Russian military intelligence (GRU) enlisted an Estonian pro-Russian propagandist to orchestrate a series of vandalism acts designed to intimidate and silence critics of Russia within Estonia. The targets of these attacks included the country’s interior minister.

On the morning of December 8, 2023, Estonian Interior Minister Lauri Läänemets awoke to an unpleasant surprise. His wife informed him that overnight the family car, a gray Volkswagen Passat parked near his private home in Tallinn, had been vandalized, all of its windows shattered. “I immediately suspected this wasn’t random vandalism,” Läänemets said. “The windows had been broken systematically, yet nothing was stolen. But I couldn’t guess what exactly it was about at that moment.” In fact, Läänemets and his family were being surveilled by hirelings of a foreign intelligence service.

Only hours earlier, Allan Hantsom, a pro-Russian activist in Estonia, had been preparing to flee the country. His belongings were packed and the moving trucks were ready and waiting. Hantsom knew it was his last day at home; his apartment had already been listed for sale for some time. Then he heard something. It certainly wasn’t a knock. Was it the sound of a door being forced open?

Moments later, Hantsom found himself with his hands behind his back, his rights being read to him. Officers from the Estonian Internal Security Service (KAPO) stood beside him, while others began combing through his belongings.

Hantsom had been handed a list by Russian military intelligence, the GRU. This list contained the names of people in Estonia who were to be targeted. The purpose of these attacks was not just to intimidate the victims but to spread fear across the country: to stoke tensions, sow division, and send a message that Russia could operate with impunity even beyond its borders, starting with its nextdoor neighbors.

Estonia has a long history of combating Russia’s hybrid attacks. In 2007, the infamous Bronze Night riots unfolded, centered on the relocation of a Soviet World War II monument from a busy intersection in Tallinn to a nearby war cemetery. Pro-Russian hooligans, egged on by Kremlin disinformation, incited days of unrest culminating with a massive cyberattack against Estonia later linked to Russia.

Hantsom has been a central figure in these provocations. He was a notorious pro-Russian activist frequently seen at protest events alongside members of the Immortal Regiment, a Russia-originated civic initiative founded in 2012 to honor Soviet soldiers who fought in World War II. Over time, and especially following Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine and its takeover of Crimea, the Immortal Regiment became an instrument for Russian nationalism and a rallying point for Putin loyalists, particularly the Russian diaspora. In its publicly released 2016 annual review, KAPO noted that Immortal Regiment activities in Estonia “are directed by Allan Hantsom.»

Beyond his pro-Russian activism, Hantsom worked as a propagandist for Sputnik Estonia, a local branch of the Kremlin-funded media outlet operated by Russia’s state-owned Rossiya Segodnya. Widely regarded as a tool of Russian disinformation, Sputnik was shut down in 2022, with its operators prosecuted for sanctions evasion schemes designed to circumvent EU-imposed restrictions following Russia’s invasion of Eastern Ukraine in 2014.

Hantsom was also a GRU asset. It’s unknown when he was recruited, but his arrest would lead to the unmasking of more culprits, a network of agents and sub-agents, most of them unaware as to who their masters in Russian military intelligence were. One apparatus nested within another, like matryoshka dolls. The GRU was behind it all, however, in a stealth effort to intimidate the NATO member-state with which it shares a 200-mile border.

This exclusive, which The Insider conducted with Delfi, Estonia’s leading news outlet, is based on conversations with people close to the KAPO investigation into the GRU’s vandals-for-hire campaign.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the GRU has relied increasingly on remote-recruited and remote-controlled actors — native Europeans in most cases, many of them riff raff or petty criminals — to carry out the sort of kinetic operations trained Russian operatives used to do. The GRU is resorting to methods similar to what ISIS used when its caliphate in Syria and Iraq collapsed and it could no longer send its own lieutenants into Europe to conduct terror operations: it found them remotely. The GRU uses cutouts on Telegram to find willing accomplices, whom it compensates in cryptocurrency. The dependency on native Europeans to carry out Russian intelligence orders owes both to enhanced travel restrictions in Europe for Russians since the war in Ukraine started and also to the GRU’s long, sordid track record of mokroye delo, or “wet work,” in the West. Many of its most capable operatives, particularly those attached to black ops team Unit 29155, have been identified by The Insider and its investigative partners and subsequently indicted by European governments for poisonings, insurrections, cyberattacks, and the destruction of ammunition and weapons depots carried out over the past decade.

Acts of Russian state terrorism are now growing in tempo, scale and ambition, in tandem with continued Western support for Kyiv’s defensive war against Moscow. “This year there were 500 suspicious incidents in Europe,” Czech Foreign Minister Jan Lipavský said in Brussels on December 4. “Up to 100 of them can be attributed to Russian hybrid attacks, espionage, influence operations.” Culprits tied to these operations have been arrested in the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Poland, Czechia, and the Baltic Sea region. Their targets for arson or bombing attacks include industrial sites, defense plants, shopping malls, bus depots, and museums. Cyberattacks, or threats of them, are another area of concern. There’s been at least one assassination attempt, against Armin Papperger, the CEO of Germany's largest arms manufacturer, Rheinmetall (a major supplier of weapons to Ukraine), and one near-miss mid-air detonation of an incendiary device aboard a DHS cargo plane en route from Leipzig to Birmingham.

The GRU’s reliance on amateurs has yielded a mixed bag of results. But that doesn’t mean Western counterintelligence and law enforcement agencies aren’t alive to the escalating threat — and for the greater likelihood that people will get killed. “We are simply too polite,” Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen said recently at the margins of July’s NATO summit in Washington, D.C. “They are attacking us every day now.”

Just after Hantsom’s arrest, the first two cars were vandalized. The first was Läänemets’s Passat. The second was a white compact SUV belonging to the family of Andrey Shumakov, the editor-in-chief of Russian-language Delfi. His car had four passenger-side windows broken.

When Shumakov arrived home after receiving a call from his wife, the police were still nowhere to be seen. By then, Shumakov had already read about what had happened to Läänemets’s car. He called the police spokesperson and said, “It’s the same case, same perpetrators — the pattern is too similar to ignore.” By the time Shumakov returned from picking up his child at the bus station, the yard was swarming with police officers collecting footprints and other evidence.

“We weren’t scared,” Shumakov recalled. “We thought it was just some hooligans.” Later, when the Internal Security Service informed him that the attack had been orchestrated by Russian intelligence, he remained remarkably calm. “I don’t remember being frightened,” he said.

No further attacks occurred. According to Delfi’s sources, the Internal Security Service found a list of targets and warned everyone on it. The list reportedly included around a dozen names. According to those familiar with its contents, the list followed a specific logic: alongside prominent politicians, it featured journalists and individuals closely followed by Estonia’s Russian-speaking population. These were people who openly exposed the falsehoods of the Russian regime’s official narratives about the war in Ukraine and, even more damagingly, the miserable reality of life in Russia. They were undermining the Kremlin’s efforts to maintain discontent among the ethnic Russian population in Estonia, around 25% of the total, which was vulnerable to pro-Kremlin disinformation sources that portrayed life in Russia’s crumbling provincial cities as idyllic.

Following Hantsom’s arrest, the authorities swiftly rounded up other members of the surprisingly long chain involved in the attacks. The vandals were tied to organized crime and had no idea whose windows they were smashing or why. They were simply promised a few thousand euros to carry out the job.

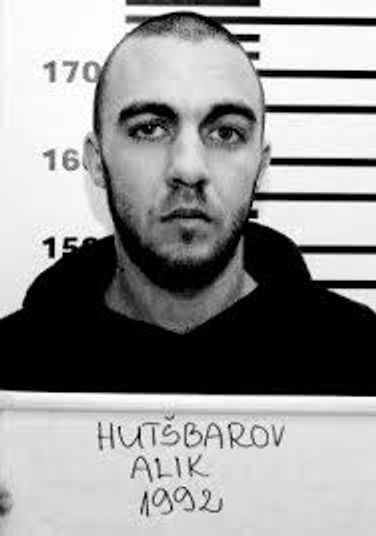

One of Hantsom’s collaborators in the GRU’s Estonia network was Alik Huchbarov. Born in the Pechory region of Russia, Huchbarov had received an Estonian passport in 2006 thanks to his ancestry. (Pechory was part of Estonia until 1944.) That document defined his future.

Using the passport, Huchbarov started smuggling contraband. It was easy: he’d simply walk across the border from Pechory to Piusa, the Estonian town on the other side, in the south of the country, encountering no additional checks or barriers — after all, the Estonian state doesn’t harass its own citizens. At first, Huchbarov smuggled cigarettes and other small items. Then the stakes grew higher. He began smuggling people, ferrying Vietnamese migrants to the border. This new line of work meant securing protection from Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB), which controls the country’s Border Guard.

Under their protection, Huchbarov was free to operate, unbothered by Russian authorities. However, such arrangements always come with strings attached. Eventually, the FSB instructed him to work for them. Huchbarov obliged, gathering intelligence on Estonian border police at the Piusa border checkpoint and passing it along.

Seven years ago, KAPO apprehended Huchbarov. He was prosecuted, convicted, and sentenced to three years in prison. Upon his release, he left for Russia and switched employers within the Russian special services. He began working for the GRU.

Huchbarov isn’t believed to hold a particularly high rank within the Russian military intelligence agency. Instead, he acts as a liaison between GRU officers and their agents. He was an ideal candidate for such a role: despite being convicted of crimes against the state, his Estonian passport was never revoked. Even after becoming a contact for Russian military intelligence, Huchbarov continued crossing the border freely, showing his Estonian passport and traveling wherever he pleased without restriction.

Initially, Huchbarov was tasked with recruiting others like himself. The goal was to create the impression that the attacks were being carried out by local residents, suggesting that Estonia’s own society was divided, rife with domestic discontent for which Russia was not to blame. The task wasn’t overly challenging. There are an estimated 10,000 people with dual citizenship living near the Estonian border in Russia.

According to KAPO, both the FSB and GRU have been increasingly successful in recruiting individuals who can go back and forth as they choose. The recruits are instructed to vandalize, spy, and carry out attacks, not just in Estonia but in other NATO countries — where they enjoy the same unrestricted access thanks to Estonia’s membership in the Schengen Zone, which allows for visa-free travel to 29 European states.

Another one of Hantsom’s contacts in Russia was Ilya Bocharov who, according to The Insider’s sources, is also connected to GRU and worked in tandem with Huchbarov on several recruiting “projects.” From his public profile, Bocharov seems to be a boxing trainer in St. Petersburg and a blogger with close to 100,000 followers on the platform Dzen.

Hantsom was promised money if he could orchestrate the vandalism of around ten cars belonging to specific targets. Deadlines were agreed upon with his GRU handlers, and everything was to be completed within a few months. To carry out the task, Hantsom called his old friend, Andrei Kolomainen, and offered him a share of the €10,000 the GRU had offered him to smash up vehicles. He explained whose cars needed to be targeted and why. Desperate for money, he took on the task of building a subnetwork of unwitting GRU agents that would carry out the attacks.

In his younger years, Kolomainen worked as an Estonian police officer. Around two decades ago, he made headlines for all the wrong reasons. One day in 2002, while on duty in Tallinn, he picked up a homeless man in his patrol car. He drove the man to a remote wooded area in Paljassaare, a small peninsula in Tallinn, and savagely beat him, leaving him helpless on a forest path. Kolomainen did this to other homeless people, and, eventually, his brutality caught up with him: he was fined three months’ salary for “abuse of power” and fired from the police force.

In 2013, Kolomainen reinvented himself as the leading force behind the political movement Rodina (Russian for “homeland”). He officially registered Rodina’s candidate list for local elections, advocating for the legalization of drugs, prostitution, polygamy, and easier access to firearms. Among the candidates on this list was Allan Hantsom, with whom Kolomainen struck up a close partnership. (Kolomainen largely works behind the scenes of his own organization; his day alternates between driving a taxi and working construction.)

Kolomainen reached out to one his subcontractors in the construction industry, Anatoli «Tolik» Russin, a burly, tattoo-covered career criminal who a decade ago was caught attempting to traffic over half a kilogram of Ecstacy tablets. He didn’t act alone — Russin was a key member of the long-established Estonian-Russian underworld led by Gennadi Okunev.

Okunev valued Russin’s loyalty, even supporting him financially during his time in prison. Upon his release, Russin resumed his role in Okunev’s crew, serving as an “elder,” or senior figure overseeing new recruits. Russin was entrusted with managing drug operations, collecting funds, and resolving disputes, often through violence, including beating people who owned Okunev money until they paid up. When Russin was arrested again in 2019, he avoided jail time, receiving only a suspended sentence.

Despite such a chequered career, Russin wasn’t exactly gung-ho about destroying cars. When Kolomainen approached him he decided to outsource the work to third parties, two old acquaintances with rap sheets involving drugs and assault, Maksim Nesterenko and Teimur Mussayev. Russin offered them a few thousand euros to break car windows. Despite the relatively low risk, Nesterenko and Mussayev, too, hesitated.

“This was already street-level culture,” Estonian state prosecutor Triinu Olev-Aas told The Insider. Responsibility was passed down the line for plausible deniability and any direct communication about the tasks was avoided. Instead of texting or messaging, the group met in person. It operated more like a spy ring than a gang.

At the same time, the recruits were lazy. They complained it was too cold out to break windows. Then they started outsourcing work themselves. Eventually, Mussayev and Nesterenko found Mihhail Malanskas, a 21-year-old drowning in debt. Although he had no significant criminal record, he had previously been caught with drugs and committed traffic violations.

It was Malanskas who, on the night following Hantsom’s arrest, smashed the windows of two cars. Months later, when KAPO apprehended him, Malanskas had no idea that he had been carrying out tasks for the GRU.

By now, all of the people in the network have been charged and sentenced, but the exact details about the case have not been revealed to the public. None of the participants in the chain ever saw the money they were promised, and no help has come from the Russia intelligence service responsible.

“This is a GRU hallmark,” said Olev-Aas. “Their collaborators are always left to fend for themselves.”

After the arrest, Allan Hantsom quickly broke, requesting a deal for a lighter prison sentence. He received six-and-a-half years for espionage.

Hantsom is currently serving time in prison. He could not be reached for comment. All other saboteurs received suspended sentences. Factors influencing the legal outcome included plea deals and cooperation with the investigation. Russin, Nesterenko, and Malanskas did not respond to inquiries, and The Insider was unable to establish contact with Mussayev.

When contacted by The Insider, Kolomainen, who had admitted guilt in court, denied orchestrating the scheme. He claimed to have accepted a plea deal solely to focus on running his construction business, insisting his only mistake was that he “didn’t snitch” about the plan. He also noted that the court case was classified as closed.

“I was told to keep my mouth shut, so I’m keeping my mouth shut,” he said. Hantsom's GRU contacts, Alik Huchbarov and Ilya Bocharov, have been declared internationally wanted. As of Dec. 2, they were unaware of their status.

The Insider refrained from contacting Alik Huchbarov and Ilya Bocharov, as requested, to avoid alerting them to their wanted status ahead of a KAPO press conference scheduled for December 5. Both are hiding somewhere in Russia, beyond the reach of Estonian authorities — unless, of course, Huchbarov decides to flash his Estonian passport at border crossings and come back.

“Some time after the incident,” Läänemets, the Estonian Interior Minister, told The Insider, referring to the vandalism of his vehicle, “we had a routine meeting of the interior ministers of the states along the eastern border. I informed them about the case. The predominant reaction was surprise: surprise that the Russians were targeting individuals at such a high level.”

“Yes, it’s just a car,”Läänemets continued, “but as a signal, it’s something much bigger. Essentially, this amounts to the Russian government ordering an attack on the Estonian government.”