A girl takes part in an April 2019 demonstration in Kyiv in support of the Ukrainian language, holding a sign that reads, “Please, speak to me in Ukrainian.” Source: UNIAN

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has led — predictably — to a resurgence in enthusiasm for Ukrainian culture and a widespread rejection of all things Russian. In September 2021, around 450,000 Ukrainian students were still studying Russian as part of their formal education — now, there are only 345. The proportion of Ukrainian citizens who speak Ukrainian at home has also markedly grown since the morning when Vladimir Putin’s tanks crossed the border. The Insider spoke both with experts and with ordinary Ukrainians in order to understand how they have seen attitudes toward the Russian language change in recent years.

Putin justified his attack on Ukraine by claiming to be protecting its Russian-speaking residents, but it was Russian aggression that changed the status of the Russian language in the country overnight. Starting from the morning of Feb. 24, 2022, the Russian language began to be widely perceived negatively for the first time. This was despite the fact that Ukrainian society remained predominantly bilingual even in the midst of the Donbas conflict of 2014-2022. For example, back in 2019, 81% of Ukrainians were in favor of teaching Russian in schools, and a quarter of the population spoke Russian at home all the way up until the full-scale invasion.

In 2019, 81% of Ukrainians supported the teaching of Russian in schools, and a quarter of the population spoke Russian at home.

However, in the first months of the war, many Russian-speaking Ukrainians declared their principled switch to Ukrainian (1, 2), and Russian became firmly associated with the the enemy and aggression. As noted by Oscar-nominated film producer Alexander Rodnyansky, “Ukrainian has become one of the most important elements of the cultural code that unites the country.” Rodnyansky continued:

“If you read Ukrainian public posts, you will see a huge number of texts that will tell you the same thing: I used to be Russian-speaking or I only spoke Russian, but today I have switched to Ukrainian, I want to be Ukrainian and speak [my] language, I want to forget Russian or not use it because it is the language of those who came to our country with weapons and are killing people… This is one of the elements uniting this people into a single nation with a shared identity.”

Ukrainian political analyst Volodymyr Fesenko recalls the wave of social media posts that came in direct response to Russian actions:

“I am fairly relaxed about the language issue, but for some people it has become very painful, and attitudes toward the Russian language have deteriorated sharply. For example, my daughter left for Barcelona after the war began, and she and some of her friends switched to Ukrainian on principle.”

The full-scale war completely changed perceptions of both the Russian language and the people of Russia, says Volodymyr Paniotto, president of the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS). Paniotto says that before the start of the [full-scale] war, Ukrainians only had a negative opinion of Russia's leadership (13% of those surveyed had a positive opinion). Seventy-five percent had a positive attitude toward Russians, and almost 40% toward Russia as a whole.

“It was only after the invasion that Ukrainians realized that the Russian population is not being held hostage by Putin, that the majority of people support the war. Positive attitudes toward the country fell to 3% and toward Russians to 8%. But after the massive shelling and the deaths of tens of thousands of people, everything Russian became repulsive,“ the sociologist surmised.

“After the massive shelling and the deaths of tens of thousands of people, everything Russian became repulsive.”

At the same time, Paniotto explains, it is the attitude toward the Russian language that has changed more than its actual use. In 2020, when Ukrainian respondents were presented with two statements about the Russian language, 50% chose the option stating that “the Russian language is a historical treasure of Ukraine that must be developed,” and only 30% believed that it “threatens the country's independence.” However, by 2023, more than half (52%) responded that Russian should not be taught in schools at all. By 2025, this figure had risen to 58%, and only 3% now believe that Russian should be taught to the same extent as Ukrainian.

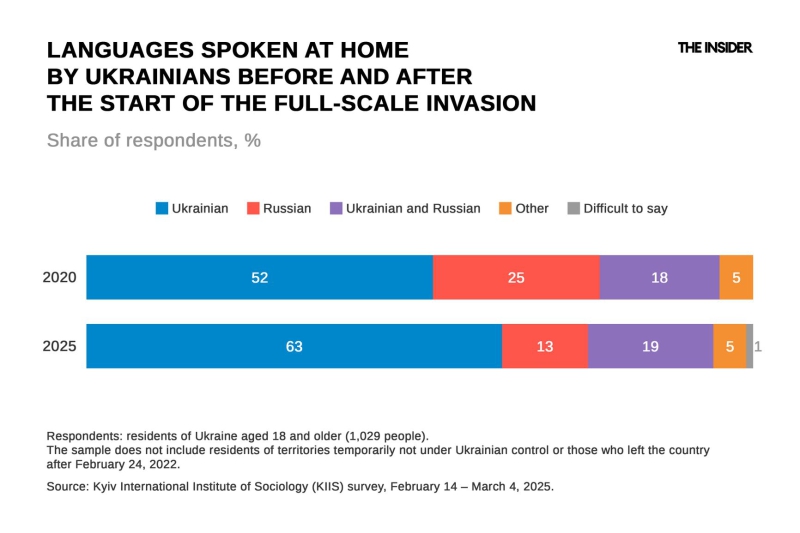

Despite the fact that many Ukrainians continued to speak Russian after the start of the full-scale war, the Ukrainian language became noticeably more prevalent. According to a survey conducted in February 2025, 63% of Ukrainians speak Ukrainian at home (up from 52% in 2020), 13% speak Russian (down from 25% in 2020), and 19% speak both Ukrainian and Russian equally.

“For many people, using the Ukrainian language is a demonstration of a strong pro-Ukrainian stance and, in some cases, a rejection of everything Russian. Some may react negatively when you speak Russian, asking: ‘Why are you still using the language of the aggressor state?’ Language has become a political and civic choice — a clear indicator of how Ukrainian you are,” says Fesenko.

Ihor from Ternopil, who spoke both Ukrainian and Russian equally well before the full-scale war began, has now switched mainly to Ukrainian:

“In my circle, people spoke 50/50, both Russian and Ukrainian, regardless of their origin. Some families from western Ukraine spoke Russian because they found themselves with people who required it, while others spoke Russian with their parents and Ukrainian with their children. Therefore, the language issue was not a key one before the full-scale war, and no attention was paid to it. When someone I knew spoke Russian, I switched to Russian, and when they spoke Ukrainian, I switched to Ukrainian, and vice versa.”

But when Russian missiles started landing in Ukraine, Ihor's attitude toward the Russian language changed:

“With the full-scale invasion, language became a marker of ‘us and them,’ and everyone around me — even Russian speakers — switched to Ukrainian. Even my ex-wife, who is Russian-speaking — unlike me, she speaks Russian without a Ukrainian accent, which is why Muscovites often took her for one of their own — switched completely to Ukrainian and still doesn't speak Russian. And when I meet new people near my home — people who moved here after the invasion — and hear them speaking Russian, I become wary.

In 2022-2023, Russian was clearly associated with the language of the enemy. Now, despite the fact that everyone understands what Russia is, the language is being taken out of the context of the war. Nevertheless, much has changed, and Kyiv itself is now a predominantly Ukrainian-speaking city. Of course, there is Russian there, but the appearance of people who demonstratively use Russian and do not switch to Ukrainian triggers many people.”

According to Ihor, he personally allows himself to use Russian in only two cases: either with very close people who are unable to switch to Ukrainian, or when communicating with foreign colleagues. In all other cases, he now speaks only Ukrainian:

“Putin's Russia puts language at the forefront because where there is Ukrainian culture, the Ukrainian language, and Ukrainian heroes, there will be no Russia, and vice versa. Wherever there are monuments to Pushkin, some Russian fascist is immediately tempted to say that this is the ‘Russian world’ and it must be defended — with weapons in hand, killing all Ukrainians. Therefore, language is the main criterion in reflecting the ideology of the ‘Russian world.’ The ‘Russian world’ is the Russian language, and the ‘Ukrainian world’ is the Ukrainian language,” he concludes.

Yuri, a soldier from Kharkiv, has also rethought his attitude toward the Russian language. After being entirely Russian-speaking, he has switched to Ukrainian, both at home and in public:

“In the nightmare of the first weeks of the war, I didn't think about language at all. I remember a guy talking to me in line at the military registration office. He was speaking Ukrainian with his friends, but he came up to me and started speaking Russian. I was surprised by that. I had always understood Ukrainian well, so it stuck with me. I started switching to Ukrainian in the army. Or rather, I just did it. It was on the front lines in the Mykolaiv Region, where most of the soldiers and officers spoke Russian, but I realized that I didn't want to anymore.”

In Yuriy's circle, which used to be Russian-speaking, there are now almost no Russian speakers left:

“Everyone around me has switched to Ukrainian. It's really widespread. All those who have switched to Ukrainian say, ‘I don't see any going back to Russian.’ Russian has become a symbol of war and violence, and it's no longer really needed as a means of communication. The overwhelming majority of information produced in Russian is propaganda promoting hatred, lies, the denigration of other peoples, racism, and other abominations. I have a friend who spent almost a year in captivity, where he was tortured and abused. Everything was in Russian, of course. When he hears Russian, he has panic attacks.”

The atmosphere in cities and on the streets has also changed. According to Yuriy, five years ago Russian was spoken almost everywhere in Kyiv, but now it is much less common: ”Often, even if everyone in a group is speaking Russian, as soon as a soldier in uniform appears, they immediately switch to Ukrainian. Not because they are afraid — what is there to be afraid of? — but because the military really triggers them. In Kramatorsk, where even government officials spoke Russian ten years ago, there is now a renaissance of Ukrainian. There are a lot of military personnel. The economy is geared towards them, and many Russian speakers simply won't be able to buy shawarma or coffee, so everything is in Ukrainian.”

Even those who have lived in traditionally Russian-speaking regions since childhood switch to Russian on the front, says Yuriy:

“At the end of the summer of 2022, I found myself with guys from Dnipro, and they all spoke Ukrainian. My friends from Mykolaiv wrote to me that they had started switching to Ukrainian and had even introduced fines for Russian words. They made everyone do push-ups. Everyone! Even the deputy commander did push-ups when the soldiers heard him speaking Russian.

Sometimes you meet people in the units who find it difficult to speak Ukrainian. I served with a guy who, when he joined in conversations, always started with the phrase: ‘Sorry for speaking like a faggot.’ Some people also call Russian ‘trophy Russian,’ but in the army, all official communication, all training, and all documentation is only in Ukrainian, so even those who initially speak only ‘trophy Russian’ get pulled in after a few months and switch completely or partially to Ukrainian.”

Yuriy himself says that, with one exception, he has not spoken Russian for at least a year and a half — once, he had to communicate with an Estonian volunteer who did not speak English but knew Russian from Soviet times.

The transition to Ukrainian was easy for Yuriy, and he had no difficulty with pronunciation or conveying meaning:

“It was like flipping a switch. And at some point, everyone around me was speaking Ukrainian, so I had constant practice. I read books in Ukrainian too. I haven't read a single book in Russian since the war started. When my daughter came back [to Ukraine], she gathered all her Russian books, including her favorites from when she was a kid, and threw them away.

I don't speak Russian, I try not to even swear, which is quite difficult in the army, and I've been thinking in Ukrainian for a long time. In fact, I don't hear Russian from my family at all — or very rarely, when someone jokes around, imitating an orc. My family would hardly ever say anything worthwhile in Russian.”

I don't speak Russian, I try not to even swear, which is quite difficult in the army, and I've been thinking in Ukrainian for a long time.

Yuriy adds that language defines one’s essence:

“Once, someone on Ukrainian Twitter asked: ‘What skill would you gladly give up without regret?’ And hundreds of people started replying: ‘The ability to speak Russian.’ That says a lot about how people feel. I’m fairly cynical about this. Russian was never some sacred cow for me, it was just a working tool.

But every tool has a limited lifespan, after which it’s no longer of any use. Right now, we’re watching how, for many people — a great many people — the lifespan of the Russian language is coming to an end. It’s becoming unnecessary, and that’s okay. Let [Russian MP] Andrey Gurulyov and [Russia’s ex-president Dmitry] Medvedev go on spewing their drunken ramblings in it. The rest of us will find other ways to understand one another.”

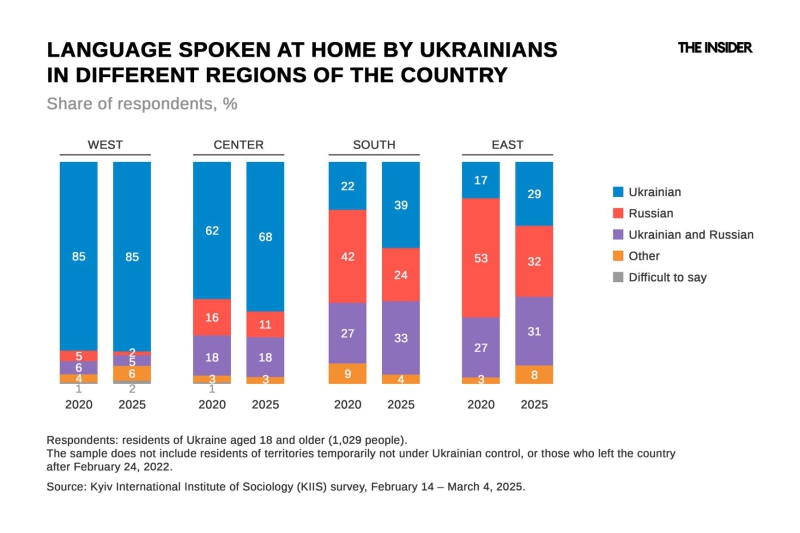

The increase in the number of people who switched to Ukrainian was most noticeable in the predominantly Russian-speaking regions in the south and east of the country, where there has been a shift of some Russian-speaking Ukrainians into the bilingual segment. For those who have spoken primarily Russian all their lives, using both languages feels like the most practical option for distancing themselves from a strong attachment to Russian.

The change in attitude toward the Russian language among residents of these regions is visible in the data, notes sociologist Paniotto, and the shift is most visible when it comes to the question of education:

“Back in 2019, more than half of the population in the south and east were in favor of Russian being taught to the same extent as Ukrainian. As of 2025, only 5% in the south and 8% in the east remain in favor of this. Among those who continue to speak Russian, 66% would like Russian to be taught in schools, but only 11% of them said that it should be studied at the same level as Ukrainian. The majority said that it should be taught at a lower level than English or German.”

At the same time, so-called “functional” bilingualism is still evident in Ukraine: many people speak Ukrainian at work and Russian at home. In the 2000s, the phenomenon was widespread in Kyiv, but it is less common now. However, people still switch from one language to another depending on their interlocutor and the situation — albeit less actively than before. As political analyst Fesenko notes:

“A telling example of this can be seen on YouTube. Some of our YouTubers broadcast in Russian to expand their audience beyond Russian-speaking Ukrainians to include the remaining Russian-speaking audience abroad. Some colleagues have made a distinction: they record videos in Russian, Ukrainian, and even English.”

Olena from Zaporizhzhia communicates in both languages. Before the full-scale war, she spoke Russian, but in 2022 she consciously switched to Ukrainian, reserving Russian only for communication at home:

“I grew up in a Russian-speaking environment and graduated from a Russian school. I speak Russian not because I love the language. Language is just language — I feel neither hatred nor love for it — nothing. What happened before, how we were taught, did not depend on us — it was state policy. And I think that switching to Ukrainian is the right thing to do. If I live in Ukraine, I should speak Ukrainian. It used to be abnormal: the country is called Ukraine, but schools and universities are all in Russian. Now I speak Ukrainian outside the home and Russian at home.”

According to Olena, she knew Ukrainian even before the war, so she had no problems with the transition. Her children went to a Ukrainian school, and all the documentation at work was in Ukrainian. Olena is not yet thinking about switching completely to Ukrainian — it is not easy when you have grown up in a Russian-speaking environment, but that is precisely why she does not feel the strong aversion to Russian that is often felt by residents of western regions. Olena explains:

“I don't reject the Russian language, but I believe that when you go to a store or a public place, you should speak Ukrainian, and at home, you can speak whatever you want. And I understand those who reject this language, especially if they grew up in Ukrainian-speaking regions, and now there is a war, and Russia is an aggressor country, so such a reaction is understandable. For me, language has also become an indicator that I am Ukrainian. It is my identity. The war has prompted many to remember this and draw a line between us and them, that we are not them — not the people who came to kill.”

Five years ago, 42% of residents in southern Ukraine communicated at home only in Russian, but by 2025, this figure had fallen to just 24%. In the east, the same measure fell from 53% to 32%. According to Fesenko, the process of national self-identification in these regions has intensified. Many have switched to Ukrainian for political reasons.

Language does indeed act as a means of identification, says soldier Mikhail from the Kyiv Region, even if he stresses that Russian is still acceptable to use in many instances:

“In 35-40% of cases, we continue to use Russian at home, with family and friends, but in public spaces and government agencies, we only use Ukrainian, although if you start speaking Ukrainian and then continue in Russian, it's no big deal. The only cases that are stressful are when someone insists on speaking only Russian — this is perceived as something hostile: maybe this Russian is a murderer, a looter, a rapist.”

As Mikhail adds, Ukrainians who are more fluent in Russian will often speak a blend of the two languages, using Russian words and phrases to express complex ideas while sprinkling in basic Ukrainian words to signal that they are making an effort to make the change. “In my opinion, that’s normal,” he says.

Two languages are also present in the life of Tetiana from Kyiv. She communicates in both Russian and Ukrainian at home and at work:

“The situation in my family is not quite standard. My husband is neither Ukrainian nor Russian. He only learned Russian and, accordingly, cannot speak Ukrainian properly, although he tries. Therefore, we communicate in Russian at home, but when my friends come over, we speak Ukrainian. My child also speaks Ukrainian, listens to Ukrainian music, and studies in Ukrainian.”

Like many Ukrainians, Tetiana has known both languages since childhood:

“My grandparents are from a small town in the Poltava Region, and I spoke Ukrainian with them. My other grandmother, the daughter of exiles, studied in Siberia before World War II and only knew Russian, so I spoke Russian with her and my parents, but as soon as I visited my other grandmother in the Poltava region, I immediately switched to Ukrainian. That's why I still consider Ukrainian my native language, even though I studied in Russian at school. It was the policy of Russification that led to many people over 40 having problems switching to Ukrainian before the full-scale invasion.”

However, there is a clear trend toward a complete transition to Ukrainian, which is directly linked to the ongoing Russian attacks on urban infrastructure. Tetiana notes:

“There are those who spoke to me in Russian just a couple of months ago, but now they speak Ukrainian every time we talk. A friend of mine from Donetsk, who usually spoke Russian, started writing to me in Ukrainian on social media. At the beginning of the war, switching to Ukrainian was a means of identification. There were many [sabotage groups] around then, and if you came across someone, you immediately addressed them in Ukrainian, assuming that the Russian army couldn't recruit enough paratroopers who could speak Ukrainian without an accent. Now, I think this shift is related more to the [missile and drone] strikes and the loss of loved ones.”

She clarifies that while the Russian language has not completely disappeared from Ukrainian life, it appears to be on its way to oblivion:

“We are bilingual and can speak both languages, but more and more people don't want to speak Russian. It was the same in the Baltic states, where people learned Russian in school and then stopped speaking it. Recently, there has been a real feeling that language is how you identify yourself. We are like a small guerrilla unit: to understand whether someone is one of us or an enemy, we use language, and this is very powerful.”

Not everyone in Ukraine believes this trend is for the best — and not because they are desirous to join the “Russian world.” Sociologist Volodymyr Paniotto would like to see both Russian and Ukrainian continue to play prominent roles in Ukrainian culture:

“For me, the war has not changed anything in terms of language. I agreed with Timothy Snyder's concept that we must not give Russia our language as well, but must have our own language rules and institutions for its development, like the U.S. and the UK. We must form a Ukrainian political nation by working harder to foster Ukrainian patriotism among Russian speakers, but I fear that this is no longer possible.”

Panitto's point of view is not unique. Russian speakers in Ukraine may be in the minority, but the overwhelming majority of them continue to see Russia as the aggressor in the war and hope to see the perpetrators of war crimes brought to justice. Lyudmila, from Kherson, argues that the language a person speaks is the last thing that should be of concern when the country is at war:

“To be honest, we spoke Russian before and we continue to speak Russian. We left western Ukraine because there was harassment for every wrong word spoken in Ukrainian, and it was very difficult to live there. We returned to the south, and here everyone speaks as they please: some have switched to Ukrainian, some have not. But I started using social media in Ukrainian because I was constantly asked, ‘Why not the state language?’ I think that in the south, people don't consider Russian to be the language of the aggressor, since we've spoken it since childhood. For example, just like in western Ukraine, the Polish dialect is common. All these disagreements about language between the two parts of Ukraine are very stressful.”

According to political scientist Fesenko, the future of the Russian language in Ukraine may repeat the experience of the German language after the defeat of Hitler's Germany eight decades ago:

“During World War II, German was perceived as the language of the enemy. And this is a telling phenomenon: after the war ended, the situation normalized — not only in our country, but also in other European countries — and people came to understand that German is not just the language of Hitler, but also the language of Goethe and Heine, and of all German culture, so it cannot be identified solely with Hitler and cannot be taboo. I think that in the future, the same situation will arise with the Russian language.“

Documentary filmmaker Ihor Poddubny continues to speak Russian:

“I can't say that I have any aversion to the Russian language. Some of my friends have switched to Ukrainian, and I understand them. I speak to them in the language I am used to speaking. Some of them are also switching to it, some are not. We don't get hung up on it. I understand that Russia is bombing us, but to be honest, I don't think those who are firing at us have read Pushkin.”

I understand that Russia is bombing us, but I don't think those firing at us have read Pushkin.

Poddubny encountered disputes about language when he set out to make a sequel to his film Ordinary Ruscism:

“After the film [about Russia] was released, there were comments asking, ‘But isn’t that what things are like in Ukraine, too?’ So we decided to make a sequel that included Ukraine. We asked displaced persons questions about how they were living and what they liked or disliked, but it seemed completely inappropriate to publish the results of these conversations during the war. So the script for this film, which contained all the fears of the displaced persons, was sent in the form of a letter to a specific Ukrainian government minister responsible for this issue.”

According to Poddubny, young people are actively switching to Ukrainian, but in his own circle, the percentage is quite small:

“There is a profound shift to Ukrainian among young people. But in my generation, I have not met a single person who has switched to Ukrainian or used epithets to cover their entire previous history of communication in one language or another — nor who would like to change their parents' epitaphs in the cemetery to Ukrainian. Whether we like it or not, according to a study we conducted with [communications operator] Kyivstar, 42% of people living in Ukraine do not consider Ukrainian their mother tongue. And these are people within the current borders, not the former ones.”

Russian can still be heard on the streets, but attitudes towards it have changed more in public spaces than in everyday life, says Poddubny. He notes that attitudes toward the Russian language have changed more on social media, with many posts appearing in public groups calling on people to “speak Ukrainian because the enemy speaks Russian.” YetRussian can still be heard on the streets of Kharkiv. At the same time, Poddubny understands how foreign demagogues can exploit language issues in order to justify their illegitimate actions:

“I would like to remind you that in 1938, when Hitler arrived in Vienna, he was also very dissatisfied: 'You speak German, but you are some kind of Austria. If you speak the same language as me, let's call you something else.’ And he changed the name of the country. On this point, I really want to say to Trump, who says, ’They speak Russian there, let it be Russia,’ that he is the Hitler of the 21st century.”

He adds that it is important to recall that Ukraine has always been a multinational state:

“Aside from the endless fear that the war must end, people are afraid of losing the culture they would call their own. And that is why people are coming from half-bombed Kherson to half-bombed Kharkiv — they want to stay in their own environment. Therefore, the language issue is a problem that we need to resolve at the round table in a civilized manner, not in some barbaric way. And we must remember that in 2014, every TV channel had a caption in the corner that read: “Україна — міжнародна великомовна держава“[“Ukraine is a multilingual state”], which is why the Crimean Tatar people, the Ukrainian people, the Sloboda people, and others are all indigenous peoples.

No one has the moral right to tell another person what language they should speak.”