Volunteers Distribute Food to Palestinians in the Gaza Strip

Under pressure from Western countries, Israel has announced daily humanitarian pauses in hostilities in Gaza, promised an increase of humanitarian aid allowed into Gaza from UN agencies, and launched food airdrops. The humanitarian crisis in the region is also playing out in the field of information war: while some Western politicians and media accuse Israeli authorities of weaponizing hunger, Israel says that there is no hunger in Gaza and that the accusation is part of a Hamas propaganda campaign. The Insider has gathered everything currently known about the real state of food aid delivery in Gaza.

For several months, journalists and international humanitarian organizations alike have been reporting on the food shortages in Gaza. As early as the beginning of July, Gaza residents told The Insider’s correspondent that they had no access to food. However, the issue only truly captured widespread public attention in mid-July, when international agencies released photographs of children in Gaza visibly emaciated due to malnutrition. One of the images showed a child exhibiting signs not only of undernourishment, but also of illness, sparking fierce debate in certain corners of social media.

One of the most widely circulated images — first published by The Daily Express and later featured on the front pages of major outlets such as The New York Times and The Daily Mail — shows one-and-a-half-year-old Mohammad Zakaria Ayoub al-Matouq. The boy appears frighteningly emaciated.

Shortly after the photo’s release, British activist and independent journalist David Collier published information on his website claiming that Mohammad is, in fact, suffering from a genetic disorder. “This is not the face of hunger. This is the face of an unwell child whose suffering was weaponized — first by Hamas, then by the global media.” Collier noted in his article that he had seen a medical report dated May 20, 2025, diagnosing Mohammad with cerebral palsy and hypoxemia. Collier did not include a copy of the document in his article, but he provided it upon request to the German broadcaster ZDF. According to the channel’s website, the journalist failed to disclose the full contents of the medical report: in addition to the aforementioned diagnoses, it states that the patient is “suffering from severe malnutrition” and “requires nutritional supplements in any available form.” Following Collier’s report, The New York Times published a clarification on Twitter (X):

“Children in Gaza are malnourished and starving, as New York Times reporters and others have documented. We recently ran a story about Gaza’s most vulnerable civilians, including Mohammed Zakaria al-Mutawaq, who is about 18 months old and suffers from severe malnutrition. We have since learned new information, including from the hospital that treated him and his medical records, and have updated our story to add context about his pre-existing health problems. This additional detail gives readers a greater understanding of his situation. Our reporters and photographers continue to report from Gaza, bravely, sensitively, and at personal risk, so that readers can see firsthand the consequences of the war.”

Another photograph sparked a similar reaction. Italian newspaper Il Fatto Quotidiano, in illustrating the hunger crisis in Gaza, featured on its front page a striking image of an extremely emaciated boy — five-year-old Osama al-Rakab. In response, the office of the Israeli government’s Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT) issued a statement refuting the claim, stating that the child was gravely ill and had, with COGAT’s assistance, left Gaza on June 12 to receive medical treatment in Italy. COGAT accused the newspaper of antisemitism. In reply, the newspaper pointed out that, judging by a photo of Osama in the hospital — released by COGAT — the child, upon receiving proper nutrition and medical care, looked entirely different and bore little resemblance to the skeletal figure seen in the widely circulated images. This, the paper argued, strongly suggests that the issue was not solely a matter of a “genetic disorder.”

It is important to note that, beyond these particular photographs, agencies have published dozens of other images of severely emaciated children in Gaza — none of whom have been subjects of any controversies regarding «genetic disorders.»

Shortly after these debates were seemingly settled, an article in The Spectator received widespread attention in Israel. It claimed that the leadership of the BBC had circulated a memo to its staff titled “Covering the Food Crisis in Gaza.” The article summarizes the contents of the alleged document, accusing the British broadcaster of instructing its journalists to follow a strict editorial line when reporting on the situation in Gaza. According to the piece, for example, staff were allegedly told to write that the distribution of food by the US-Israeli Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF) is ineffective. However, no copy of the memo was provided. At the time of this article’s publication, the BBC had not responded to The Insider’s request for comment. Sources within the BBC’s Russian Service told The Insider they had not received a memo fitting The Spectator’s description — nor had they received anything similar.

In early March, after two months of nearly unrestricted food delivery and a ceasefire, Israel suspended the access of humanitarian aid to Gaza, citing concerns that the deliveries were entirely under Hamas control. The IDF officially stated that Hamas was seizing around 20% of all humanitarian shipments — a claim denied by humanitarian organizations operating in the region. USAID, for instance, conducted an internal investigation which found no evidence supporting Israel’s assertion that Hamas was systematically looting aid convoys. In an effort to reduce Hamas’s leverage over the civilian population, a joint American-Israeli initiative was launched to replace the UN humanitarian agencies operating in Gaza. This initiative — the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF) — began operations on May 27. On July 2, The Insider provided a detailed report on the creation and structure of the GHF, and since then, the procedures at distribution points have remained unchanged. There are still only four functioning distribution centers, all of which are located in the southern and central parts of Gaza. Israeli authorities and GHF leadership have repeatedly stated their intention to open an additional distribution point in the northern part of the Gaza Strip — but this has yet to happen.On August 7, U.S. Ambassador to Israel Mike Huckabee announced that new GHF distribution sites would be opened in Gaza and that they would operate around the clock. However, Huckabee did not specify when this would actually take place.

At present, there are far too few food distribution points, and the number of people in need is overwhelming. Distributions take place in conditions of complete chaos and crowd surges, and incidents involving gunfire and fatalities occur regularly. According to the Red Cross and Médecins sans frontières, their hospitals continue to receive patients wounded near GHF distribution sites on a daily basis. As of July 31, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) reported that the number of Palestinians killed while trying to obtain food at GHF sites had exceeded 1,300. Initially, Israeli authorities blamed the shootings on Hamas. However, following reports published in the newspaper Haaretz, the IDF acknowledged that it does at times open fire in order to “disperse the crowd.” In mid-July, the Israeli army also admitted that, in certain instances, fire had been opened from naval vessels. Meanwhile, wounded people treated in hospitals after such incidents report that security personnel at the distribution sites also open fire on them.

The foundation reports that, as of August 4, a total of 106 million portions of humanitarian aid have been distributed to Gaza’s population. However, since the distribution points operate only in the southern and central parts of Gaza, many residents must walk several kilometers to reach them. Moreover, the amount of food available is limited, the distribution points do not always operate, and they are often shut down just minutes after opening. This has been corroborated by data from the London-based research group Forensic Architecture, which cross-referenced information from the GHF’s Facebook page (which Gaza residents use to learn about the operation of distribution points) with data from other open sources.

According to Forensic Architecture’s analysis, between May 29 and July 4, the average daily operating time of distribution points was just 23 minutes. In 60% of cases, notification of a point opening was published less than an hour in advance. In some instances, sites opened and closed earlier than announced.

It’s worth recalling that when the distribution points were first announced, officials promised that weekly food parcels would be handed out according to lists — one package per family. In practice, however, no such lists exist, and there is no organized distribution system. Residents rush the aid trucks and grab whatever they can carry. On August 5, for the first time in many months, a foreign journalist was allowed into Gaza — Bill Hemmer of Fox News. In his report, Hemmer includes an interview with a foundation employee who explains that, in most cases, within 15 minutes there’s nothing left of the humanitarian aid.

As a result, humanitarian aid reaches only a small portion of Gaza’s population. This, along with the fact that GHF distribution points are located in areas controlled by the IDF and accessible only via roads that pass through active combat zones, led the UN to refuse to cooperate with the foundation. From mid-May until July 26, Israel allowed only limited humanitarian shipments into Gaza — and only for UN-agencies.

By July, the humanitarian situation in Gaza had sharply deteriorated. According to Gaza’s Hamas-controlled Health Ministry, 175 people have died of hunger since the start of the war — including 93 children. But it is not only unreliable organizations providing such estimates. On July 27, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that in the month of July alone, 63 people in Gaza died from severe malnutrition — among them 24 children under the age of five.

According to the WHO, 63 people in Gaza died from severe malnutrition in July alone — including 24 children under the age of five.

In response to The Insider’s inquiry, the Red Cross stated their field hospital in Rafah continues to receive patients showing signs of malnutrition. According to the latest report from the IPC Hungermonitor — an initiative that collaborates with the UN to track global food security — Gaza City is currently experiencing a “worst-case hunger scenario.” Two of the three hunger threshold indicators have been met: a sharp drop in food consumption and the appearance of acute malnutrition. According to the report, the most severe situation is in Gaza City, where there are no GHF distribution points and where, until July 26, Israel had allowed humanitarian aid deliveries only on rare occasions. The report states that 16.5% of children under the age of five in Gaza City are suffering from malnutrition.

IPC-Hungermonitor reports that 16.5% of children under the age of five in Gaza City are suffering from malnutrition

Different organizations assess the severity of hunger using a range of methods. According to an analysis by the Nutrition Cluster in the State of Palestine (SoP) — one of the key sources used by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs — as of early July, 9% of the 56,000 children of all ages examined in the Gaza Strip were found to be malnourished. In June, that figure had stood at 6%.

Doctors from Médecins sans frontières (MSF) regularly conduct screenings at their clinics in Gaza, focusing on children under five along with pregnant and breastfeeding women — the groups most vulnerable to malnutrition. MSF told The Insider that their latest screenings found one or more forms of malnutrition in 25% of their patients.

MSF operates several medical facilities in Gaza, both in the north and in the south. The Insider spoke with Natasha Davis, a senior nurse from the UK working at MSF’s southern facilities. At the time of the interview, she was stationed at the field hospital in Deir al-Balah. According to Davis, the supply of food to hospitals has somewhat improved recently. The hospitals are supported by the U.S.-based organization World Central Kitchen (WCK). Prior to the suspension of aid deliveries to Gaza in March, patients and medical staff alike received one hot meal every day. But for several months after the halt, meals were provided only for patients. For the hospital’s staff — most of whom are local residents — this had been their only reliable source of proper nutrition, Davis explained. Recently, WCK resumed delivering hot meals for both patients and staff.

Humanitarian organizations and local residents told The Insider that, despite Israel’s July 27 decision to increase the amount of humanitarian aid allowed into Gaza, little has changed in practice. Ilham, a woman The Insider spoke with in early July, says her family receives no aid at all. Prices at local markets remain prohibitively high, and so they survive on nothing but rice and beans. Another interviewee, Mohammad, who lives in the northern part of Gaza, recounted how he tried to collect food when the Zikim crossing was briefly opened. However, gunfire broke out near the checkpoint, and he has not returned since.

Indeed, following the opening of the Zikim crossing in northern Gaza, there have been multiple reports of local residents being killed or injured by gunfire in the area.

Olga Cherevko, a staff member of OCHA in the Gaza Strip, confirms that food does not reach many residents and that humanitarian convoys are often emptied almost immediately after leaving the checkpoints. Starving civilians and armed gangs wait for the trucks along the roads — with the latter seizing goods in order to resell them at local markets. According to UN data, nine out of ten humanitarian aid trucks that have entered Gaza in recent months have been looted before reaching their intended destination.

Food prices serve as a reliable indicator of the amount of aid reaching Gaza, and real-time tracking is available on a webpage maintained by the Cash Working Group. Compared to March, prices for most staple goods have risen approximately tenfold.

According to OCHA, 70% of agricultural land in the Gaza Strip has been destroyed during the war. The remaining 30% is located in the north or near Khan Yunis in the south. Both of these areas lie within active combat zones, making harvesting extremely dangerous.

The office of the Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT), which began responding to media inquiries again only after July 27, told The Insider that previously banned fuel is now being allowed into Gaza, along with a significantly expanded list of food and medical supplies. The Zikim checkpoint in northern Gaza has opened, allowing humanitarian organizations to transport aid directly from the Israeli border to Gaza City. Additionally, three other checkpoints are operational: Kerem Shalom in the south and two crossing points in the central part of Gaza. Just like in late 2024, COGAT representatives emphasize that shipments often wait at the border for extended periods until humanitarian convoys collect them. They made clear that COGAT itself does not obstruct these convoys.

On July 30, OCHA staff member Olga Cherevko accompanied a convoy assigned to collect a fuel shipment from the Kerem Shalom crossing. According to her, that single round trip from Deir al-Balah — where OCHA’s headquarters is located — to Kerem Shalom and back took sixteen and a half hours:

«We left at six in the morning and reached the first stop, where we needed to obtain an additional permit from COGAT. The wait took about two hours. We arrived at Kerem Shalom at 9:30 a.m. Loading was completed at around 2:00 p.m., but the convoy didn’t receive permission to return until around 8:30 p.m. We then waited another hour at the next checkpoint, and afterward unloaded the fuel at the depot. I finally got home at 10:30 p.m.»

It took 16.5 hours to collect a fuel shipment

Olga explains that this is what a typical run to the checkpoint and back looks like. Sometimes it’s faster — other times, even longer.

As for the shipments themselves, Cherevko notes that the amount of fuel entering Gaza remains far below what is needed. Gaza requires hundreds of thousands of liters per day, while at best, only several tens of thousands are being brought in.

Recently, Haaretz published a report in which drivers delivering humanitarian aid to GHF distribution sites said that their convoys are escorted by the IDF from the border to the drop-off points. COGAT has denied this claim.

As for the airdrops of food aid — which were also authorized on July 26 — humanitarian organizations consider the initiative to be largely ineffective. First, even accounting for contributions from several countries (the initial airdrop was carried out by the Israeli Air Force, followed by drops from Jordan, Egypt, the UAE, Germany, and others), the total amount of aid delivered by air remains minimal compared to what can be transported by land. According to COGAT, these efforts amount to, at most, a few dozen tons of food per day. Moreover, the drops are scattered and uncoordinated. As OCHA explains, the supplies often fail to reach the people who need them most.

In the end, the supplies are seized by those who are stronger or who happen to be closest to the landing site. It’s worth noting that this is not a new practice: Western countries, with Israel’s permission, had already resorted to airdrops in the early months of the war. However, after several incidents in which local residents were killed, the practice was suspended.

Media outlets, citing unnamed sources, report that Israel is considering reopening Gaza to commercial food imports. Goods intended for private-sector trade were allowed into Gaza until approximately October 2024. In December 2024, COGAT officials told The Insider that private vendors in Gaza were inflating prices, diverting supplies to Hamas, and ultimately preventing food from reaching those who needed it most. Humanitarian organizations, however, pointed out that the removal of private trade only gave rise to a black market, where prices soared even higher and access to food became even more limited.

In Olga Cherevko’s view, the only way out of the dire humanitarian crisis — and the only way to prevent a further rise in hunger-related deaths — is to significantly increase the amount of humanitarian aid that Israel allows to enter Gaza.

The only way to prevent a rise in hunger-related deaths is to increase the amount of humanitarian aid allowed into the Gaza Strip, says Olga Cherevko of OCHA.

In addition to the food shortage, Cherevko notes a severe lack of tents and other essential equipment for refugees. According to her, these supplies have not been permitted entry into Gaza for over 150 days. As a result, more and more local residents are being forced to sleep out in the open.

The sanitary situation in Gaza has deteriorated so drastically that the Israeli government has authorized the resumption of water deliveries from Egypt. According to Natasha Davis, the vast majority of patients at the MSF clinic in Khan Yunis are seeking treatment for gastrointestinal, respiratory, and skin diseases. The clinic’s six doctors see between 700 and 800 patients per day, Davis says. The MSF field hospital, designed to fit 90 beds, typically holds 110 to 115 patients. It is a surgical facility, operating three theaters during the day and one at night, performing between 30 and 40 operations a day. Most of the cases involve patients with gunshot wounds, shrapnel injuries, blast trauma, and amputations.

Six doctors see between 700 and 800 patients per day at the Médecins sans frontièresclinic

«A quiet day for us is when there’s only one mass-casualty incident in the southern part of Gaza,» says Davis.

The nurse explains that many children arrive at the clinic with severe burns — and not always from explosions. Families live in overcrowded conditions and cook over open flames, which often leads to injuries among children.

According to Davis, virtually every patient at the hospital is suffering from some degree of malnutrition. Because their bodies are weakened, wounds heal more slowly and are more prone to infection, and thehospital is already facing a shortage of basic antibiotics. In recent months, surgeries have also frequently been delayed due to equipment failures.

Davis adds that recently, two trucks arrived at the hospital carrying supplies of medicine, gauze, and bandages. “We perform 70 to 80 wound dressings and 30 to 40 surgeries a day. When we run out of bandages and gauze, it’s the end of the world,” she says.

«I’ve worked in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Yemen. But I’ve never worked under conditions like these.» I can't compare human suffering in one place or another, and I understand very well what war means — but it’s impossible not to feel despair when people’s lives and deaths here depend entirely on whether Israel chooses to open or close the border.»

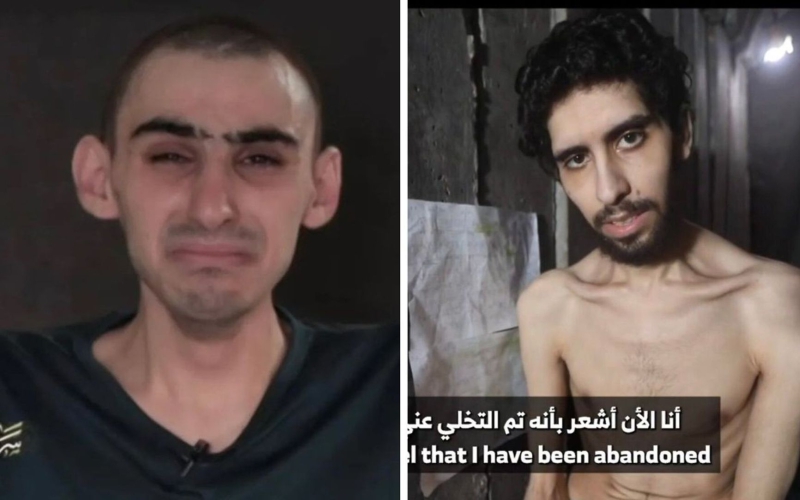

At the time of this publication, 50 Israeli hostages remain in captivity in Gaza — under Hamas control. Of those, 20 are believed to still be alive. Just days ago, Hamas released a video featuring two of them — Rom Breslavski and Evyatar David.

Both men appear extremely emaciated, having lost nearly all muscle mass. In the video, they state that they receive almost no food or water. Rom Breslavski is filmed lying down, saying he is too weak to stand. Evyatar David is shown in a tunnel, digging what he says is his own grave.

After the release of these videos, tens of thousands of Israelis took to the streets, demanding an end to the war and the return of the hostages. Yet Israel and Hamas have still not reached an agreement on the terms for the hostages’ release, let alone for a ceasefire. Hamas refuses to lay down its arms, and in Jerusalem, officials maintain that allowing the militant group to remain in power in Gaza would amount to a defeat for Israel and could lead to future attacks on the scale of the October 7, 2023 invasion.

On August 7, the Israeli war cabinet approved a decision to bring the entire Gaza Strip under full Israeli control — despite opposition from the IDF’s Chief of General Staff. According to a statement released by the office of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, the operation will begin with the takeover of Gaza City. The city’s residents — estimated at around 800,000 — will be advised to evacuate southward toward the central refugee camp areas. Israel has pledged to provide humanitarian aid to those zones.

In the second phase of the plan, Israel intends to seize the refugee camps in the central part of the Gaza Strip with the goal of relocating the entire population to the southern al-Mawasi area — where hundreds of thousands are already living in tents. According to a statement from the Prime Minister’s Office, this strategy aims to achieve the disarmament of Hamas, the return of both living and deceased hostages, and a change in Gaza’s leadership. The statement further declares that, following the execution of Israel’s plans, Gaza will be governed by an alternative administration — one unaffiliated with either Hamas or the Palestinian Authority.

IDF Chief of General Staff Eyal Zamir expressed strong opposition to the plan, warning that its implementation could result in the deaths of the remaining hostages and lead to heavy casualties among Israeli soldiers.