Ukrainian drone attacks have begun prioritizing a new target: Russian fuel infrastructure facilities. Since the beginning of the year, twelve refineries have been hit, and the damage is far from harmless. If three critical refineries in southern Russia are hit at the same time, there could be serious disruptions in fuel supplies to the front lines.

The international sanctions regime plays a role in this process. Although the restrictions have not yet had a serious effect on Russian oil production or refining capacity, Moscow’s limited access to Western-made components has rendered the repair process for damaged refineries more difficult. Yes, the country is still completely self-sufficient in energy, with more than half of all domestic production remaining in Russia for internal consumption and half being exported (mainly diesel and fuel oil). But accidents and explosions, unlike sanctions, can cause lengthy refinery shutdowns, jeopardizing Russia’s prized self-sufficiency, if only in the short term.

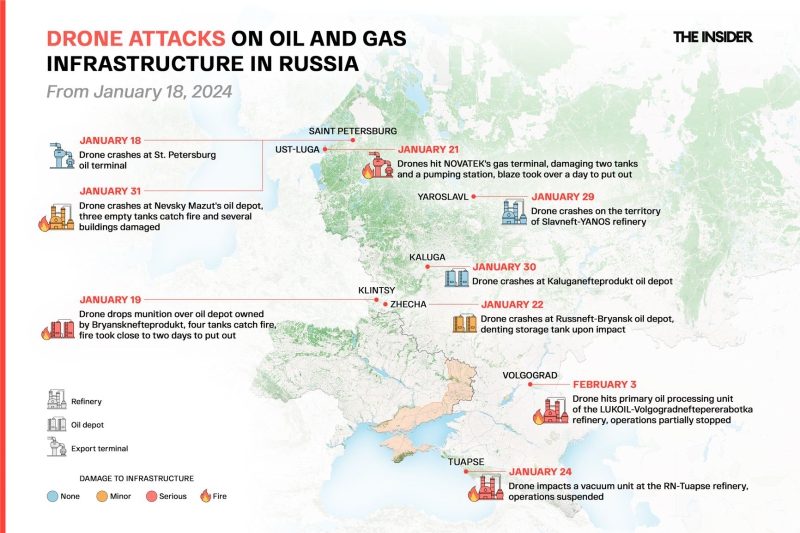

Since the start of 2024, Ukrainian drones have struck twelve Russian refineries, but so far there have been few truly destructive hits. The first serious impact occurred at one of Russia's largest oil refineries — Rosneft's facility in the southern city of Tuapse. According to The Insider's source in the city administration, a vacuum column at the refinery caught fire as a result of the strike. As per Reuters, the facility’s operations have been halted until March.

The vacuum unit is the main target in a refinery of this kind, as liquid petroleum products are difficult to ignite, even with explosives dropped from drones. Refineries are very secure and well-protected structures, built with the expectation that they could be attacked, as Carnegie expert Sergei Vakulenko has explained. However, if a strike manages to score a direct hit on an oil-gas separation column, “you can cause an explosion and a big fire.”

The difference between a strike on the vacuum column and a strike on a less vulnerable section of a refinery can be measured in months. On the morning of February 3, a drone crashed into a primary oil refining unit at the Lukoil refinery in Volgograd, the largest producer and supplier of petroleum in the country’s Southern Federal District. The refinery had been upgraded in 2022, and the technology unit installed included a vacuum column. However, the drone struck a pipeline, and not the unit itself. As a result, Lukoil's statement on the same day noted — credibly — that the refinery was operating normally.

Russia responded by attacking the Kremenchuk refinery in central Ukraine with two Iskander missiles. Russian missiles had first struck Ukraine's largest oil refinery (designed to produce 18.6 million tons per year) in April 2022. At the time, the Ukrainian regional administration claimed the facility would be offline until the end of the year. In February 2023, however, former Verkhovna Rada deputy Oleg Tsaryov said that, according to his data, the refinery was never fully closed.

Weeks earlier, on January 15, there had been an accident at Lukoil-Nizhegorodnefteorgsintez in the Russian city of Kstovo, located roughly 400 kilometers east of Moscow and just under 1000 from the Ukrainian border. The scarcely pronounceable refinery is is Lukoil's largest and the fourth largest in Russia overall. Although a catalytic cracking unit appeared to have failed there, it remains unclear what the overall impact of the strike has been. On January 31, several drones were shot down near the refinery.

Update: Since this article was published on The Insider’s Russian version on February 7, another drone struck an oil refinery in Ilsk, Krasnodar Krai (February 9). The Afipsky oil refinery in Krasnodar Krai was also attacked on the same day, with a drone crashing on the premises at around 04:00 a.m, as per an Ukrainska Pravda report citing the Astra and Shot Telegram channels. A third drone hit an oil refinery in Stalnoy Kon in Oryol Oblast on the same day, exploding after impact. No damage or casualties have yet been confirmed.

These strikes are not reflected in the infographic above.

Ukraine is striking oil refineries because that’s where the oil is (or, at least, that’s where crude oil is rendered into the kind of fuel that can actually be used to power the Russian war machine). As Ukrainian military expert Leonid Dmitriev explains the logic, “In the case of strikes, sabotage and 'sudden accidents' at Russian refineries, such as Lukoil's Nizhny Novgorod refinery, several goals are achieved.”

The first such goal is to create a fuel shortage, necessitating the substitution of supplies from other refineries further away from the front itself. “In the case of warfare, stretching out logistics channels, causing a delay in shipments to the troops even by a week or two, can significantly change the picture at the front, where any hiccup in refueling heavy equipment changes the situation in areas with heavy fighting,” Dmitriev said.

The second goal is to strain Russia’s scarce air defense resources, as was done in the attacks on facilities in the Leningrad Region. It was there that, on January 31, Russian air defense forces first used the S-400 Triumf surface-to-air missile system in order to shoot down a Ukrainian drone. Every sophisticated air defense system redeployed to protect critical infrastructure deep in the rear on the home front means one sophisticated air defense system is available for protecting Russian positions in the actual combat zone. (As an added bonus, the installation of anti-drone electronic warfare systems is already causing communication problems in Russia’s Leningrad, Novgorod, and Pskov regions.)

Finally, a third, less obvious goal, is to create a shortage of rare rocket and aviation fuel, which, again according to Dmitriev, “does not have an infinite shelf life; its turnover takes about a month: from production to use.” As such, the most valuable targets on Russian soil would likely be those refineries that are part of the production chain of decylene — a specialized fuel used for Russia’s Kh-101/55/555 missiles, as well as the Kalibr, Kh-59 (both of which have been used to hit civilian ships in the ports of Odesa and the Danube) and the Kh-32. Such refineries could also be involved in production of the T-6 thermostable jet fuel, designed for long supersonic flights at high altitude using the “Onyx” engine (missile P-800). This type of fuel is currently produced by the refineries in Orsk and Angarsk, says Dmitriev.

Another possible goal is to reduce Russian budget revenues from the export of petroleum products. After all, the Tuapse refinery — now under repairs following a drone strike — was entirely export-oriented. Russian international fuel sales in January were significantly down, with diesel falling 23% and petrol 37% year-on-year.

However, this still does not represent a major hit to Russia’s budget. The export duty on all oil products in 2023 amounted to only 1.4% of the Russian government budget’s oil and gas revenues (126 billion rubles out of 8.8 trillion rubles). This means the Russian government can sometimes impose a complete ban on the export of oil products without losing revenues. In 2024, budget revenues will be even less dependent on exports, as customs duties have been reduced to zero (production taxes, on the other hand, have been increased, meaning that the money for the budget will come from the wells themselves, not from customs). Strictly speaking, it’s more profitable for the Russian budget to export crude oil than petroleum products made from it, because this way there is no need to spend money to compensate refineries for rising global prices (the so-called fuel dampener).

Estimates vary. According to Bloomberg, over the first seven months of the war the Russian invasion force burned through 180,000 tons of fuel per month (based on Russian Defense Ministry procurements of gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel for the six Russian regions bordering Ukraine, along with Ukraine’s Russian-occupied Donetsk and Luhansk regions). S&P analysts, however, put the figure of Russian fuel expenditures as of May 2022 at a total of 350,000 tons per month. Roughly speaking, Russia’s war in Ukraine is likely costing the country somewhere between 2 million and 4 million extra tons of fuel per year. (For comparison, in peacetime the entire Russian Army was estimated to consume 2 million tons of fuel and lubricants annually.)

According to The Insider's calculations, the 2-4 million tons that the Russian Army likely needed in 2022 represented only 1.5-3% of total fuel produced nationwide and 2-5% of domestic consumption. According to S&P estimates, the figure for diesel fuel is higher, with the Russian Army in Ukraine consuming 6% of the country’s total production in that category. Likely as a countermeasure, Russia has increased diesel production by 9% to 88 million tons since the beginning of the war.

It is unlikely that the military’s fuel consumption figures will decrease in the foreseeable future, as Russian troops are conducting at least two major offensive operations: on the Avdiivka axis near Donetsk and the assault on Kupiansk (with the plan to reach the left bank of the Oskol River). Accordingly, fuel consumption should be higher than when Russia was on the defensive — for example, in the fall of 2022, when Russian troops were retreating from Kharkiv and preparing to leave Kherson.

Another factor to be considered is winter, when fighting requires 50% more supply and logistical operations compared to summer campaigns. In winter, special diesel fuel designed not to freeze in subzero temperatures is a near necessity, and Russia traditionally produces less of it than it needs.

There is no doubt that the invading army is Russia’s main consumer of diesel fuel, and its needs create additional demand for diesel, especially in the south of Russia. While this factor alone did not cause the domestic Russian fuel crisis of summer 2023,it did affect the market.

The share of gasoline in the Russian Army's consumption structure may have increased, as civilian vehicles (like the Niva SUV or the UAZ-452 “Bukhanka” light truck) are often used due to the shortage of regular vehicles (the result of losses, the increased dispersal of positions on the ground, and the transportation needs of drone and electronic warfare systems operators). However, it is not possible to make an exact calculation of these figures, assuch vehicles are not registered with military units, and the military refuels them at its own expense.

Refineries in southern Russia, those closest to the combat zone, are of primary importance. However, as one oil and gas market expert explained to The Insider, mere geography is not the only factor at play. Not all refineries specialize in diesel and kerosene production, and some are primarily export-oriented — shutting down these refineries comes as no shock to the domestic market, nor to the military.

Taking into account all these factors, Ryazan and Samara may be the next targets, says The Insider's source: “Firstly, they are potentially achievable. And secondly, they play an important role in supplies for the army.”

Ryazan and Samara may be the next targets, according to an oil industry expert

The Ryazan Oil Refining Company, owned by state oil giant Rosneft, is the third-largest refinery in the country and the largest in Russia’s Central Federal District. Located a little more than 200 kilometers southwest of Moscow itself and roughly 600 kilometers from the Ukrainian border, the facility is capable of covering the Russian Army’s annual needs for gasoline (3.6 million tons), diesel fuel (4.5 million tons) and jet fuel (1.2 million tons) all by itself.

Three more Rosneft facilities offer similarly enticing targets for Ukrainian strikes. Near Samara, over 1000 kilometers east of Ukraine in Southern Russia, sit the Kuibyshev (7 million tons), Novokuibyshevsk (8.3 million tons) and Syzran (8.5 million tons) refineries.

Rosneft is likely the largest energy supplier to the Russian armed forces. The company’s sustainability report of 2018 showed that it had become the key supplier of supply lubricants to the Defense Ministry, the Investigative Committee, the Emergencies Ministry, the Interior Ministry, and Russian National Guard. (These contracts did not apply to jet fuel, which was supplied by a separate five suppliers.)

And yet, even if the refineries in southern Russia are successfully shut down by Ukrainian strikes, the country will find fuel for the army, experts interviewed by The Insider agree. As one of them explained, “the army will have no fuel only if they blow up all the refineries in Russia.” Otherwise, the experts said, “even if it has to come from Siberia, Russia will [find a way] to bring it.”

These same experts point to Russia’s railroads as being a key asset, as the in-country network would allow for the military toto restructure supplies relatively quickly in the event of major refinery outages closer to the front line. Freight trains are already used to transport oil over long distances, and the average distance of transportation of 1 tonne of oil cargo shipped by rail in Russia is more than 2000 kilometers. Shipping larger quantities over longer distances might prove to be a logistical challenge, but it is nevertheless a challenge that could likely be met. According to Radio Liberty, in November 2022 alone, the company Gazprom Neftekhim Salavat, which is based more than 1,500 kilometers east of Ukraine, in Russia’s Bashkortostan region, supplied more than 40,000 tons of diesel to Russia's border regions. Some of this may already be going to the needs of the army, as the plant has permits to produce diesel for the needs of the military.

Redirecting supplies within the region is an even easier task. Refineries are already shut down for one month every year in order to conduct scheduled repairs, and their output is redistributed to neighboring refineries. Still, this process is not always painless, especially when pressure is being put on the system by Ukrainian military action, as the 2023 diesel shortage demonstrated.

Russia does have a network of oil depots dispersed throughout the country. They hold stocks of fuel sufficient for several days or even weeks. These facilities, of course, help safeguard the system against unexpected shocks, but they also serve as a convenient target themselves. According to the writings of retired Major General Konstantin Shein and retired Colonel Alexander Smurov:

“In the Russian Federation, unlike in many countries of the world, there are practically no strategic reserves of oil, gas, petroleum products located in specially created, reliably protected underground storage facilities. About 11 million tons of petroleum products are stored in above-ground reservoirs located at the Federal Agency for State Reserves. The service life of most of these reservoirs exceeds 40-60 years, their operation in peacetime is very risky, and in times of war they would be easily destroyed. Today, Rosreserv [Russia’s Federal Agency for State Reserves] has only one underground (rock salt) facility for the storage of oil products, with a volume of about 0.5 million cubic meters — in Baikalia [east of Lake Baikal].”

Of course, there are no large oil depots in or near the combat zone, as they would immediately become a target for Ukrainian missiles. Therefore, in the event of a major supply shock, the mobility of the Russian military would depend on how quickly emergencies from such storage facilities could be organized.

If railroads fail, a pipeline could do the job. A portionof the Defense Ministry's reserves is already stored in Transneft's trunk pipelines. Trunk and field pipelines can deliver up to 60-80% of all petroleum products needed by the army, experts from the State Research Institute of Chemmotology believe. Theoretically, a special battalion could even lay a new oil product pipeline, but not instantly — the average installation rate is no more than 60 kilometers per day. (During the nine-year Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, over 6.8 million tonnes of fuel were delivered to the warzone from the USSR, with special units laying down two pipelines running 1,200 kilometers and meeting 80% of the need.)

Interestingly, Western sanctions complicate the task of repairs precisely because, in the years before 2022, so many of Russia’s Soviet-era refineries had been modernized in order to operate using foreign equipment. In the event of an accident (or a Ukrainian drone strike), the manufacturer will not sell a replacement. However, there are other ways to fix damaged equipment.

Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak claimed in December athat Russia has reduced the import dependence of its oil and gas engineering from 55% in 2015 to 35% today. .And refinery modernization continues even now, despite the sanctions. For example, enterprises of the Siberian Federal District have upped the output of petroleum products thanks to a “large-scale modernization of production.” The Bank of Russia writes: “In late September 2023, a new primary oil refining complex was commissioned at a Siberian refinery to produce gasoline, diesel fuel, and jet fuel.”

Some of the equipment is beginning to be manufactured domestically. “In Q3, machine-building enterprises continued to increase the output of innovative and import-substituting products, including equipment for oil and gas production and oilfield services,” the Central Bank's review said.

“Suppliers have already learned to procure many items that fell under restrictions through Turkey and China. It is safe to assume that they will also turn to Asia to find the equipment and components needed for repairs,” says a Russian oil and gas expert who wished to remain anonymous. However the enterprises may still face problems with software due to potential compatibility issues.

That said, large-scale repairs may not even be necessary. Disabling a refinery is not easy, and the temporary loss of the Rosneft facility in the southern city of Tuapse, which sustained the most damage from any Ukrainian drone attack so far, has not made a notable impact on the battlefield in Ukraine. Russian refineries have been built and modernized in line with standards developed back in the Cold War era, meaning that they are designed to be able to withstand the impact of a 1000-kilogram bomb and to suppress fires in the event that an explosion does occur.

So far, the drone attacks on both sides look more like an intimidation tactic than a genuine campaign aimed at wiping out the adversary’s energy infrastructure. Russia’s aerial campaign against Ukrainian infrastructure last year failed to paralyze the smaller country’s economy; it is no wonder that Ukrainian strikes have not had an appreciable visible effect on Russian energy supply.

Still, the Ukrainian side likely remains most vulnerable to a prolonged campaign of enemy strikes. As the Ukrainian military expert Dmitriev points out: “By destroying Ukraine’s storage infrastructure, Russia is achieving short-term, ‘here-and-now’ results. Moreover, the economics of such strikes does not always add up because the destroyed target should cost more than the attack itself. Ukraine has learned the lessons of massive strikes on oil depots and does not keep large volumes of fuel in one place, diversifying its sources of supply.”

So far, the damage from the drones has been negligible. In January 2024, Russian refineries reduced crude throughput by just 4% year-on-year, Kommersant reports. Due to the shutdown of its Tuapse facility, Rosneft saw a 10% decrease; Lukoil, which had an accident at the Nizhny Novgorod refinery, lost 8%. But in order to pick up the slack, others have ramped up production. The overall decline is the result of both downtime at major refineries and Russia's pledge to reduce exports of oil and oil products by 500,000 barrels per day in the first quarter of 2024.

“The incident at the Tuapse refinery did not cause any fuel shortages, because its supplies were more export-oriented,” Energy Minister Nikolai Shulginov stated.

Furthermore, Russia has ample emergency fuel reserves – almost 2 million tons of gasoline and 4 million tons of diesel fuel – and it has upped them by 16% and 7% respectively since January 2023, the Energy Ministry reports.

The Russian government regulates domestic retail prices for fuel, asking large companies to keep their price growth below the inflation rate. After the accident at Lukoil's Nizhny Novgorod refinery, Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak met with the management of other oil giants, asking them not to raise prices and to increase their domestic supplies until Lukoil has repaired its unit.

“Wholesale prices were already showing an increase. It is unrelated to Lukoil and started long before the recent incidents,” a fuel market expert states. “But poor expectations can trigger an additional growth of wholesale prices.” As a result, gas stations may see a drop in their profits.

We should not expect shortages in Russia's wholesale and retail gas markets yet, experts say

According to Rosstat, in January 2024 retail gasoline prices rose by 0.5% and diesel prices crept up by 0.1%.