Russia is preparing a bill to ban the “childfree ideology.” At the St. Petersburg International Legal Forum in June, Russian Deputy Minister of Justice Vsevolod Vukolov, one of the project’s authors, described the conscious decision not to have children as “extremist-oriented.” This followed from the messaging in Vladimir Putin’s latest May decree, which included an increased birth rate among Russia’s “national development goals.” The stated aim is to raise the average number of children per woman from the current 1.41 to 1.6 by 2030 and to 1.8 by 2036. Of course, the issue of a low total fertility rate (TFR) is not unique to Russia. By 2050, only 49 countries are expected to have a TFR sufficient for population replacement, and there is not a single country in the world where the 2021 birth rate had not fallen below its 1950 figure. Decrees alone will not solve this problem, and modern research indicates that not even drastic state measures, such as banning contraception and abortions, can reverse the trend.

Like the issues of global warming and the depletion of fossil fuel reserves, the worldwide decline in birth rates is often a subject of alarmist discussions. Not all that long ago, the opposite was true: the overpopulation of the planet, which 18th century English demographer and economist Thomas Malthus predicted would imminently lead to universal famine, gave way to two centuries of apocalyptic “Malthusian” expectations. These peaked in the 1960s and 1970s, when the world's population was indeed growing at an alarming rate. At the time, scientists themselves recognized the issue and provided a mathematical basis for the alarm. In 1960, Austrian physicist and mathematician Heinz von Foerster and his colleagues published an article in Science with the provocative title, “Doomsday: Friday, 13 November, A.D. 2026. At this date human population will approach infinity if it grows as it has grown in the last two millennia.”

“Doomsday: Friday, 13 November, A.D. 2026. At this date human population will approach infinity if it grows as it has grown in the last two millennia”

In the article, the scientific authorities demonstrated that the growth of Earth's population from the Roman Empire to 1958 could be accurately described by a hyperbolic model. Unlike exponential population growth, in which the growth rate is proportional to the population, hyperbolic growth means the rate is proportional to the square of the population. This results in slow initial growth that rapidly accelerates towards infinity. If this trend had continued, the Earth's population would indeed have become infinite by 2026.

However, scientists understood that this was merely an interesting mathematical exercise, not a serious prediction. It was impossible under any circumstances, primarily because there is a biological limit to the rate of reproduction for any living organisms — humans included. But despite the clearly unrealistic nature of such forecasts, alarmist interpretations of these scientific publications and expectations of a Malthusian apocalypse persisted.

In fact, the hyperbolic growth identified by von Foerster ceased around the time it was discovered. The peak population growth rate of 2.3% per year was reached in 1963. After several years of fluctuating around this level, the growth rate began to decline. Today, it stands at approximately 0.9% per year.

The peak population growth rate of 2.3% per year was reached in 1963. Today it stands at approximately 0.9% per year

Modern demographic models are more reliable than climate models. Based on forecasts that have already materialized, they have been shown to accurately predict future trends. According to these models, population growth will cross the zero mark in the 2080s. After peaking at 10.4 billion, the global population will stop growing and will begin to slowly decline by the end of this century. What happens after 2100 remains uncertain.

At this point, we enter a demographic “terra incognita,” where current patterns cannot be reliably extrapolated. By the end of the century, most societies will have reached a stage of demographic development that only a few developed countries have so far experienced: low mortality, high life expectancy, a high proportion of elderly people, and low birth rates. Scientists therefore still lack sufficient data to understand the general behavior patterns of societies at this advanced stage of demographic development.

But no matter how successful science becomes or how accurate forecasts prove to be, demographic alarmism remains persistent, even if its focus has shifted. During Heinz von Foerster's time, the fear was overpopulation; today, it is depopulation. On March 20, 2024, the prestigious scientific journal The Lancet published the results of a comprehensive analysis of fertility data from 204 countries between 1950 and 2021, extending the forecast to 2100.

The findings of this study reaffirm what has become increasingly evident: fertility rates are declining worldwide. In every country across the globe, fertility rates have decreased across the period in question. This decline has occurred even in regions like Singapore, where the authorities have made significant efforts to reverse it. And yet, despite strong stimulation efforts since the mid-1980s, fertility saw only slight, temporary growth before continuing to decline.

In every country across the globe, fertility rates decreased between 1950 and 2021.

Of course, regional and country specific difference of degree are visible in the overall trend. In the “economic tigers” of Southeast Asia — South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan — fertility has declined rapidly and significantly, plummeting from 4.5-6.8 to 0.9-1.1 over the span of 70 years, leaving it well below the replacement threshold conventionally set at 2.1.

In affluent European nations such as France, the United Kingdom, and Sweden — where fertility was already low in 1950 — there has been a less pronounced decrease: from 2.2-2.8 to 1.5-1.8. Eastern European countries like Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania have experienced a slightly sharper decline, with fertility dropping from 2.4-3.0 to 1.1-1.5. And in more economically disadvantaged African countries — Niger, Chad, and Mali — the decline has been minimal: from 7.3-7.6 to 6.2-7.0.

Globally, fertility rates fell from 4.8 to 2.2. While in 1950 fertility was above the reproduction level (2.1) almost everywhere, by 2021 only 46% of the world's countries (94 out of 204) were still above this threshold. Half of these are sub-Saharan African states.

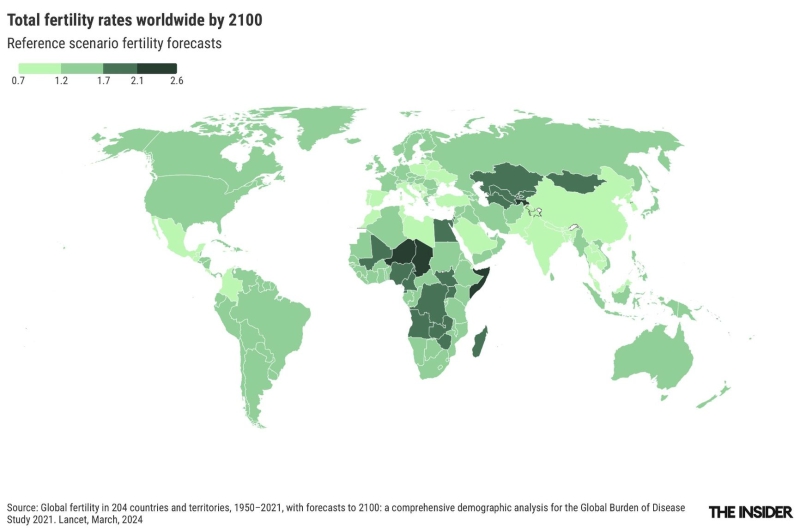

By 2050, the average global fertility rate is projected to decline to 1.8, leaving only 49 countries (24%) with fertility rates above the 2.1 replacement level. Looking ahead to 2100, these numbers are expected to further decrease — to 1.6 and 6 countries (2.9%), respectively. Although forcasts on such a time horizon are less reliable, the six states expected to be the last to join the sub-replacement group are Somalia, Niger, Chad, Tajikistan, and the two small island states Tonga and Samoa.

By 2100, Somalia, Niger, Chad, Tajikistan, Tonga, and Samoa are expectedto be the remaining countries capable of sustaining their population size

The decline in fertility is an inevitable feature of a specific phase known as the “demographic transition.” Every country experiences this transition at varying times and speeds.

In pre-industrial societies, high fertility rates — typically around 6-8 children per woman — coupled with high mortality, low life expectancy, poverty, and widespread illiteracy, characterized life for the majority of the population. Humanity endured in such a state of scarcity throughout much of its history. Periodically, technological or cultural advancements emerged, enabling increased food production. However, improvements in living standards were minimal as these gains were primarily directed towards sustaining growing populations rather than enhancing their quality of life.

Throughout much of human history, advancements and innovations primarily served to facilitate population growth rather than to improve living standards

The population grew slowly alongside the gradual development of technologies that expanded the Earth's “carrying capacity,” enabling more people to be sustained at the same old minimal levels of material prosperity. This societal state, in which sluggish population growth consumed all the benefits of innovations, leaving people impoverished, undernourished, and lacking education, is known as the “Malthusian trap.” At one time, it appeared to be the only conceivable scenario for our existence.

This was Thomas Malthus's view when he articulated it in the late 18th century. Malthus believed that poverty was inevitable due to the fact that any improvements in living conditions prompted accelerated reproduction and/or reduced mortality rates among the population. This, in turn, led to further population growth, causing conditions to deteriorate once more. As a result, society remained entrenched in poverty and ignorance, even as technological progress advanced (albeit at a pace that appears decidedly sluggish when measured against today’s rate of development).

Then humanity discovered a way to escape the Malthusian trap. Like von Foerster, Malthus accurately described a longstanding demographic development just as it was coming to an end. First in England at the end of the 17th century, and subsequently in other Western European countries during the 18th century, growth in production began to ever so slightly outpace population growth. This marked the onset of the Industrial Revolution, in which an industrial society’s median standard of living, after prolonged stagnation, abruptly began to rise. Positive feedback loops were activated, sustaining this upward trajectory. Literacy rates increased, scientific and technological advancements accelerated, further boosting production and living standards. Even though people continued to reproduce vigorously (in line with Malthus's theory), their efforts could no longer match the pace of economic growth, allowing progress to advance at an accelerating rate.

The solution to issues like hunger, state-sponsored welfare for the vulnerable, and advancements in hygiene and medicine naturally led to a significant decline in mortality rates, including infant and child mortality. This marked the beginning of a demographic boom: mortality had plummeted to unprecedentedly low levels, while fertility remained at the typical “pre-industrial” rate of 5-7 children per woman. Countries entering this phase of demographic transition experienced rapid population growth.

Today, nearly all countries, even the least economically developed ones, have reached this demographic stage. Unlike in the past, doing so does not require a domestic industrial revolution or the extensive development of education and science. Instead, simply cooperating with wealthy nations to ensure the adequate supply of food, medicines, and essential goods, along with support in establishing healthcare systems, leads to a sharp decline in mortality and a subsequent population growth.

However, population growth cannot continue indefinitely. While the timing varies by country, after a decline in mortality rates, a decrease in fertility inevitably follows. Numerous studies have highlighted that one of the most influential factors in this development is women's education. This is evident from cross-cultural comparisons demonstrating that the level of female literacy consistently emerges as one of the strongest predictors of fertility rates in a country.

Women's education stands is a critical factor contributing to the decline in fertility rates

In addition, comparative studies within populations consistently show that educated women tend to have fewer children. This conclusion is reinforced by specialized studies aimed at establishing causal relationships rather than observing mere correlations. In controlled settings, multiple studies have demonstrated that women's education directly influences lower fertility rates — not the other way around.

This makes sense, as education provides women with life opportunities that are easier to pursue when not constrained by all consuming amounts of children. Traditionally, having a large family might have conferred a certain social status on the mother, but for a woman aspiring to the career of doctor, engineer, banker, or diplomat, it does not. Moreover, educated women typically adopt a more take-control approach to planning their lives and ensuring the health and well-being of their current and future children. These factors collectively reduce the desire among educated women to have larger families.

Other significant factors include the availability of contraceptives and the diminishing economic benefits of childbearing. In agrarian societies, children are often considered capital, whereas in industrialized societies, they are viewed more as expenses. With drastically reduced mortality rates, societal values have shifted towards placing higher importance on human life and the responsibility of parents towards their children. As a society becomes more prosperous, a cultural shift often occurs by which it becomes less fashionable and prestigious to have large families. As a result, more people are delaying parenthood to pursue careers in order to ensure that the children they do bring into the world are provided with decent living conditions.

Advanced Western countries entered this phase of demographic transition in the early 20th century, and now most of the world is following suit. This global trend explains the decline in fertility rates. Even in the least developed countries, average living standards are higher than they were just a few decades ago, and signs of this global trend are becoming apparent there as well.

But regardless of a society's achievements in prolonging life or reducing mortality rates, once fertility drops below replacement level, the native born population begins to decline.

According to the Russian federal state statistics service Rosstat, in 2023 Russia's total fertility rate dropped to 1.41. Recently, Vladimir Putin issued directives aiming to raise the TFR to 1.6 by 2030 and 1.8 by 2036. This goal is relatively modest: Putin's plan does not even target returning the population to the replacement threshold. But is it achievable?

In theory, yes. Putin's plan, in terms of both scale and timeline, falls within the realm of minor and largely random fluctuations observed in individual countries undergoing a broader, long-term decline in fertility rates. The chances of effecting a successful increase in TFR could improve with a well-coordinated set of measures to encourage childbearing. However, even if the target is met, it will halt Russia's population decline.

Based on the unsuccessful attempts of other countries, it appears humanity has yet to discover a reliable means of reversing declining fertility rates. Measures that may seem straightforward to policymakers and social workers — such as comprehensive support for families with children, promoting childbearing, assisting economically disadvantaged groups, facilitating educational access for children from large families, and so on — typically yield nothing more than modest, short-term effects.

Extreme measures such as a complete ban on contraception and abortions, or even the imposition of religious laws promoting childbearing, have proven ineffective. While such measures may occasionally yield results within small religious communities or cults, they have generally failed on the scale of larger states.

While radical measures to increase fertility may yield results within small religious communities or cults, they have generally failed on the scale of larger states

Even in Iran, fertility has plummeted from 6.2 to 1.5 over the 1950-2021 period, with the sharpest decline occurring after the onset of the 1979 Islamic Revolution. A similar trend is observed in Saudi Arabia and other predominantly Muslim countries. North Korea has also been unable to avoid this global trend: over the period in question, fertility there declined from 5.4 to 1.5 children per woman.

The case of Afghanistan is noteworthy. The Taliban government, which came back to power in 2021, is attempting to enforce a complete ban on women's education. Such a step could theoretically increase fertility, particularly since TFR in the country was already above four children per woman and women's education levels were extremely low even before the Taliban's return. However, thus far there has been no visible effect. Instead, fertility in Afghanistan continues to decrease and currently stands at around 3.75. It is likely that for such measures to have an impact, a generation of marginalized, uneducated women would need to grow up. Hopefully, these extremist policies will not endure for that long.

Perhaps these extreme methods fail because even the most anti-human regimes and fanatical dictators cannot reverse societal progress to the extent that educated city dwellers are transformed into illiterate peasants. Pol Pot attempted such a policy in Cambodia but did not achieve complete success: fertility there declined from 6.6 to 2.6 children per woman over 70 years, a change not significantly different from that in Laos and Myanmar. In contrast, Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam have experienced even sharper declines, from 6.7-6.9 to 1.3-2.1 children per woman.

Generally, the better life becomes in a country, the more rapidly fertility declines. Conversely, in countries with lower standards of living, fertility decreases more slowly. Of course, intriguing exceptions do exist. In Israel, fertility remains relatively high and its decline is notably gradual given the country’s high overall quality of life. Clearly however, such outliers are neither large nor numerous enough to meaningfully alter the overall pattern.

The better life becomes in a country, the more rapidly fertility declines

Demographic modeling indicates that the prospects of significantly slowing down the decline in fertility are scarce. For instance, the aforementioned article in The Lancet outlines four alternative scenarios. The baseline model assumes societies will progress along their current trajectories. According to this model, by 2050 the global average fertility rate will be 1.83, decreasing to 1.59 by 2100.

The first alternative scenario envisions the ambitious implementation of UN plans for global education development, including in the poorest and most underdeveloped regions. This would likely accelerate the decline in fertility, yielding a TFR of 1.65 in 2050 and 1.56 in 2100.

A second scenario imagines universal access to contraceptives for all who desire them worldwide (though this remains a distant aspiration unlikely to materialize fully). Under this scenario, fertility rates could drop to 1.64 in 2050 and 1.52 in 2100.

If societies around the globe were to maximize support for families with children and create optimal conditions for reproduction, the projections suggest fertility rates might rise to around 1.93 and 1.68, respectively — still significantly below the replacement level.

In short, it appears increasingly unlikely that the global decline in fertility can be halted, regardless of whether action is attempted at a global scale or within individual countries. International organizations like the UN or WHO, democracies, theocracies, and authoritarian regimes alike are all unlikely to effectively address this challenge. The trajectory of declining fertility seems inevitable, with adjustments in its pace possible only within a narrow margin.

It appears unlikely that the global decline in fertility can be halted, whether at a global scale or within individual countries

The implications of the global decline in birth rates raise significant questions about future societal changes. Population aging presents a formidable challenge. The increasing proportion of elderly people will place greater strain on healthcare systems and on the working-age population, who will bear the responsibility of supporting a larger number of retirees.

Nevertheless, there are factors that may mitigate these challenges. Advances in medicine and overall improvements in living conditions not only extend life expectancy but also enhance the health span of elderly people, who can remain active contributors to society far longer than their parents and grandparents were able to. Additionally, the decline in the proportion of resources allocated to children will partially offset the increase in elderly dependents. Moreover, ongoing technological advancements are expected to reduce the economy's reliance on human labor.

The most significant demographic shifts will occur due to the uneven decline in birth rates across different countries. In prosperous Western nations, population growth has ceased, and in some cases, populations are even shrinking. In Asia, where rapid population growth characterized the latter half of the 20th century, growth rates are now slowing and will begin to decline by the second half of this century.

On this background, sub-Saharan Africa stands out as the only region projected to continue experiencing population growth until 2100. Nearly all global population growth by the century's end is expected to originate from Africa (excluding North Africa, which follows a demographic trajectory more akin to the Middle East). By 2100, every second newborn globally is anticipated to be of African descent, a notable increase from the current ratio of one in four.

By 2100, every second newborn globally is anticipated to be of African descent, a notable increase from the current ratio of one in four

As a result, by 2100, our descendants will inhabit a world with a population approaching 10.4 billion people, distributed as follows: approximately 4.69 billion in Asia, 3.91 billion in Africa, 0.67 billion in North America, 0.59 billion in Europe, and 0.43 billion in South America. To put this in perspective, current population figures stand at approximately: Asia – 4.78 billion, Africa – 1.49 billion, North America – 0.61 billion, Europe – 0.74 billion, South America – 0.44 billion.

Given the anticipated economic growth and the prospect for socio-cultural advances in less developed regions, these shifting demographic proportions will likely enhance their influence across various domains: economic, cultural, scientific, and military. This transformation could be further accelerated by substantial migration flows from high-birth-rate, poorer countries to low-birth-rate, wealthier ones, where population growth rates have already fallen below replacement levels.

It is here that the question arises: will modern “Western” ideals such as freedom and democracy, gender and other equalities, concern for environmental issues, and belief in the power of science manage to capture the minds of those societies that will dominate global population statistics in 50-100 years? Until recently, the export of Western ideals seemed to spread around the world along with smartphones, McDonald's, and rising prosperity. This process was fueled by the universal recognition that Western countries are the “most advanced,” but whether this trend is also irreversible remains a matter of debate.

Demographic trends are indeed steering the world towards significant transformations. However, the issue lies not just in the global decline in birth rates or the eventual end of population growth (an eventuality that remains some 60 or so years in the future). The primary challenges will stem from the starkly uneven distribution of this decline across countries and regions — particularly the higher birth rates expected in less developed regions, where quality of life remains relatively lower. Overpopulation in these disadvantaged stretches of the globe, juxtaposed with relative underpopulation in wealthy and prosperous areas, could lead to social tensions that may continue to intensify until the end of the century. Nevertheless, it is crucial to recognize that this disparity is temporary: by 2100, no region in the world is expected to sustain high birth rates. What happens then is beyond the predictive power of the models.