By the end of the year, price growth will be at its lowest level in the past five years,” Central Bank Governor Elvira Nabiullina said on Dec. 19 at a year-end news conference focusing on interest rates. Given that official inflation was a staggering 9.52% at the end of 2024, the fall to 6% can be considered the financial authorities’ main success of the year. Russian monetary policy has finally become tight. This is not only about the key rate, raised a year ago to a historic high, but also about the fact that the Bank of Russia has stopped expanding the money supply.

Strict monetary policy can be described as such only when the amount of money in the economy does not grow (or grows only slightly, in line with liquid foreign exchange reserves). But Russia’s international reserves can no longer be considered liquid: even the portion that is not frozen is difficult to convert into freely usable currencies. As a result, changes in the money supply are the most telling indicator.

The money supply has two components. First is the monetary base, roughly two-thirds of which is made up of cash in circulation and one-third of commercial bank funds held at the central bank. The authorities set the size of this base directly. Second is “bank money,” whose volume is also determined by the central bank, albeit indirectly (through regulation of commercial banks).

The amount of bank money is almost always several times larger than the base. However, bank money is of course highly sensitive to changes in the base. It can rise sharply when the base is increased slightly and fall just as sharply when the base is reduced. The multiplier measuring this reaction varies over time, rising during booms and under other conditions leading to cheap money.

To assess the strictness of monetary policy, it is useful to look at how the base has changed over the past 12 months. The inflation target set by the central bank is 4%, and it would be strange to call a policy “tight” if the regulator is expanding the monetary base at a faster pace than that target. In this case, if the base exceeds its year-on-year level by more than 4%, the central bank’s policy is loose. Only when base growth over the course of a year is below 4% can policy logically be called tight.

Applying this criterion shows that Russia’s monetary policy became tight in March 2025 and has remained so for nine consecutive months. By contrast, in 2024 short periods of tightening were limited to February and June, while in 2022, serious attempts to curb inflation by limiting money supply growth were seen from March to September 2022. At that time, the Bank of Russia managed to slow price growth for six months, but then loosened again in an effort to “stimulate the economy.” That phase lasted nearly two and a half years and led to what became known as overheating.

Also known as the monetary aggregate M2, this is the total of cash in circulation outside banks and ruble-denominated deposits held by companies and households.

Cash in circulation, including funds held in bank vaults, and funds in mandatory reserve accounts deposited by credit institutions with the Bank of Russia.

The monetary base in the broad definition includes cash (both in bank vaults and ATMs), funds in correspondent accounts, funds in banks’ mandatory reserve accounts, banks’ deposits with the central bank, and banks’ investments in central bank bonds.

Indicators required for joining the eurozone. They show the viability of the financial system, the price level, and the stability of the exchange rate.

Coal, natural gas, sausages, canned goods, fish, vegetables, sunflower oil, flour, cereals, sugar, confectionery, beer, wool, leather, canvas, footwear, timber, plywood, particleboard, wallpaper, coke, plastics, polymers, varnishes and paints, glass, ceramic tiles, bricks, cement, concrete, cast iron, steel, rolled metal, pipes, iron parts, aluminum and aluminum products, all types of engines and batteries, agricultural and household appliances, elevators, passenger cars and trucks, buses, trailers, vehicle bodies, electricity.

Before the war, strict policy was similarly rare: from March to October 2019, from March 2015 to early 2016, in the summer of 2011, and from December 2008 to November 2009. That was it. At all other times, policy was loose, with base growth even reaching 40% a year.

As of Jan. 1, 2025, the monetary base in the broad definition stood at 27.96 trillion rubles; by Dec. 1 it had slipped slightly to 27.85 trillion. It is no longer growing, a clear sign that the central bank is seriously trying to curb inflation.

However, the picture looks different when examining the broader money supply. The most recent figure, as of Nov. 1, was 123 trillion rubles — 5% higher than at the start of 2025 and 13% higher than a year earlier. Notably, of the 5% increase since January, 1.5 percentage points came in the final month.

The central bank itself has stopped inflating the money supply, but it is nevertheless allowing commercial banks to do so. The base is not growing, but “bank” or “credit” money continues to expand (albeit more slowly than before). The multiplier — the ratio of M2 to the monetary base — rose from 4.19 to 4.58. Credit continues to swell, which can push up demand for many goods — and therefore prices. As of Nov. 1, household deposits in Russian banks exceeded 60 trillion rubles for the first time. Over the past year they grew by 20%, and since Nov. 1, 2022 they have doubled.

Also known as the monetary aggregate M2, this is the total of cash in circulation outside banks and ruble-denominated deposits held by companies and households.

Cash in circulation, including funds held in bank vaults, and funds in mandatory reserve accounts deposited by credit institutions with the Bank of Russia.

The monetary base in the broad definition includes cash (both in bank vaults and ATMs), funds in correspondent accounts, funds in banks’ mandatory reserve accounts, banks’ deposits with the central bank, and banks’ investments in central bank bonds.

Indicators required for joining the eurozone. They show the viability of the financial system, the price level, and the stability of the exchange rate.

Coal, natural gas, sausages, canned goods, fish, vegetables, sunflower oil, flour, cereals, sugar, confectionery, beer, wool, leather, canvas, footwear, timber, plywood, particleboard, wallpaper, coke, plastics, polymers, varnishes and paints, glass, ceramic tiles, bricks, cement, concrete, cast iron, steel, rolled metal, pipes, iron parts, aluminum and aluminum products, all types of engines and batteries, agricultural and household appliances, elevators, passenger cars and trucks, buses, trailers, vehicle bodies, electricity.

Credit continues to swell, which can push up demand for many goods — and therefore prices.

At the same time, debt is rising, especially in the corporate sector. Russian companies owe banks 84 trillion rubles), an 11% increase over the past year (including 6.3% in the last four months alone). Three years ago, corporate debt stood at just 48 trillion rubles.

Thus, while the Bank of Russia has stopped directly creating money out of thin air, the commercial banks operating under its oversight continue to do so actively. Anti-inflation policy remains moderate and cautious. Given that on Dec. 19 the central bank once again cut the key rate — down to 16% — the decrease in inflation may prove to have been a temporary pleasant surprise.

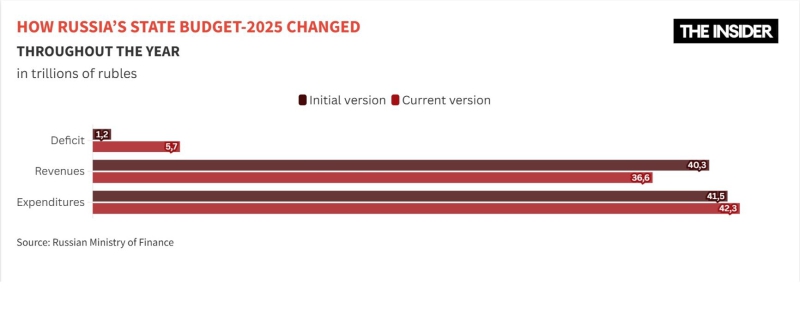

Fiscal policy, by contrast, loosened, with the federal budget deficit growing sharply, mainly due to tax shortfalls.

Also known as the monetary aggregate M2, this is the total of cash in circulation outside banks and ruble-denominated deposits held by companies and households.

Cash in circulation, including funds held in bank vaults, and funds in mandatory reserve accounts deposited by credit institutions with the Bank of Russia.

The monetary base in the broad definition includes cash (both in bank vaults and ATMs), funds in correspondent accounts, funds in banks’ mandatory reserve accounts, banks’ deposits with the central bank, and banks’ investments in central bank bonds.

Indicators required for joining the eurozone. They show the viability of the financial system, the price level, and the stability of the exchange rate.

Coal, natural gas, sausages, canned goods, fish, vegetables, sunflower oil, flour, cereals, sugar, confectionery, beer, wool, leather, canvas, footwear, timber, plywood, particleboard, wallpaper, coke, plastics, polymers, varnishes and paints, glass, ceramic tiles, bricks, cement, concrete, cast iron, steel, rolled metal, pipes, iron parts, aluminum and aluminum products, all types of engines and batteries, agricultural and household appliances, elevators, passenger cars and trucks, buses, trailers, vehicle bodies, electricity.

Of the 4.5 trillion ruble increase in the budget “hole,” only 0.9 trillion rubles came from higher spending, while 3.7 trillion rubles reflected lost revenues. When the 2025 budget was adopted, revenues were expected to rise by 11.6% year on year, but after 11 months, they were up just 0.7%.

Oil and gas revenues were initially projected at 10.9 trillion rubles but were later revised down to 8.6 trillion, and in reality, only 8 trillion rubles were collected from January through November, 22.4% less than a year earlier. Even if December collections closed the gap with the revised plan, they would still be 24% below actual 2024 revenues.

The sharpest shortfall came from oil and gas. Last year, the export price of Russia’s Urals crude was forecast at $69.70 per barrel, but the actual average came in at $58 — 17% below projections.

So why did oil and gas revenues fall by an even larger 24%? There was a slight drop in output — by 1%, in line with OPEC+ limits early in the year — but more important was the performance of the ruble, which strengthened 45% against the dollar. The currency gained as demand for foreign exchange fell — partly because of sanctions, and partly because of the central bank’s high interest rate.

Also known as the monetary aggregate M2, this is the total of cash in circulation outside banks and ruble-denominated deposits held by companies and households.

Cash in circulation, including funds held in bank vaults, and funds in mandatory reserve accounts deposited by credit institutions with the Bank of Russia.

The monetary base in the broad definition includes cash (both in bank vaults and ATMs), funds in correspondent accounts, funds in banks’ mandatory reserve accounts, banks’ deposits with the central bank, and banks’ investments in central bank bonds.

Indicators required for joining the eurozone. They show the viability of the financial system, the price level, and the stability of the exchange rate.

Coal, natural gas, sausages, canned goods, fish, vegetables, sunflower oil, flour, cereals, sugar, confectionery, beer, wool, leather, canvas, footwear, timber, plywood, particleboard, wallpaper, coke, plastics, polymers, varnishes and paints, glass, ceramic tiles, bricks, cement, concrete, cast iron, steel, rolled metal, pipes, iron parts, aluminum and aluminum products, all types of engines and batteries, agricultural and household appliances, elevators, passenger cars and trucks, buses, trailers, vehicle bodies, electricity.

A far bigger factor in the fall of Russia’s oil and gas revenues was the ruble, which strengthened 45% against the dollar over the course of the past year.

Other revenues were expected to reach 29.4 trillion rubles but came in lower, as only 24.9 trillion rubles were collected from January through November. For the full year, the Finance Ministry expects 28.4 trillion rubles (which is still 11% more than last year). Notably, revenues linked to domestic production rose, while those tied to imports fell.

The most striking growth came from personal income tax, whose receipts more than doubled. Starting from Jan. 1, 2025, Russia raised income tax rates, replacing the prior two-bracket system — set at 13% and 15% — with five brackets ranging from 13% up to 22%. Taxes collected at the 13% rate go to regional and local budgets, while anything above that goes to the federal budget, and regional income tax revenues also rose — by 13.9% from January through September. In other words, trends in household income remain positive.

The situation is worse for companies. Corporate profit tax revenues to the federal budget jumped by 75%, while regional revenues fell by 2.5%. The explanation is straightforward. In 2024, the overall profit tax rate was 20%, with 3% going to the federal center and 17% to regions. However, in 2025 the rate was raised to 25%, with the federal government taking 8% and regions still receiving 17%. In short, the tax hike benefited only the Kremlin, while companies and regional budgets lost out (with the latter receiving the same share from a shrinking pool of taxable profits).

Also known as the monetary aggregate M2, this is the total of cash in circulation outside banks and ruble-denominated deposits held by companies and households.

Cash in circulation, including funds held in bank vaults, and funds in mandatory reserve accounts deposited by credit institutions with the Bank of Russia.

The monetary base in the broad definition includes cash (both in bank vaults and ATMs), funds in correspondent accounts, funds in banks’ mandatory reserve accounts, banks’ deposits with the central bank, and banks’ investments in central bank bonds.

Indicators required for joining the eurozone. They show the viability of the financial system, the price level, and the stability of the exchange rate.

Coal, natural gas, sausages, canned goods, fish, vegetables, sunflower oil, flour, cereals, sugar, confectionery, beer, wool, leather, canvas, footwear, timber, plywood, particleboard, wallpaper, coke, plastics, polymers, varnishes and paints, glass, ceramic tiles, bricks, cement, concrete, cast iron, steel, rolled metal, pipes, iron parts, aluminum and aluminum products, all types of engines and batteries, agricultural and household appliances, elevators, passenger cars and trucks, buses, trailers, vehicle bodies, electricity.

The tax hike benefited only the Kremlin, while companies and regional budgets lost out.

Federal budget revenues generated from excise taxes on domestically produced goods rose by 27% over the year, also the result of higher rates. Excise taxes were increased on cigarettes and tobacco products, alcohol, and sugar-sweetened beverages. In addition, excise taxes were introduced on alcohol-containing medicines, nicotine raw materials, tobacco-free nicotine mixtures, and natural gas used to produce ammonia.

Finally, revenues from value-added tax (VAT) on domestically produced goods and services rose by 17% and, for the first time in history, exceeded revenues from oil and gas. As in the previously cited cases, the growth rate of tax collections outpaced the growth of the tax base. The state’s take from VAT rose faster than value added itself. Here, too, the explanation is the same — a higher relative tax burden.

From Jan. 1, 2025, the simplified tax regime that allowed companies with annual revenue above 60 million rubles to avoid paying VAT was effectively abolished, and starting in 2026, the main VAT rate will be raised further — from 20% to 22%, with the circle of taxpayers also set to be expanded. This may allow the government to continue increasing collections, but only at the cost of rapidly impoverishing those who pay the taxes.

Meanwhile, revenues linked to imports are moving in the opposite direction. Over the first 11 months of 2025, VAT receipts on imported goods fell by 14%, revenue from import duties dropped 15%, and excise taxes on imports declined by 22%. This is a fairly sharp fall. Overall import dynamics this year were also negative, but not nearly that negative: imports into Russia, measured in dollars, fell 2.4%, while exports declined by a moderate 4.3%.

As for the final tally on federal spending and the budget deficit, conclusive calculations must wait until December’s results become available. Still, practice shows that in the closing month of the year, spending is significantly higher — sometimes several times higher — than in any other month. For example, in 2023 December spending was 2.32 times higher than the average monthly level from January through November, and in 2024 it was 2.54 times higher. Revenues do not show such dynamics, meaning the budget deficit typically surges sharply at this time. If the trend is extrapolated to December 2025, total annual spending could reach anywhere from 45 trillion to 45.8 trillion rubles (although the Finance Ministry insists it will come in at a mere 42.8 trillion).

Throughout the year, Finance Minister Anton Siluanov and his colleagues repeatedly said that the unusually large deficits seen early on would eventually be offset by a smaller-than-usual December spending surge. And indeed, the pace of spending growth slowed as 2025 progressed: in the first quarter it exceeded last year’s level by 24.5%, over the first half of the year by 20.2%, and over nine months by 19.5%. At the same time, however, the Finance Ministry’s own projected deficit grew — from 0.5% of GDP at the start of the year to 2.6% of GDP now. If the budget hole increases fivefold in just a few months, then further forecasts from the financial authorities should be treated skeptically.

Also known as the monetary aggregate M2, this is the total of cash in circulation outside banks and ruble-denominated deposits held by companies and households.

Cash in circulation, including funds held in bank vaults, and funds in mandatory reserve accounts deposited by credit institutions with the Bank of Russia.

The monetary base in the broad definition includes cash (both in bank vaults and ATMs), funds in correspondent accounts, funds in banks’ mandatory reserve accounts, banks’ deposits with the central bank, and banks’ investments in central bank bonds.

Indicators required for joining the eurozone. They show the viability of the financial system, the price level, and the stability of the exchange rate.

Coal, natural gas, sausages, canned goods, fish, vegetables, sunflower oil, flour, cereals, sugar, confectionery, beer, wool, leather, canvas, footwear, timber, plywood, particleboard, wallpaper, coke, plastics, polymers, varnishes and paints, glass, ceramic tiles, bricks, cement, concrete, cast iron, steel, rolled metal, pipes, iron parts, aluminum and aluminum products, all types of engines and batteries, agricultural and household appliances, elevators, passenger cars and trucks, buses, trailers, vehicle bodies, electricity.

The final size of Russia’s budget deficit will only be known in early 2026.

The moment of truth is now approaching. If the Finance Ministry keeps its word, the budget deficit will look relatively unremarkable. The Maastricht criteria used as a standard in the European Union (even if they are often violated by many member states) recommend keeping the deficit below 3% of GDP. Still, in 2025 only three G7 countries remained within those limits: Canada (1.9%), Japan (2.85%), and Germany (2.95%). Italy’s deficit is 3.3% of GDP, Britain’s 4.4%, France’s 5.5% and the United States’ 6.5%. Even a Russian deficit of 2.6% would not look alarming against that backdrop. Still, the concern is that if the usual December spending spike turns out to have occurred, the deficit could reach 8 trillion to 9 trillion rubles, or 3.6% to 4% of GDP.

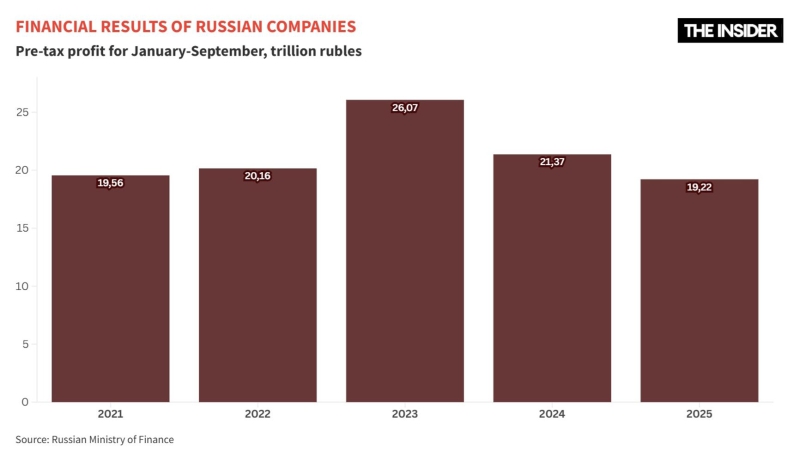

Even if the budget can be brought back under control, that would only represent a short-term achievement. Balancing the books by raising taxes while the economy is contracting is a dead end — and that is exactly the road Russia is on now. The combined profits of Russian companies, as measured by the country’s state statistics agency Rosstat, have been falling for a second consecutive year and have reached their lowest level in five years.

Also known as the monetary aggregate M2, this is the total of cash in circulation outside banks and ruble-denominated deposits held by companies and households.

Cash in circulation, including funds held in bank vaults, and funds in mandatory reserve accounts deposited by credit institutions with the Bank of Russia.

The monetary base in the broad definition includes cash (both in bank vaults and ATMs), funds in correspondent accounts, funds in banks’ mandatory reserve accounts, banks’ deposits with the central bank, and banks’ investments in central bank bonds.

Indicators required for joining the eurozone. They show the viability of the financial system, the price level, and the stability of the exchange rate.

Coal, natural gas, sausages, canned goods, fish, vegetables, sunflower oil, flour, cereals, sugar, confectionery, beer, wool, leather, canvas, footwear, timber, plywood, particleboard, wallpaper, coke, plastics, polymers, varnishes and paints, glass, ceramic tiles, bricks, cement, concrete, cast iron, steel, rolled metal, pipes, iron parts, aluminum and aluminum products, all types of engines and batteries, agricultural and household appliances, elevators, passenger cars and trucks, buses, trailers, vehicle bodies, electricity.

The final financial result before taxes for January through October amounted to just 90% of last year’s level, which itself was only 82% of the 2023 figure. The situation is especially dire in coal mining: production has been weak for a second year in a row, and total losses quadrupled, reaching 328 billion rubles over the first 10 months of the year. Forestry, logging, and wood processing, which were profitable in 2024, are also now in the red. A number of industries remain in surplus, but their profits have fallen by half or more — these include oil and natural gas extraction, coke and petroleum products manufacturing, and paper production. In the auto industry and rail freight transport sector, profits fell by upwards of 75%.

In building construction, profits rose by a factor of 1.5, but in civil engineering they fell 35%. Overall profits in trade are just 77% of last year’s level. Wholesale trade is declining, retail trade posted 6% growth, while car dealers saw profits crater. Transport shows mixed dynamics: road freight lost nearly half its profits, rail freight three-quarters, and water transport 27%. At the same time, pipelines and intercity passenger transport maintained last year’s levels, and air transport tripled its profits.

Against the backdrop of a general downturn in Russian business, some sectors can boast profit growth. These include IT, air transportation, fishing, research and development, and financial and insurance services. In all of these segments, results in 2025 at least doubled compared with the same period a year earlier.

The success of IT companies is easily explained by the global growth of the sector and the low activity of Western competitors in the Russian market. Government contracts, meanwhile, play an important role in driving in R&D — even if it is not of the sort that actually improves people’s lives.

In absolute terms, financiers and insurers gained the most. Their combined financial result rose by more than 1 trillion rubles. Almost half of that growth was driven by an increase in net interest income at commercial banks — up 425 billion rubles over the first nine months of the year. The period of high interest rates meant banks’ interest income rose from 16.4 trillion to 22.3 trillion rubles, while expenses increased less sharply, from 11.4 trillion to 17 trillion. Interest charged on loans rose faster than interest paid on deposits, and high rates also increased the value of government bonds held in bank portfolios.

Also known as the monetary aggregate M2, this is the total of cash in circulation outside banks and ruble-denominated deposits held by companies and households.

Cash in circulation, including funds held in bank vaults, and funds in mandatory reserve accounts deposited by credit institutions with the Bank of Russia.

The monetary base in the broad definition includes cash (both in bank vaults and ATMs), funds in correspondent accounts, funds in banks’ mandatory reserve accounts, banks’ deposits with the central bank, and banks’ investments in central bank bonds.

Indicators required for joining the eurozone. They show the viability of the financial system, the price level, and the stability of the exchange rate.

Coal, natural gas, sausages, canned goods, fish, vegetables, sunflower oil, flour, cereals, sugar, confectionery, beer, wool, leather, canvas, footwear, timber, plywood, particleboard, wallpaper, coke, plastics, polymers, varnishes and paints, glass, ceramic tiles, bricks, cement, concrete, cast iron, steel, rolled metal, pipes, iron parts, aluminum and aluminum products, all types of engines and batteries, agricultural and household appliances, elevators, passenger cars and trucks, buses, trailers, vehicle bodies, electricity.

In absolute terms, financiers and insurers gained the most.

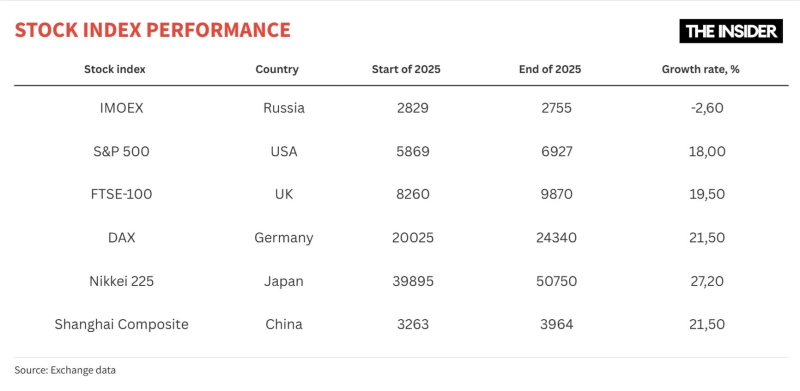

Russian stocks, however, have fallen since the start of 2025, though not as sharply as in the disastrous 2024. For a broader comparison, however, while the Russian stock market slipped 2.6%, markets in the United States, Britain, Germany, Japan, and China rose between 18% and 27%.

Also known as the monetary aggregate M2, this is the total of cash in circulation outside banks and ruble-denominated deposits held by companies and households.

Cash in circulation, including funds held in bank vaults, and funds in mandatory reserve accounts deposited by credit institutions with the Bank of Russia.

The monetary base in the broad definition includes cash (both in bank vaults and ATMs), funds in correspondent accounts, funds in banks’ mandatory reserve accounts, banks’ deposits with the central bank, and banks’ investments in central bank bonds.

Indicators required for joining the eurozone. They show the viability of the financial system, the price level, and the stability of the exchange rate.

Coal, natural gas, sausages, canned goods, fish, vegetables, sunflower oil, flour, cereals, sugar, confectionery, beer, wool, leather, canvas, footwear, timber, plywood, particleboard, wallpaper, coke, plastics, polymers, varnishes and paints, glass, ceramic tiles, bricks, cement, concrete, cast iron, steel, rolled metal, pipes, iron parts, aluminum and aluminum products, all types of engines and batteries, agricultural and household appliances, elevators, passenger cars and trucks, buses, trailers, vehicle bodies, electricity.

In value terms, Rosstat assesses production across 24 manufacturing industries and records declines in 17 of them. The steepest drops were recorded in automobile manufacturing (down 23%), leather production (14%), and printing (13%). Growth was recorded in only seven industries, mainly military-related: fabricated metal products excluding machinery and equipment, other transport equipment, repair and installation of machinery and equipment, and computers, electronic and optical products. There was also modest growth in tobacco and textile manufacturing, and a more noticeable increase in pharmaceuticals and materials used for medical and veterinary purposes.

It is clear that military and medical purchases are largely made by the state, which diverts resources from other sectors. This picture confirms that almost all donor industries are shrinking, meaning that the government’s priority sectors will continue to be subsidized at the expense of the same donors.

Still, the category of taxpayer suffering the most is entrepreneurs. As profits fall and the stock market sags, taxes are being raised primarily on businesses (even if they hit everyone else indirectly). As a consequence, the structure of loans issued by Russian banks shows that legal entities are increasingly borrowing from individuals.

Also known as the monetary aggregate M2, this is the total of cash in circulation outside banks and ruble-denominated deposits held by companies and households.

Cash in circulation, including funds held in bank vaults, and funds in mandatory reserve accounts deposited by credit institutions with the Bank of Russia.

The monetary base in the broad definition includes cash (both in bank vaults and ATMs), funds in correspondent accounts, funds in banks’ mandatory reserve accounts, banks’ deposits with the central bank, and banks’ investments in central bank bonds.

Indicators required for joining the eurozone. They show the viability of the financial system, the price level, and the stability of the exchange rate.

Coal, natural gas, sausages, canned goods, fish, vegetables, sunflower oil, flour, cereals, sugar, confectionery, beer, wool, leather, canvas, footwear, timber, plywood, particleboard, wallpaper, coke, plastics, polymers, varnishes and paints, glass, ceramic tiles, bricks, cement, concrete, cast iron, steel, rolled metal, pipes, iron parts, aluminum and aluminum products, all types of engines and batteries, agricultural and household appliances, elevators, passenger cars and trucks, buses, trailers, vehicle bodies, electricity.

The category of taxpayer suffering the most is entrepreneurs.

“Everything happening in the Russian economy is easily described by an introductory macroeconomics textbook explaining the business cycle driven by government spending,” economist Tatiana Mikhailova, a visiting assistant professor of economics at the University of Pennsylvania, told The Insider Live. “The state spends money on the military or, say, infrastructure. That money spreads through the economy via the multiplier, ends up in people’s pockets, and stimulates demand for goods and services. Inflation then starts to rise, especially when, as in Russia, government spending does not go toward anything productive that would help the economy grow. Money loses value, consumption becomes harder, real income growth stops, the stimulus runs out, inflation falls, and the economy begins to retreat. In Russia, this stage has lasted since late 2024. That means the economy has not grown in real terms for a year. Some sectors have begun to decline, and consumption is starting to stagnate.”

Fear of inflation and a reluctance to explain to society why it has been forced to make such large and seemingly pointless sacrifices have combined to push the regime toward an austerity policy for 2026 — raising taxes and cutting spending — including on the military, if official budget figures for next year are to be believed.

But this belt-tightening has come too late. The burden placed on the economy’s net donors — the people and enterprises forced to subsidize everyone else — has already become excessive. Under its weight, the productive sector has begun to contract, causing tax revenues levied on profits, turnover, value added, and existing assets to fall.

The Russian economy that enters 2026 is like a group of people standing on a slowly melting ice floe. The support structure is melting on its own, but the unfortunate polar explorers are also constantly breaking off ever-larger chunks and, out of spite, throwing them at equally desperate people on a neighboring floe. It is hard even to imagine the effort and sacrifices that will be required to return to normality once the leadership on the “Russia” ice floe inevitably changes.

Also known as the monetary aggregate M2, this is the total of cash in circulation outside banks and ruble-denominated deposits held by companies and households.

Cash in circulation, including funds held in bank vaults, and funds in mandatory reserve accounts deposited by credit institutions with the Bank of Russia.

The monetary base in the broad definition includes cash (both in bank vaults and ATMs), funds in correspondent accounts, funds in banks’ mandatory reserve accounts, banks’ deposits with the central bank, and banks’ investments in central bank bonds.

Indicators required for joining the eurozone. They show the viability of the financial system, the price level, and the stability of the exchange rate.

Coal, natural gas, sausages, canned goods, fish, vegetables, sunflower oil, flour, cereals, sugar, confectionery, beer, wool, leather, canvas, footwear, timber, plywood, particleboard, wallpaper, coke, plastics, polymers, varnishes and paints, glass, ceramic tiles, bricks, cement, concrete, cast iron, steel, rolled metal, pipes, iron parts, aluminum and aluminum products, all types of engines and batteries, agricultural and household appliances, elevators, passenger cars and trucks, buses, trailers, vehicle bodies, electricity.