The Pervy Otdel (Dept.One) human rights group has reported the infection of Russian antiwar activists' devices with Monokle — a spyware tool developed by the St. Petersburg-based Special Technology Center (STC). This is the first case in which human rights activists learned of the use of this software against Russians who oppose the war in Ukraine.

Monokle is a malware tool that provides its operator with remote access to Android phones. The remote access trojan (RAT) allows its user to read messages, make screen recordings, listen in to calls, track the victim's movements, download files from the infected device, and browse the passwords stored on it. The spyware is hidden in the victim's phone under the guise of ordinary applications.

That's exactly what happened to Kirill Parubets, an IT professional who reached out to Pervy Otdel for help. Looking into his case, the human rights activists learned more about how this tool works.

How Kirill Parubets's phone was infected

Kirill Parubets is a mathematician and systems programmer. An ethnic Ukrainian, he was born in Moscow and graduated from the Moscow Aviation Institute. In 2020, Kirill and his wife Lyubov moved to Kyiv. In Ukraine, Parubets worked in IT as a system business analyst and volunteered for humanitarian projects even before the full-scale war started, helping Donbas residents receive medical supplies, groceries, and other necessities.

The beginning of the full-scale war caught the couple in Georgia, on vacation, and Kirill continued volunteering for several charities while remaining abroad. In the summer of 2022, he returned to Kyiv to help Ukrainians affected by the fighting. However, the war had made it almost impossible for a Russian national to extend his residence permit in Ukraine. Kirill decided to apply for citizenship in Moldova and then Romania, where he has roots. For that, he needed to return to Russia and prepare the necessary paperwork. The couple entered the country without incident through the land border with Georgia and began gathering documents.

On Apr. 18, 2024, six masked men with automatic rifles burst into the couple's Moscow apartment and put them face down on the floor in different rooms. The first question they asked Kirill was: “Did you send money to Ukrainians?” They made him do squats and beat him if he stopped. They threatened him with life imprisonment and even summary execution. The law enforcement agents collected all electronic devices and papers in the apartment, knowing exactly where to find them.

“I had the impression that they had been to our place before or had bugged it: very quickly, for one, they quickly found the laptop, although it was not on the table with the phone. They also found papers related to Ukraine almost instantly. They demanded my phone password, and when I refused to give it up, they started beating us. My wife was 'stomped on with boots,' as she later told me. It was terrifying,” Kirill recalls.

After that, the officers signed a report and took the detainees to the police station. There, they were forced to write a “confession” that they had “violated public order in a public space.” They were then taken to a detention facility. A week later, Kirill was ordered out of his cell for a conversation with two “men in black suits with black suitcases.” He was shown a large, 10-centimeter-thick folder with printouts of his correspondence.

Kirill was purportedly suspected of state treason, a crime punishable by a prison sentence ranging from 12 years to life. The agents also said they were very interested in Kirill's friend Ivan (name changed), who was suspected of the same crime. He was offered a choice: either he and Ivan would both go to jail for treason, or he would “cooperate” and report on everything Ivan had done and said. The declared objective was to neutralize “highly dangerous Ukrainian criminals” with whom Ivan communicated. Kirill agreed to cooperate. A few days later, he had before him a “cooperation and non-disclosure agreement.”

After 15 days of arrest, the couple was released. They were subsequently called to Lubyanka to receive an assignment. Kirill was supposed to wait for Ivan to get in touch, casually ask him if he had any jobs that needed doing, and report everything to the security agency. Kirill got his devices back but was in no hurry to use them, deciding to check for spyware first. It was not long before he found what he was looking for.

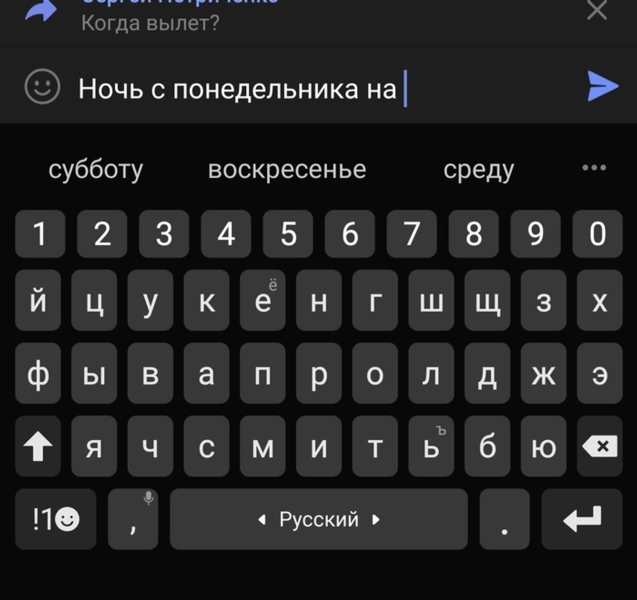

“Naturally, I checked all the devices. I found a weird program on my phone. I got an obscure notification on the notification panel — something like 'ARM Cortex,' which is the name of a series of processors for Android devices. I started digging and found a suspicious system application with the same name and a mind-boggling amount of permissions. I extracted the file, uploaded it to VirusTotal, and checked it for viruses, but it came out clean.

Luckily, the service has a sandbox, where you can see what an app does. And I saw that the app has a call recording feature and geolocation detection. Digging into the app further, I looked at the code and realized it was some kind of spyware. I instantly alerted several antivirus vendors about this file. As a cybersecurity enthusiast, I'd read about the discovery of the Monokle spyware module in 2019, and my app was very similar in description and behavior.”

Soon Kirill and his wife got out of Russia — fortuitously, he had made a second passport in advance. His wife obtained a second passport after being released from custody. Evidently, her access to public services was not as interesting to the security agencies as her husband's.

What we know about Monokle

The first reports of the Monokle trojan emerged around 2018. In 2019, the mobile security vendor Lookout released a report on the malware tool, indicating that its developer is the St. Petersburg-based Special Technology Center. The company came under U.S. sanctions back in 2016, but under EU sanctions only in 2023. The sanctions against STC were initially linked to its alleged collaboration with Russia's Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU) and complicity in meddling in the 2016 U.S. election. STC was also known to supply drones, network coverage suppressors, and other specialized electronic equipment to the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the FSB, and other Russian government agencies. Many STC employees, including CEO Alexander Mityanin, graduated from the Budyonny Military Academy of Communications in St. Petersburg.

As Lookout highlighted in its 2019 report, Monokle not only bears the distinctive features of spyware — it also has additional functionality that enhances its efficiency. For instance, the program infiltrates predictive text dictionaries, a feature that helps the program operator better understand the victim's interests.

Another use case proving that Monokle is designed for targeted attacks is its behavior when the phone screen is locked. Monokle can record the screen to track the moment when the victim unlocks the device, allowing remote access users to find out the PIN code, graphical key, or password. Lookout experts found that the trojan developers enabled the virus to steal the victim's data even without root access to the phone.

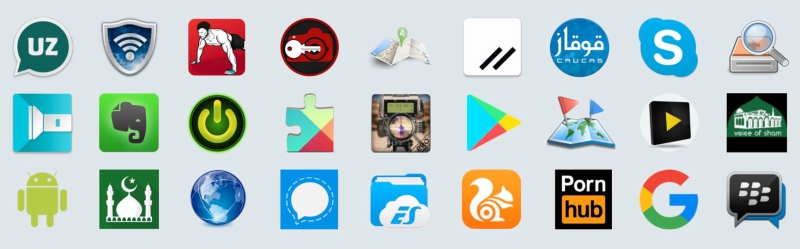

Monokle is installed on the victim's phone as part of another program that pretends to be legitimate. Back in 2019, Lookout gave examples of such programs: most were in English, but some were also available in Russian and Arabic. In particular, Monokle posed as Evernote, PornHub, a workout app, or a messenger, and usually even offered corresponding functionality.

As far back as 2019, experts identified the following groups as potential Monokle targets:

- Those interested in Islam

- Residents of the Caucasus

- Those interested in joining the Ahrar al-Sham Brigades fighting against the Syrian Arab Army and the government of Bashar al-Assad

- Users of UzbekChat, a Telegram-based messenger.

Lookout experts emphasized that Monokle could be used to target other groups as well. In the case of the groups listed above, the targeted attack focused on specific interests: users would download an infected application from the Internet and install it on their phones, thus enabling surveillance of their activities.

When Kirill Parubets turned to human rights activists for help, they analyzed the application that appeared on his phone after the search. Together with Toronto-based Citizen Lab — the team that exposed Pegasus spyware — Pervy Otdel concluded that the app is most likely an updated Monokle trojan.

How to tell if your device is infected

As Pervy Otdel told The Insider, only Android devices are known to be susceptible. However, researcher Cooper Quintin told Citizen Lab in a Pervy Otdel video that the possibility of infecting an iOS device has not been ruled out. Back in 2019, experts discovered that Monokle featured unused commands, suggesting the existence of an iOS version. The program performs most of its actions via Android Accessibility Services. These services were designed to make it easier for people with disabilities to use mobile devices — for instance, by allowing them to use a smartphone without touching, without voice, and so on.

Attackers can unlock the phone remotely and perform the actions they want while keeping the screen off, meaning the user will not notice that someone is controlling their phone. The server controlling the spyware can send commands to disable or enable geolocation, turn on screen or keystroke recording, turn on or off the camera or microphone, send real-time data to a remote server, download files from the device, or retrieve passwords. In total, Quintin says, Monokle offers a choice of 65 commands.

As a result, the owner of the infected device typically does not know that their hardware is infected — let alone what to do about it. The most reliable sign that your device has been compromised is the fact of its confiscation by the FSB or similar law enforcement agency, Quintin notes. If it has been, this fact is reason enough to show your phone to a cybersecurity expert for a checkup.