Photo: Getty Images

After American forces removed Nicolas Maduro from Venezuela earlier this year, the U.S. began pushing Russian companies out of the country, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov alleged recently. Despite the partnership agreement Moscow had signed with Caracas, Russia limited itself to verbal condemnations of U.S. actions. Before that, Iran received no tangible support from Russia after Israel and America conducted twelve days of strikes against Tehran’s nuclear program, and Trump’s threats to retaliate against the ayatollahs over their violent crackdown on nationwide protests was met with similar inaction from the Kremlin. Vladimir Putin is silently making concessions to Donald Trump, seemingly in the hope that the two leaders may yet agree to divide the world’s “spheres of influence” between them, writes international security expert Eliot Wilson. However, in Wilson’s view, a Cold War-style realignment of the geopolitical map is unthinkable today — hindered by Trump’s unpredictable volatility, Russia’s inevitable clashes of interests with the United States, and China’s growing strength.

Sir Winston Churchill famously described Russia as “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” He was speaking only a few weeks after the Soviet Union, following its astonishing agreement of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact with Nazi Germany in 1939, followed Adolf Hitler’s lead and invaded Poland. The episode served to remind western Europe how little it really understood the Kremlin and how impenetrable the thinking of a leader like Stalin seemed to be.

Trying to understand the dynamics of the relationship between Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin can sometimes make you think we have scarcely learned anything in the intervening nine decades. Writing for GQ in 2017, journalist Peter Conradi characterised the situation as a “bromance,” which seemed to capture its unlikely nature if nothing else.

Like almost all of Trump’s relationships, it has been volatile, but there is a persistent, lingering sense that he finds something attractive, perhaps admirable, in the former KGB officer who has now controlled Russia for more than a quarter of a century.

There is a persistent, lingering sense that Trump finds something attractive, perhaps admirable in the former KGB officer who has now controlled Russia for more than a quarter of a century.

The interaction between the two elderly leaders — Trump turns 80 this year, while Putin will be 74 in October — has become hugely important for negotiations to end the war in Ukraine. Too often, such efforts have become a bilateral issue, with President Volodymyr Zelensky pushed to the sidelines. Before his re-election in November 2024, Trump boasted repeatedly that he could bring the conflict to an end within 24 hours, and on Feb. 12, 2025, he held what he called a “highly productive” telephone call with Putin in which the two leaders agreed to “have our respective teams start negotiations immediately.” Nearly a year later, there is no indication that any kind of ceasefire or peace agreement is imminent.

The rest of the world has not stood still while the elaborate dance of diplomacy plays out. Nothing happens in isolation. The talks on Ukraine and relations between the United States and Russia have to be placed in their proper context, and the events of the last few months have provided more than enough context.

Forgotten by Putin

The first important element is America’s arrest, extraction, and arraignment of Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro from a supposed safe house in Caracas. Operation Absolute Resolve was a meticulously planned, perfectly executed coup de main that took barely two hours and left the international community dumbfounded. Many weeks later, there are questions as to the next steps given that Maduro’s deputy, Delcy Rodríguez, has been sworn in as acting president, more or less keeping the old regime in place.

Washington’s poor track record in régime change and nation-building, combined with Trump’s all but non-existent attention span, suggest that the greatest challenges may be yet to come. But what has been the reaction from Moscow?

Last May, Putin and Maduro signed a 10-year strategic partnership which provided for technical cooperation in the oil industry under the OPEC+ framework, and for military cooperation that included Russia’s delivery of Buk-M2E air defence missile systems. After all, Maduro was not blind to the potential threat of U.S. military action against him.

An alliance with Venezuela also gave Russia strategic reach with a toehold in the Caribbean. Last October, in a move deeply reminiscent of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, the First Deputy Chairman of the State Duma Committee on Defence — hawkish nationalist Alexei Zhuravlyov — returned to a theme he had previously invoked, warning that Russia could deploy nuclear-capable missiles to “Venezuela or Cuba,” which are conveniently located a short flight away from Russia’s “main geopolitical adversary.”

That same month, Maduro appealed to Putin to send anti-aircraft and anti-missile defence systems in response to the American military build-up in the Caribbean. Putin, however, did little to assist his ally. After Maduro’s anxieties were vindicated by January’s events, the Russian Foreign Ministry condemned Operation Absolute Resolve as “an act of armed aggression” and reaffirmed its “solidarity with the Venezuelan people and… protecting the country’s national interests and sovereignty”. But there has been no action, and the defenestration of Nicolás Maduro is now a fait accompli.

When Maduro appealed to Moscow to send weapons to Venezuela in response to the American military build-up in the Caribbean, Putin did little to assist his ally.

How should this be interpreted? On the one hand, other clients of the Kremlin could be forgiven for feeling a heightened degree of vulnerability as they check the small print of treaties and agreements. Cuba and Nicaragua, for example, have close links with Russia, but their location within the sphere of the Monroe Doctrine and its new and aggressive “Trump Corollary” makes them potential targets for U.S. intervention. Is Putin’s influence in Havana and Managua diminished?

Similar doubts might be felt in Tehran. Trump has threatened dire retribution against the régime if it continues its savage repression of protesters, brutal efforts that have already caused thousands, perhaps tens of thousands, of deaths. The American president said that Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, should be “very worried,” and on his Truth Social platform, Trump announced that “a massive Armada is heading to Iran… ready, willing, and able to rapidly fulfill its mission, with speed and violence, if necessary.” He was referring to the U.S. Navy’s Carrier Strike Group 3, which is centred on the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln.

Iran and the United States are now engaged in talks in Oman over the status of the Iranian nuclear programme, though those discussions have been fractious and remain fragile. Iran’s official rhetoric has remained defiant and hard-edged: Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi said his country’s armed forces had “their fingers on the trigger” and were prepared to “immediately and powerfully respond” to any American aggression.

Any constructive outcome from the negotiation process must be in the balance given that the U.S. delegation is being led by Trump’s special envoy Steve Witkoff, who has been dubbed “Dim Philby” as a result of a tendency to believe everything rival interlocutors tell him. It is also not clear exactly what each side wishes to achieve. The talks are ongoing, however, and one reason may be the fact that the Iranian government knows Russia will not — cannot — ride to its rescue.

A quiet shake-up

We need to consider whether this is part of a wider foreign policy play by Vladimir Putin. The recent publication of America’s National Security Strategy (NSS) was revealing in many ways. It noted that “managing European relations with Russia will require significant U.S. diplomatic engagement,” but it also described the necessity to “reestablish strategic stability with Russia” as a core national interest. Still, the word “Russia” appears only 10 times in the document — compared to 24 for “hemisphere,” 21 for “China,” 13 for “immigration” or “migration,” and 27 for “Trump.”

America’s new National Security Strategy described the necessity to “reestablish strategic stability with Russia” as a core national interest.

The NSS states that America will “support our allies in preserving the freedom and security of Europe,” but it also sets out a «predisposition towards non-interventionism” and a “focused definition of the national interest” as basic principles. Combined with references to burden-sharing, it is fair to assume that these represent a likely reduction of military commitment in Europe — notably, when the document says that “many Europeans regard Russia as an existential threat,” it implies strongly that the United States does not.

It may be that Vladimir Putin sees an opportunity here. He knows that Trump is fundamentally uninterested in the conflict in Ukraine. What keeps the American president engaged is a manifold confluence of self-interests: the lure of a “deal” that would add another conflict to his dubious list of “ended” wars, along with the potential material advantage in exploiting Ukraine’s mineral resources in the light of last April’s agreement on a reconstruction investment fund and rights to “any Natural Resource Relevant Assets.”

Given that Trump has no attachment to the more principled points at stake in Ukraine — punishing war criminals and violators of international law while upholding the norms of self-determination and the sovereignty of all states — Putin will understand that many options are open to him. One of his duties during his 16-year career with the KGB, which is the enduring lens through which he sees the world, was identifying anyone who could be converted into a political sympathizer — or even an ally.

Trump has no attachment to the more principled points at stake in Ukraine — punishing war criminals and violators of international law while upholding the norms of self-determination and the sovereignty of all states.

Putin knows that Trump has a deep antipathy towards Ukrainian president Zelensky, whom he has publicly blamed for starting the conflict. Conversely, Trump has often demonstrated warmth towards Putin, extending him the benefit of the doubt even in the face of evidence from America’s own intelligence community. Throughout the tortuous and so-far-fruitless “peace” talks over Ukraine, Russia has consistently sought to present itself to Trump as the reasonable party — the kind of country he can do business with in order to successfully reach a negotiated end to the conflict. Trump has sometimes accepted this false Kremlin narrative with alarming ease and enthusiasm.

To some extent, there is a meeting of minds between Putin and Trump. Both admire explicit, sometimes grotesque displays of strength, and both insist that their countries were stronger and more powerful in the past. Both are disdainful of international norms and multilateral organisation. And it does not require much imagination to see Putin’s covetous interest in Russia’s blizhneye zarubezhye — or “near abroad” — as a Slavic-accented interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine.

In short, Putin might see a future in which he and Trump agree (to adapt Kipling’s verse) that “East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.” Further American disengagement from Europe and from supporting Ukraine would be matched by Russia distancing itself from its former allies in Latin and South America, and perhaps in the Middle East too, as each “superpower” is given the freedom to dominate its own hemisphere.

It is an appealingly neat narrative. Under a more ordinary President of the United States, it might even be a plausible approach for Putin to pursue. The nature of Donald Trump, however, suggests it is not sustainable in the long term.

Reality vs. rhetoric

The first obstacle is Trump’s sheer unpredictability. Any kind of tacit non-aggression pact would rely in part on a degree of self-denial, an understanding that there are areas and issues each party will set aside. Trump’s impulsive and often reckless responses, fired instantly into the geopolitical ecosystem on social media, would make that impossible. It is easy to forget how deadened our senses have become in the nearly nine years since the American president characterized Kim Jong Un as “little rocket man.” The utterance of remarks that once would have sparked a serious diplomatic scandal have now become almost everyday occurrences.

Any kind of tacit non-aggression pact would rely in part on a degree of self-denial — which would be impossible with Trump.

Putin has contributed to this development too. Although he is infinitely more calculating than Trump, the Russian leader is more than capable of deploying rhetoric which raises the stakes. When he began the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, he warned “those who may be tempted to interfere from the outside” that “Russia will respond immediately…and the consequences will be such as you have never seen in your entire history.”

Even setting aside the individual personalities of the two leaders, there are areas where the interests of the United States and Russia are bound to collide. Although America’s National Security Strategy does not mention the Arctic, its National Defense Strategy does: under the heading of “Homeland and Hemisphere,” it notes that “we have seen adversaries’ influence grow from Greenland in the Arctic to the Gulf of America.” It then states that the Department of Defense “will therefore provide the President with credible options to guarantee U.S. military and commercial access to key terrain from the Arctic to South America, especially Greenland.”

Meanwhile, Putin has been expanding Russia’s presence in the Arctic, from which it derives much of its oil and gas. He has also been positioning Russia as a major interlocutor in political dialogue around the topic, hosting last year’s International Arctic Forum.

Trump’s impulsiveness also frequently contradicts his professed “America First” approach to foreign policy, and it does so in ways which will inevitably engage Russian strategic interests. The Kremlin was, for example, heavily invested in backing Bashar al-Assad’s régime in Syria, not least because the development of the naval base at Tartus gave Russia its only direct access to the Mediterranean Sea. The future of that facility is now in doubt, while the White House has leaned towards supporting the new interim Syrian government of Ahmed al-Sharaa. It is impossible to predict the final status of that triangular relationship.

The China factor

There is one other factor which cannot be ignored anywhere across the globe: the People’s Republic of China. If Russia is enigmatic, China is proverbially “inscrutable.” Western observers find it extremely challenging to fully comprehend a culture that has developed almost entirely separately from our own and which draws on traditions of state machinery and bureaucracy that are more than 2,000 years old.

This has to be balanced against the reality of a state which has transformed itself within living memory. The People’s Republic and the sole authority of the Chinese Communist Party will only mark their 77th anniversary later this year. In the first 25 years of Communist control, the population of China almost doubled, from 550 million to 900 million, and after 1978, Deng Xiaoping’s “economic miracle” saw the country become the world’s second-largest economy. Think of it like this: when Donald Trump’s beloved ghost-written book The Art of the Deal was first published in 1987, China was the eighth-largest economy, representing less than two per cent of global GDP.

How does China fit into the U.S-Russia matrix? The simple answer is “awkwardly,” which is exactly the way Beijing wants it to be.

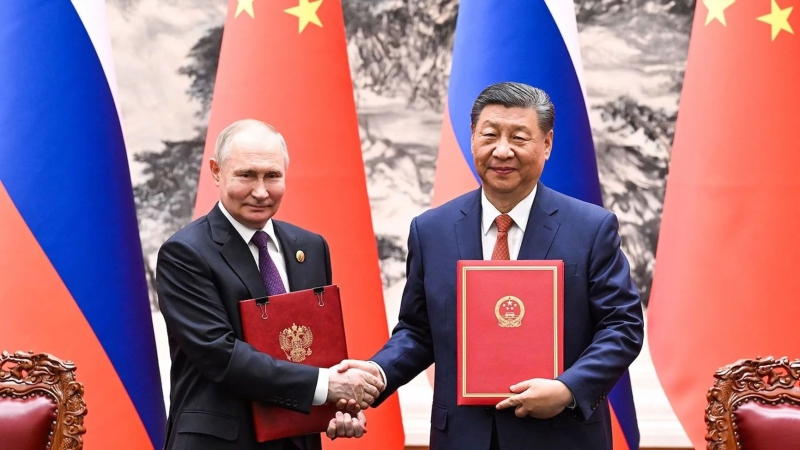

China has aligned itself closely with Russia. In May 2024, Putin travelled to Beijing, where he and Xi Jinping signed a Joint Statement on Deepening the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership of Coordination for the New Era. This has put Moscow and Beijing on the same page in terms of economic, technological, and political coordination and provided Russia with a valuable source of trade and resources.

At the same time, the United States clearly regards China as its major geopolitical competitor. The National Security Strategy states that Trump’s foreign policy will seek to “rebalance America’s economic relationship with China, prioritizing reciprocity and fairness to restore American economic independence. Trade with China should be balanced and focused on non-sensitive factors.” Part of this strategy is aimed at discouraging any attempt by China to take control of Taiwan, “ideally by preserving military overmatch.”

Still, the situation is not as simple as it seems, and it should not be said outright that China is “on Russia’s side” or “against America.” Beijing regards itself as a third actor that is in no way subordinate to the other two countries. America’s tone towards China under the second Trump presidency is one of warning, but not of hostility. After all, it emphasises potentially prosperous economic relations.

In terms of its Russian ally, China undoubtedly perceives itself now as the senior partner. It has supplied military materiel to the Russian war machine but, unlike North Korea, has not contributed troops to the war in Ukraine. China is also engaged in increasing its stockpile of nuclear warheads at a rapid pace, but it is nevertheless believed to have acted as a restraint on Putin’s nuclear brinksmanship with the West.

In terms of its Russian ally, China undoubtedly perceives itself now as the senior partner.

China is pursuing a long-term, transactional policy. It currently suits the PRC to stand with Russia and to emerge as the senior member in their “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.” But it will not let that alliance affect its relations with the United States, which is explicitly open to some kind of co-existence. While traditional rivals America and Russia face off in a new form of an old confrontation, China will pursue its own interests.

In their own ways, both the United States and Russia want and expect to be global powers with a global reach. Although America clearly has superior resources to help it pursue that ambition, Russia is not going to retreat behind its ramparts and leave the field to Trump and his successors. Under the current conditions, tensions between Washington and Moscow could be as volatile as the American president’s rhetoric.