Photo: Reuters / Dado Ruvic / Illustration / File Photo

In early December, the Trump administration released a new National Security Strategy that announced a sweeping overhaul of U.S. foreign policy. Built around the principle of “America First,” the document sharply narrows the range of issues Washington considers to fall within its national interest. But the text is riddled with contradictions — rejecting globalism while endorsing “resistance” to the policies of European governments, criticizing China while striking a softer tone toward Russia, and railing against the discrimination of Christians in Nigeria while pledging to reduce American involvement in Africa. Although the strategy signals a further cooling of relations between the U.S. and its traditional democratic allies, the new reality may offer Europeans an opportunity to unite in order to defend themselves and Ukraine, writes David Gioe, a visiting professor at the Department of War Studies at King’s College London and a former CIA analyst and operations officer.

In 1842, the American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow described a little girl who “when she was good, she was very good indeed, but when she was bad, she was horrid.” Much the same can be said of the Trump Administration’s National Security Strategy that was released on Dec. 4. While this NSS reads like the Trump Administration’s letter to Santa about how they wish the world to be, all administrations run headlong into an uncooperative reality. Bill Clinton faced an unwelcome Balkan War and famine in East Africa, George W. Bush suffered 9/11 before his resulting wars spiraled out of control, and Barack Obama contended with the Arab Spring and Russia’s invasion of Crimea.

National security strategies are inherently long-term tools of statecraft. Their deliberative horizon clashes — particularly in the case of the predictably impulsive Trump — with what conservative speechwriter Michael Gerson called “the eternal now.” While the chaotic Trump administration could benefit from a broad strategic framework to bring coherence and discipline to its overall foreign policy, recent history suggests that the NSS may be less a north star and more a shooting star in Trump’s ever-shifting constellation.

Still, this NSS is worth evaluating and understanding. After all, it lays out the second Trump administration’s view of the world, America’s place in it, the value of (some) allies, and the perspectives that will guide America for at least the next three years. Those who hoped for traces of George W. Bush’s decency toward Africa or Ronald Reagan’s commitment to opposing Moscow’s domination have instead seen confirmation that Republican foreign policy really has been fundamentally altered.

Indeed, there is more change than continuity for Trump NSS 2.0. Previous national security strategies from both political parties rested on the premise that the United States could not secure its interests by acting alone. They emphasized the importance of economic integration, alliances like NATO, and the defense of a rules-based international order. Threats such as Iran, terrorism, Russia, China, and North Korea were routinely identified in predictable hierarchies and then re-shuffled for a follow-on strategy.

In contrast, the second Trump administration has offered something quite different. Its NSS blurs the line between foreign and domestic policy, veering from U.S. history (“We want an America that cherishes its past glories and its heroes”) to public health (“raising healthy children”) to domestic policy (“historic tax cuts”). Culture-war preambles satisfied, it then turns outward.

The Trump Administration’s National Security Strategy blurs the line between foreign and domestic policy.

The administration promises a strategic correction that is to be achieved by elevating the Western Hemisphere, downgrading or ignoring traditional threat perceptions, and redefining alliances as transactional. It abandons the great power competition theme of Trump’s first term, makes no mention of North Korea or Cuba, and places American enrichment at the center of it all.

The NSS is also distinctive for its consistent focus on peace, which is actually rather unusual in national security documents. Were this insistence on peace written by a Democratic administration, it might be derided as naïve and Pollyannaish. Still, peace is indeed a worthy goal. Curiously though, one of the first actions taken by the “President of Peace” was to shutter the U.S. Institute of Peace.

This NSS is also the most personalistic ever written. It is unclear whether it is designed to guide U.S. foreign policy or to flatter the President. The de rigueur complaints about President Biden’s “weakness,” the complaints about out of touch “elites,” and the irreplaceable role of “presidential diplomacy” suggest the latter.

It is unclear whether the NSS is designed to guide U.S. foreign policy or to flatter the President.

More importantly, the strategy offers more contradictions than a freshman seminar on international relations: America should do less around the world but simultaneously stop regional conflicts before they spiral out of control. Part of America’s character is built on “decency,” yet peripheral countries and issues can be ignored. America should respect the political structures of other countries if they are monarchies or authoritarian states, except it should intervene in European democracies.

The introduction claims Operation Midnight Hammer “obliterated Iran’s nuclear enrichment capacity,” while the document later concedes more accurately that it “significantly degraded” it. These inconsistencies likely reflect the Trump administration’s haphazard national security decision making process, especially with the Secretary of State also serving as National Security Advisor.

The NSS claims the administration is already well on its way to bringing about a peaceful world. It is triumphalist about its accomplishments and takes a victory lap in claiming to have settled “eight raging conflicts.” While some of this is overstatement, the Trump administration does deserve credit for resolving certain disputes. Whether these agreements address underlying causes of violence remains an open question, but if they prove durable, the administration will surely deserve to claim credit.

Further, the NSS is correct in its diagnosis that American foreign policy has been unfocused and easily distracted since the end of the Cold War. It is also correct to oppose “fruitless nation building wars,” where the United States hemorrhaged blood and treasure without advancing U.S. national security at all.

After the Cold War, American policymakers convinced themselves that history had ended and that America was the indispensable nation, destined to drag globalization’s discontents into the 21st century — by force, if necessary, as in the Balkans or the Middle East. Here, however, the NSS overshoots. It claims “the affairs of other countries are our concern only if their activities directly threaten our interests.” Yet while America cannot be the global police force, there is a clear difference between recklessly invading countries and being uninterested in their development up until the point that certain problems become too pronounced to ignore.

The NSS makes the right noises about the value of partners and alliances, but here it undermines its efforts by treating alliances as conditional, as if they are worthwhile only if allies pay their way and align with U.S. commercial priorities. Further, the NSS channels a deeper, legitimate, and long-standing American frustration with shouldering a disproportionate share of the post–WWII security architecture.

The Trump, Obama, and Biden administrations were all fundamentally correct that wealthy countries should assume more responsibility for their own defense, even if the new document’s portrait of America playing a role “like Atlas” is Trumpian exaggeration. Yet the NSS fails to grasp the power of persuasion and trust when it comes to building alliances that produce long-term security benefits.

Its claim that the administration “rebuilt our alliances” will ring hollow for Canada, which Trump threatened to “make the 51st state,” and Denmark, whose autonomous territory Greenland Trump expressed the desire to annex. Durable alliances rest on shared values, shared interests, and, above all, trust.

The claim that the administration “rebuilt our alliances” will ring hollow for Canada, which Trump threatened to “make the 51st state.”

The NSS is also right to want to protect American ingenuity and intellectual property from espionage. In 2012, former National Security Agency Director Keith Alexander plausibly characterized cyber theft as “the greatest transfer of wealth in human history.” In the years since, however, America has still struggled with an effective response. The NSS is clear on the threat, but in practice, the Trump administration has diverted FBI counterintelligence agents to immigration enforcement and fired many more.

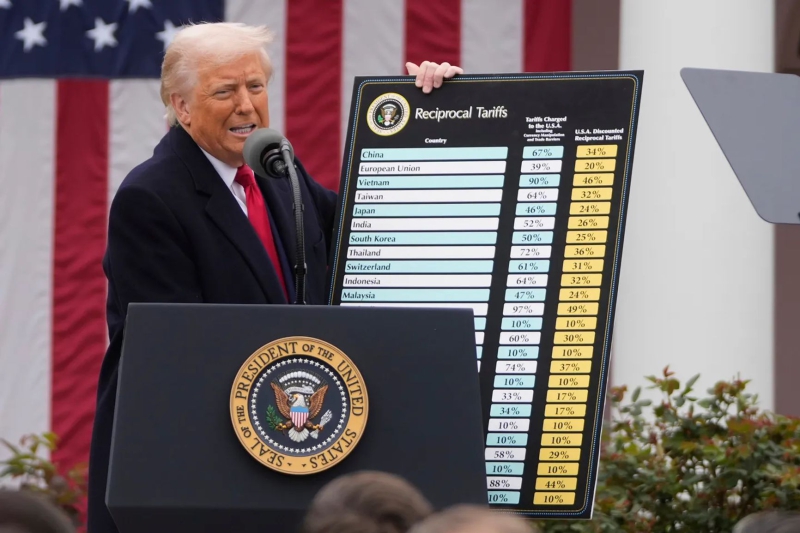

Likewise, the NSS is correct to desire a dynamic economy, secure supply chains, and a revitalization of the defense industrial base. Those are important goals, but tariff wars with Canada — America’s second largest trading partner — seem counterproductive if the aim is to secure reliable industrial sourcing.

The NSS is also right to insist that border sovereignty is fundamental to statehood. Similarly, protecting America from “hostile foreign influence, destructive propaganda, and influence operations” is essential. Yet the Trump administration took steps in the opposite direction by dismantling the State Department’s Global Engagement Center, downsized the Director of National Intelligence’s Foreign Malign Influence Center, and disbanded the FBI’s Foreign Influence Task Force, all of which worked to combat precisely those threats enumerated by the NSS.

Where the NSS is most clear-eyed is in its assessment of China. The document devotes the greatest intellectual effort to addressing Beijing’s predatory trade practices and abusive economic behavior. The drafters are not incorrect to observe that successive U.S. administrations operated under the mistaken belief that commercial engagement would transform China into a responsible stakeholder.

In retrospect, this fanciful accommodation enabled China’s rise even as Beijing continued to bully its neighbors, repress its citizens, and steal foreign intellectual property at scale. The West’s economic openings made China indispensable to Western consumers, while Beijing shamelessly exploited every opportunity to continue breaking the rules.

As usual, Africa is covered last, presumably because this placement in the document reflects its position on the periphery of U.S. interests. However, the quantity of lives saved in Africa over the past two decades thanks to the distribution of antiretroviral drugs represent a minor miracle. These efforts increased America’s soft power — something the NSS says it wants but that it clearly does not understand how to get. Similarly, although the NSS speaks twice about American “decency,” it is hard to square that ideal with a strategy organized around hard-nosed economic domination.

The distribution of antiretroviral drugs in Africa increased America’s soft power — something the NSS says it wants but that it clearly does not understand how to get.

Here too, however, there are seeming ideological inconsistencies. If ignoring developments peripheral to America’s narrowly defined national security interest were really the organizing principle of American power, it would seem strange that Trump ordered the Pentagon to prepare a plan to protect persecuted Christians in Nigeria — a non-trivial task in a country of 237 million that covers an area larger than every U.S. state except Alaska.

Still, in contrast to its solid assessment of China, the NSS is at its most horrid on Europe and Russia — this despite using the correct formula of “Russia’s war in Ukraine,” a phrase signaling a baseline understanding that Russia is the aggressor and Ukraine is the victim. However, the administration’s consistent subservient posture toward Russia — appeasing Putin while neglecting Kyiv militarily and rhetorically denigrating Zelensky — undermines the moral clarity of the words on paper. Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov declared the NSS to be “a positive step,” noting that the strategy’s “adjustments are largely consistent with our vision.” It is hard to think of a more perverse endorsement of an American document.

The NSS claims “many Europeans regard Russia as an existential threat,” but it fails to note why. Europeans have been victims of an increasingly reckless form of Russian sub-threshold warfare: intimidation, assassination, sabotage, malign political influence, disinformation operations, undersea cable cutting, frequent airspace violations, and more.

The NSS then raises demographic anxieties, arguing that “certain NATO members will become majority non-European,” begging unanswered questions about what it means to be European. The strategy suggests that America should cultivate internal resistance to Europe’s current trajectory, a step that would seem hypocritical given the administration’s claims to want no foreign interference within the United States.

By approvingly referring to “patriotic” political parties in Europe (code for the far right), the NSS actually mirrors Russian interference efforts in European politics, where Moscow similarly cultivates far-right movements as part of its strategy to break apart NATO and the EU. The NSS then escalates to the absurd when it envisions placing the United States as a diplomatic interlocutor between Russia and Europe as part of a purported effort to prevent European actors from aggravating the tensions.

This is precisely backwards. Some European capitals have finally awakened to the threat of a revanchist Russia, and U.S. strategy should place the American arsenal of democracy at Ukraine’s disposal, not place American diplomats between Moscow and Brussels.

On Ukraine, the NSS declares that negotiating an expeditious cessation of hostilities is a core U.S. interest, yet it seems confused about how to achieve this goal. For nearly a year now, the administration has shown obeisance to Moscow’s demands, hosting a distasteful red-carpet summit in Alaska and pressing Kyiv to accept a Russian-derived “peace plan” that was tantamount to surrender. Analysts overwhelmingly agree that the most promising path to peace is to convince Putin that peace is his only route forward, something that requires arming Ukraine sufficiently to defeat the occupying force and the bases that supply it.

Analysts overwhelmingly agree that the most promising path to peace is to convince Putin that peace is his only route forward.

While the NSS correctly notes that European militaries must do far more for their own defense, the administration’s culture-war grievances regarding European institutions, demographics, and alleged “civilizational erasure” advance neither American nor European security goals.

Most outrageously, the NSS claims that the real obstacle to peace in Ukraine is European governments’ subversion of democratic processes. True, despite the reality of a “large European majority wanting peace” the war rages on. Still, since the NSS appeals to U.S. history to underscore some of its points, its drafters could perhaps have recalled that, during the American Revolution, a large colonial majority wanted peace with Great Britain, while a sufficient number of patriots nevertheless understood that a period of war and deprivation was inevitable before the desired peace could arrive.

The Atlantic Ocean seems wider after the publication of this NSS. European commentators responded with understandable disappointment. What was less understandable was their seeming shock. Anyone surprised by this document quite simply has not been paying attention. Those calling the NSS a “wake up call” for Europe must have missed the previous hundreds of wake-up calls, including the one delivered by Vice President J.D. Vance last February in Munich and the one delivered when Volodymyr Zelensky visited the White House later that month.

If Europeans now, finally, can clearly understand where they stand in this administration’s estimation, there is at least an opportunity for them to coalesce in a meaningful way. Taken together, NATO’s non-U.S. members still enjoy a hard power advantage over Russia in almost every category except nuclear weapons. Europeans should indeed be able to do more for themselves — and for Ukraine — than they have up until now. This is a moment of clarity not to be missed.