Throughout Europe, right-wing politicians are coming to power with promises to fight illegal migration. However, dealing with the issue is more complicated than simply tightening grounds for legal entry. Policies around family reunification, work visas, and asylum for humanitarian and political reasons are all more nuanced than the populists lead their supporters to imagine. Nevertheless, entering European countries is indeed becoming increasingly difficult, and so is the process of gaining naturalization. This does not help combat illegal migration, but it significantly complicates life for those who have lived in a country — often perfectly legally — for many years.

Modern EU migration policy began taking shape during the 2015 refugee crisis, when hundreds of thousands of people from war-torn Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan headed to Europe. Germany accepted more than one million asylum seekers and immediately announced that it was ready to welcome even those who crossed into the EU through another country.

The unofficial motto of the German policy was Chancellor Angela Merkel’s phrase, “We will manage!” Overall, Berlin not only coped with the crisis but did so while integrating two-thirds of migrants into the labor market, partially covering the country’s labor shortage. Later, numerous programs for skilled workers were implemented, including simplified entry procedures for vocational specialists, residence permits for IT workers without diplomas, and the so‑called Chancenkarte — a new type of residence permit that allows for job searching in Germany for up to one year.

Still, the most significant step was reducing the time required to obtain citizenship from eight years down to five — and to three years for those who integrated rapidly enough to speak German at C1 level. In 2024, a record 290,000 people received citizenship.

Although Germany more than managed the crisis, by 2025 by-then-former chancellor Merkel’s policy was being reevaluated, including by members of her own party. Amid inflation and growing dissatisfaction with the domestic state of affairs, right‑wing populist forces — and, later, even many centrists — successfully cast migrants as an internal enemy, an effort that benefited from the support of social media algorithms. Although the migration wave of 2015 peaked a decade ago, 81% of Germans today believe immigration is still too high. Just over 40% call migration the main problem for the economy, and 83% are dissatisfied with the government’s handling of the issue.

Subsidiary protection is a form of international protection granted to people who face serious danger in their home country but do not meet the criteria for refugee status.

By early 2025, then-chancellor Olaf Scholz and his ruling coalition of Social Democrats, Greens, and Liberals agreed on a package of measures intended to accelerate the deportation of refugees. The list of safe countries was expanded, and deportation procedures for convicted foreigners and those denied asylum were simplified.

However, Scholz held off on the harsher steps proposed by opposition leader Friedrich Merz — such as declaring a state of emergency that would have imposed a full entry ban for Syrians and Afghans. Unsurprisingly, earlier this year, further tightening of migration policy became one of the central themes of the CDU/CSU campaign under Merz, who succeeded Scholz as Chancellor in May. At a rally in January, he directly referenced Merkel’s era by arguing that Germany would not cope with the migration flow under its then-current leadership.

After Merz came to power, family reunification was suspended for holders of subsidiary protection. Reforms may affect even refugees from Ukraine, one million of whom were granted temporary protection in 2022. The ruling coalition developed a bill according to which those arriving after April 1, 2025 would have their benefits and subsidies reduced. As of October, the bill had gained interdepartmental approval but had not been adopted.

In addition, the Merz government plans to simplify the procedure for recognizing countries as safe. This will make it possible to deem asylum requests from their citizens unfounded. The goal of this initiative is to reduce the number of applications and speed up deportations.

Subsidiary protection is a form of international protection granted to people who face serious danger in their home country but do not meet the criteria for refugee status.

However, even the current, still unshortened list of countries causes concerns. The most criticized entries are Ghana and Senegal, known for persecution of LGBTQ+ people. There are questions about Georgia due to its government’s increasingly close relationship with Moscow. The family of former Chechen commander Zelimkhan Khangoshvili, who was killed in Berlin by Vadim Krasikov in 2019, was deported to Georgia this past October. They had lived in Germany for almost three years.

Programs for attracting skilled workers have not yet been affected by the new policy. Nevertheless, Germany is second in the EU when it comes to migrant outflow – 67% leave the country in the first five years — behind only the Netherlands. However, the inflow of migrants still exceeds outflow.

A recent study showed that in the last year, 26% of migrants at least thought about leaving Germany. The main reasons they gave for this were bureaucracy, political dissatisfaction, and discrimination. Formally, rules for some migrants are being simplified, but in practice offices are overloaded, and recognizing the qualifications of newcomers takes an extremely long time. Online services also attract criticism — they allow uploading only documents digitized in a special format, which is impossible to do for free. Many format requirements are available only in German.

In 2025, just a year after its introduction, accelerated naturalization in three years was canceled. The decision was largely symbolic, as only 573, mainly in Berlin, had received citizenship this way.

In November, Merz stated that with the end of the civil war in Syria, the grounds for asylum disappear and refugees should return. Those who refuse may be deported in the future. Only a few have a chance to stay under special labor programs. According to recent data, 951,000 Syrians live in Germany.

Subsidiary protection is a form of international protection granted to people who face serious danger in their home country but do not meet the criteria for refugee status.

According to recent data, 951,000 Syrians live in Germany

Despite a significant drop in asylum applications in 2024 and 2025, Germany remains the European leader in the number of asylum seekers. According to UNHCR representative Katharina Totte, Germany’s migration policy has international influence: if Germany closes its doors, it will send a signal to other countries.

According to official data, more than 1.5 million foreigners live in Portugal, and in 2025, a record 387,000 residence permits were issued. However, many decisions were made based on applications submitted before the law had changed.

In recent years, Portugal was one of the most attractive EU countries for relocation and work. Due to an acute labor shortage, the country offered relatively simple legalization tracks for those seeking visas to work in low-skilled jobs.

It also offered a visa for those earning a stable income of 3,480 euros per month and were able to present a remote work contract with a foreign employer. The income of certain highly qualified specialists was taxed at a flat rate of 20%, significantly lower than the 53% maximum under the country’s progressive tax scale, and foreigners were exempt from taxation for ten years, a policy that made Portugal extremely popular among digital nomads.

The most common pathway to residency went through Manifestação de Interesse (MI), which allowed even those who had entered Portugal on a tourist visa to legalize an extended stay. In practice, a foreigner could enter the country without a job offer and look for work locally.

The required documents were relatively modest: a work contract or proof of self‑employment, social security contribution data, a rental agreement, a bank statement, and insurance. While documents were being reviewed, applicants could legally reside and sometimes even legally work in Portugal. Hundreds of thousands followed this route, overloading the system. The backlog for interviews with MI grew to several months, and in some cases, even years.

Another incentive was the possibility to apply for citizenship after only five years of residence, with the countdown starting not from the residence permit issuance date, but from the application date. Additionally, a child born in Portugal to foreigners who had lived in the country for at least one year receives citizenship by birth (even if the path for the parents is more arduous).

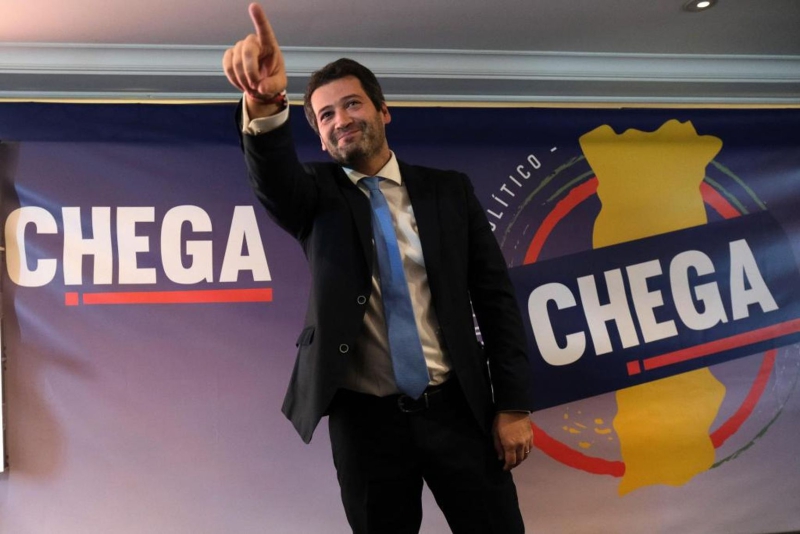

However, when Luís Montenegro’s right‑of‑center Democratic Alliance (PSD, CDS‑PP, PPM) came to power this past May (accompanied by the strengthening of the far‑right Chega party), migration policy became much stricter. The residence requirement for citizenship was increased to ten years, and the start date now counts from the moment of residence permit issuance. Naturalization requirements were also toughened: applicants must know Portuguese at a basic level and pass a cultural‑civic test. The same integration requirements were introduced for family reunification permits. In addition, visa routes for job search (Manifestação de Interesse) and the preferential tax regime for most nomads were abolished. Applicants for temporary visas, including work visas, must now present a return ticket.

These measures represent the Democratic Alliance’s attempt to take the agenda from Chega — now the main opposition force. Analysts believe Prime Minister Montenegro is trying to satisfy the far‑right without entering into a formal coalition.

The crackdown will have very real negative consequences for the Portuguese economy. Population aging and outflow (up to 70,000 people annually) mean demand for labor in the country remains high, but now a much higher portion of migrants will simply work in the gray sector. Authorities justify the reforms as an attempt to make migration regulated and aligned with economic needs. but it is unclear how extending citizenship waiting times or removing tax benefits solves this issue.

Subsidiary protection is a form of international protection granted to people who face serious danger in their home country but do not meet the criteria for refugee status.

Some migrants from Russia call the new laws politically motivated. The abrupt transition to new procedures ruined long‑term plans for thousands of Russians while barely improving migration processes. Still, even with restrictions, Portugal remains attractive to Russian migrants, and they are not in a hurry to leave.

«Here the weather is good, housing prices are comparable to other European capitals, and food is significantly cheaper than in Germany, France, or Northern Europe,» says Nikolai, a restaurateur who moved to Portugal. «Therefore, I plan to live here and apply for permanent residence in five years and citizenship in eight.»

Some are still planning to settle in Portugal despite the changes to the immigration regime. «Even before, no one received citizenship in five years,» explains Yevgeniya, an HR specialist, who moved to Portugal from Montenegro this past May. «Everything is very bureaucratic, the migration system cannot cope. People who have lived here for two or three years and pay taxes as private entrepreneurs still have no residence permit. People live for many years and cannot even register with the Agency for Integration, Migration, and Asylum.»

As of November 2025, the law has been adopted by parliament but has not entered into force, as it awaits a Constitutional Court review. Until a decision is made, the old rules remain in place — but no one knows for how long. In Portugal, as usual, no one is in a hurry.

Migration policy in the Netherlands has always been particularly strict, even by EU standards. In the mid‑2000s, those applying through the “family” channel were required to pass a pre‑entry integration exam, which included Dutch language and history tests.

The exam became widely known thanks to a film that migrants were required to watch in order to assess whether they were ready for the country’s culture. The video showed urban slums where, according to the voice‑over, poor migrants from Turkey and Morocco lived.

Subsidiary protection is a form of international protection granted to people who face serious danger in their home country but do not meet the criteria for refugee status.

The video, among other things, showed urban slums where, according to the voice‑over, poor migrants from Turkey and Morocco lived

It is important to note that EU and Swiss citizens were exempt from exams, and the measure was criticized by Human Rights Watch shortly after its adoption.

Until 2010, the Netherlands made a distinction between family reunification and family formation. In the first case, the marriage was concluded before the foreign partner entered the country; in the second – after arrival. In cases of family formation, an income threshold of 120% of the minimum wage was set for the Dutch partner in order to ensure that the family would not need social assistance.

In practice, this threshold was unattainably high for many young specialists and automatically closed entry to many. It was abolished only after a European Court decision clarified that countries may take measures to ensure that potential migrants will not become a burden on taxpayers, but they have no right to set an excessively high financial barrier.

In 2015, amidst the large influx of refugees, the government of then-prime minister Mark Rutte called for depriving refused asylum seekers of food and shelter if they did not leave the country. Despite criticism from the UN and the European Committee of Social Rights, the Supreme Court allowed this measure to stand.

In subsequent years, the Netherlands continued working on accelerating procedures, but not on humanizing them. After 2015, the number of refugee accommodation centers was reduced, and attempts to open new ones encountered resistance from local residents. This resulted in an acute shortage of places and, in 2022, a large‑scale crisis.

Ter Apel camp, the main asylum reception point in the Netherlands, became the symbol of that crisis. Due to lack of space and staff, refugees slept in overcrowded halls — and, often, outdoors.

Subsidiary protection is a form of international protection granted to people who face serious danger in their home country but do not meet the criteria for refugee status.

Authorities could not cope with the flow and transferred people to other centers, only to return them the next day to Ter Apel. In addition, police stopped volunteers who attempted to help refugees.

The situation made international headlines, especially after the death of a three‑month‑old infant. Asylum seekers could not receive basic medical assistance, so Doctors Without Borders began providing it — the first time the organization had worked in a wealthy European country.

Rutte stated at the time that he was ashamed of what was happening. His government announced a set of anti‑crisis measures, though in practice, its main action involved delaying family reunification for those who had not already secured appropriate housing.

Subsidiary protection is a form of international protection granted to people who face serious danger in their home country but do not meet the criteria for refugee status.

Prime Minister Mark Rutte stated he was ashamed of what was happening with the migrants

The Netherlands Institute for Human Rights criticized the measure and later recognized it as non‑compliant with EU law. The government could not reach a consensus on migration policy, and in 2023 Rutte submitted the resignation of his entire cabinet.

In the 2023 elections, the far‑right Party for Freedom, led by the notoriously Islamophobic Geert Wilders, won a plurality and succeeded in forming a coalition, although the post of prime minister was given to a compromise figure — centrist Dick Schoof.

Before the elections, Wilders softened his most odious proposals, but his migration agenda remains the strictest not only in the history of the Netherlands, but in the entire EU. According to the program, the Netherlands should stop accepting asylum seekers, freeze family reunification, accelerate deportations, and use the army to guard national borders.

The package is intended not only to stop refugee inflows, but also to make legal migration significantly more difficult. Wilders proposed tightening naturalization rules (Dutch level B1, extending citizenship waiting period from 5 to 10 years), introducing quotas for international students, and restricting the inflow of low‑skilled labor. As a result, in the summer of 2025 the coalition collapsed, and Dick Schoof resigned. In the October elections, Wilders’ Party for Freedom party and the liberal D66, led by Rob Jetten, won 26 seats each.

However, since D66 outpaced the Party for Freedom by 30,000 votes, it is the one forming a new coalition. Experts believe that D66 will move toward normalization and operate within the framework of the EU Migration Pact.

Overall, the previous coalition fulfilled only around a third of its promises, with another third remaining stalled in the Senate. The fate of these measures will determine where Dutch migration policy moves next.

Finland’s migration policy has never been considered soft. Still, all the way back in 2003, authorities allowed for dual citizenship, and in 2011 the naturalization period was reduced to five years of continuous residence (or seven when accounting for temporary absence). In exceptional cases, it was possible to obtain citizenship in four years.

In 2012, the country launched the Future of Migration program, which focused on targeted labor migration, individual integration plans, and the quick but thorough processing of asylum applications. However, the 2015 migration crisis forced a reconsideration.

Finland was not ready for the influx — 32,000 asylum applications were submitted, compared to 3,600 one year earlier. This led to an urgent expansion of border services and the deployment of hundreds of reception centers. Prime Minister Juha Sipilä called on Finns to help refugees and even offered his own home for accommodation. However, he later withdrew the offer, citing security concerns.

Subsidiary protection is a form of international protection granted to people who face serious danger in their home country but do not meet the criteria for refugee status.

Finland was not ready for the influx — 32,000 asylum applications were submitted compared to 3,600 one year earlier

To control the flow, in 2016 the government approved an 80-point plan. In it, humanitarian protection was abolished, cancelling programs that had previously issued residence permits to those who did not qualify as refugees but could not be returned home due to danger. The move significantly affected people from Somalia and Iraq.

As part of the new strategy, access to state legal aid was reduced, and appeal deadlines were shortened. The income threshold for family reunification was raised to 1,700 euros after taxes, which experts considered unreachable even for many Finns.

In 2023, with the accession of the right‑center coalition led by Petteri Orpo, a broad campaign began against illegal migration, further affecting legal channels as well. The right‑populist Finns Party, whose representatives received key cabinet positions including the Ministry of Finance, played an important role. Their anti‑immigration policy is largely explained economically: “A welfare state and open borders are incompatible.”

In 2026, new naturalization requirements are set to come into force. Applicants will be required to be completely financially self‑sufficient, and the receipt of social benefits, including unemployment benefits, will be allowed for no longer than three months. A shortened limit was also set for job searches for those seeking to retain their work visa after a dismissal, and the salary threshold for obtaining one was increased to 1,600 euros (after the Finns Party proposed raising it to 3,000 euros).

In addition, applicants for citizenship must have a perfectly clean criminal record. Even a parking fine can postpone the opportunity to apply for citizenship for several years. At the same time, the naturalization period increased from five to eight years, and the period of continuous residence required for permanent residency is planned to increase from four to six years.

The main argument for such strict measures is the escalation on the border with Russia. Russia’s security services have used migration as a means of putting hybrid pressure on Finland. In 2023, hundreds of refugees from Syria, Somalia, and Yemen appeared on the Russian‑Finnish border, and Russian border guards not only did not stop them, but sold them bicycles and sent them over to the Finnish side.

To prevent a repeat, by the summer of 2025 Finland built the first 35 kilometers of a fence on the border with Russia, with plans to extend its length to around 200 kilometers. Even so, it will cover only a small part of the border and is not a defensive structure — the mesh can stop only refugees, not military vehicles.

Subsidiary protection is a form of international protection granted to people who face serious danger in their home country but do not meet the criteria for refugee status.

Professor of border studies Jussi Laine harshly criticized the initiative. He expressed concern that during a crisis, people who truly need protection and have the right to receive help may be trapped behind the fence. Earlier, Amnesty International also stated that such measures seriously infringe upon the right to asylum.

According to surveys, 65% of Finland’s one‑hundred‑thousand strong Russian‑speaking population said that state actions on the eastern border reduced their feeling of security. Cultura Foundation expert Eilina Gusatinskaya noted that Russian‑speakers perceive the border closure very personally and believe that this measure is directed against them.

Those who still have ties with Russia are forced to get there by traveling through Norway or Estonia. One respondent told Finnish media outlet Yle that he is most afraid that, in an emergency, his mother, who lives in Petrozavodsk, may die before he has the chance to reach her. Because of the closed borders, the road from Joensuu, where he lives with his family, now takes three days and 2,700 km.

The cases outlined above are far from outliers. Throughout the Western world, there is a trend toward tightening migration policy. The United Kingdom and New Zealand restricted labor migration by raising income thresholds. Hungary introduced limited “guest visas” for certain specialists from a select number of countries. Austria took a step conflicting with EU rules by temporarily suspending family reunification, and the government in Vienna is preparing a new package of migration restrictions. Montenegro, striving for EU membership, significantly raised the threshold for a residence permit based on real estate and complicated life for private entrepreneurs.

Some of the measures taken by European countries are understandable — for example, those that are clearly related to Russia’s ongoing destabilization efforts, which forces countries to take increased security measures. But others raise concerns, appearing more like an attempt to replace the fight against illegal immigration by creating excessive difficulties for legal migrants. Most importantly though, right‑wing populists are blurring the boundaries between legal and illegal, potentially depriving European economies of much-needed labor while making the lives of those seeking new opportunities abroad even harder.

Subsidiary protection is a form of international protection granted to people who face serious danger in their home country but do not meet the criteria for refugee status.