For the first time since World War II, parts of Russia’s Kursk Oblast have fallen under the control of foreign armed forces. Locals feel abandoned by their government, and even the most loyal are losing faith in the regime, notes The Insider‘s correspondent, who has visited the city of Kursk and traveled around in its vicinity. Refugees from the border zone are vocal in their condemnation of local officials, who evacuated in due time, leaving the population behind. They also have harsh words for the federal government back in Moscow, which unleashed a war that has now stripped thousands of ordinary Russians of their homes and livelihoods. The only state compensation they can hope for is a meager allowance of about $110. Some refugees are denied even that much. Even families with children have to stand in line for hours to get humanitarian aid. In this context, many refugees are curious to learn more about evacuating their relatives from Ukrainian-controlled territory to Ukraine itself via announced humanitarian corridors.

The first sound we hear in Kursk is the roar of a jet plane, invisible because of the clouds. “It's a military transport plane carrying the wounded. There are plenty,” Kursk resident Petr explains. “When I stopped for gas near the airport, I saw three buses full of heavily wounded soldiers drive by. They’ll be flown to other cities.”

We are headed to a humanitarian service point — one of the 84 recently established in Kursk. A white van without any logos dashes by, its rooftop covered with a camouflage net — an ambulance en route to the border areas. The van looks more like a military vehicle than a medical one. According to my interviewee, Ukrainian forces “target ambulances specifically,” so Russians mask their cars and place mobile electronic warfare systems on the roof. I venture to assume that Ukrainians could be targeting these vehicles precisely because of their military aspect, but Petr rejects this reasoning:

“It's just that they feel an animal sort of hatred towards us. They shoot at everything. Hardly a surprise — they’re in a lot of pain. Say what you want, but we invaded them first.”

Unlike Belgorod, a border city that looked almost like a ghost town during heavy shelling this past spring, in Kursk, stores, shopping malls, and beauty salons remain open. The only exception is Sudzha Sausage, which launched a sale on the last batch of delicacies now that Sudzha, the town where the plant is located, has fallen under Ukrainian control. Since the federal government declared an emergency in the region, armed soldiers in armored vests have been guarding government buildings, transportation nodes, and even the pedestrian bridge across the train tracks. “Today they set up checkpoints at the entrance to Kursk, on the road to Kurchatov,” Petr says.

The Kursk railway station is ten kilometers away from the civilian airport and the military airfield. “If you drive on, you’ll see an air force base and five or so military bases, so it could be expected that Zheleznodorozhny District has it the hardest. Everything is aimed in that direction. And then they’re shooting back,” the driver sighs. This is also where missiles are shot down.

On the night of Aug. 11, one such missile hit a nine-story apartment block on Soyuznaya Street, injuring 15 people. Some of the tenants were relocated, but the authorities promised to restore the building. Across the street from the damaged house is a military enlistment office, with its wall decorated with orange-and-black St. George's ribbon and emblazoned with inspirational slogans like “Victory will be ours!” and “Join your people!”

“My son had seven friends. They grew up at the same military base together,” Petr shares. “Everyone except my son ended up in the same military unit. They faced the Ukrainians at the border when the breakthrough happened. All seven are dead. They were conscripts, 18 years old. They’d only just gotten their uniforms and assault rifles. Killed right on the spot. It was a shock for everyone. Well, maybe not everyone. I’ve heard Penitentiary Service officers say that the Sudzha city administration left three days before the offensive with all their belongings. I think they got a clear message it was time to jump ship.”

“My son had seven friends. All except my son ended up in the same military unit. They faced the Ukrainians at the border when the breakthrough happened. All seven are dead. They were conscripts, 18 years old”

Nevertheless, Petr believes that Russia needs to regain control over the entire territory of the region before dealing with the corrupt officials. “First, we must take care of our common foe because they are already on our land, and then we can turn to internal enemies,” he says. “But it’s the internal enemies who are keeping us from winning!” an elderly man lining up for humanitarian aid interjects. We have arrived at the humanitarian service point on Belinskogo Street — the largest one in Kursk.

“Come on, folks, two steps back! Two, not one! Are you hearing me? Step back, or no more humanitarian aid today! We can’t unload the truck because of you!” A volunteer at the humanitarian aid point in Belinskogo Street shouts at the crowd that is about to burst through the plastic red-and-white caution tape tied between the trees. The aid point provides mattresses, linens, and other essentials for refugees from villages even closer to the border. The demand is so great that volunteers have no time to unload the truck — they are short-staffed. The aid point closes for a ten-minute break, infuriating the crowd.

“We’ve been standing here with our kids in the heat since six in the morning to get a mattress, some underwear, and ‘pampers’ for the baby,” says Sergei, who came from the border village of Kuybyshev in Rylsk District, 100 kilometers southwest of Kursk. “If you need baby items, you have to present the baby, or you’ll get nothing. I’d say we should be given a bag with all the essentials and food for the children right away, if everything we've been told about our country's greatness is true. Instead, we only get humiliation.”

A girl in line shares similar sentiments: “On our first day, we went to the public services outlet to file an application for my mother. We spent the entire day there, almost ten hours. And then it closed down. On the second day, we stood in line from 11 a.m. till 8 p.m. That’s almost 24 hours combined. My husband and I are okay with that, but we have a grandmother who uses crutches. And they told us she had to come in person! How am I supposed to bring her? She can barely make her way to the toilet!”

Two elderly men are smoking outside. When I ask them to share their evacuation experience, they get mad — the memories are too vivid:

“What’s the point in talking? How did we get out? Ask Putin, that scoundrel! There was no evacuation at all! You won’t write it anyway! I wish everyone in the Kremlin would drop dead,” one of the men says forcefully, nearly shouting. The other adds that he managed to get out with his wife and child only on Aug. 14, but refuses to specify the location: “I’ll say no more, or they’ll kill us all because of it before long. We drove at night. They [Ukrainian troops] were in position, shooting from an RPG from time to time. They let us pass. But they could have shot us dead, like they shot others before us. Thanks for the f*cking evac.”

The new arrivals are easy to distinguish: women are wearing bathrobes and slippers, and their husbands are dressed in crumpled t-shirts or button-downs. The only topic of conversation is how they got out and what to do next. Many have nowhere else to go. Dmitry lives in Kursk, but his relatives come from villages near the border. At present, all 13 of them are living in his two-bedroom apartment:

“We picked up our relatives and were driving along the road from Sudzha. I’m flooring it, all drenched in sweat, not even looking at the speedometer. There are shots and my only thoughts are, ‘please, let them miss, please, let the car pull through.’ I see a lot of cars with bullet holes in the city. My parents-in-law, my brother with his wife, my parents, my aunt and uncle, my own three kids — everyone's at our place now.”

Galina from Sudzha is making do in even harsher conditions — 11 refugees squeezed into a one-room apartment. She plans to leave Kursk for the neighboring Lipetsk Oblast and find a job as a cashier, but in doing so, she will likely lose the $110 allowance promised by acting governor Alexey Smirnov. Those who leave the region are no longer entitled to monetary assistance. Like many others, the family of Sergei from Rylsk District has yet to receive any payments, although he applied a full week ago.

“Nothing but the clothes on our backs. Staying at a private apartment. No one compensated us anything! We can't even get the goddamned 10k [rubles, approximately $110]. Our application hasn't even been processed yet!” complains a pensioner from the village of Zvanoye, Glushkovo District, where evacuation was announced on Aug. 14. “But if you watch the news, everything's been under control for three years now!” her husband interjects sarcastically.

Many are outraged that the authorities left them behind, even though Kursk Oblast residents actively helped the Russian army before the full-scale invasion. “Even back then the government did nothing. They sent soldiers to war without boots or clothes!” Anna from Zvanoye says. “See? That’s how [former Defense Minister] Shoigu sent them to war on February 23 [2022]! We gathered clothes for them and fed them. Our kindergartens and schools offered them meals. No one even gave us the supplies — we bought everything ourselves! What they showed on television — field kitchens baking bread and the like — it's all lies!”

Stories of refugees from the border areas of Kursk Oblast have a lot in common: there was no organized movement, and people had to travel under fire. The state did nothing and did not even announce evacuation in due time, abandoning the population in villages under Ukrainian control. Those who have stayed cannot leave safely and thus remain stuck in a war zone. As of Aug. 21, the region has 84 temporary shelters hosting approximately 7,000 people, according to the local authorities. Meanwhile, as many as 120,000 people have left their homes.

There was no organized movement, and people had to travel under fire. The state did nothing, and some of the population ended up stuck in villages under Ukrainian control

When Alexander, a 60-year-old resident of Korenevo, realized that Ukrainian forces were approaching his village, he joined other men and went to the military enlistment office, asking for weapons to defend his home. But there was no one to talk to. “I didn't even consider leaving. I wanted to stay for as long as I could. But our military enlistment officer had made a run for it. The office was closed. We didn’t believe it at first. But we also realized things were bad,” Alexander recalls.

“We came asking for weapons, but the military enlistment officer had run away!”

All locals interviewed by The Insider are unanimous: municipal authorities had known about the Ukrainian offensive and had evacuated in advance, following the “elite” Chechen unit Akhmat, which was supposed to be defending the border. Maria, a pensioner from Korenevo, spent three hours waiting outside the community center with a few of her fellow villagers. The head of the district had promised to send evacuation buses.

“People arrived at the community center at 5 a.m. We waited for three hours, but no one came for us,” Maria says.

Volunteer Anatoly, who helped residents evacuate, says that Sudzha District officials also left people behind.

“TikTok warriors from Akhmat had left two weeks prior, and Sudzha District administration and police were gone three days in advance. They made a quiet exit. No one told the people anything — otherwise the administration would’ve had to stay until the last minute!”

According to Anatoly, many refused to leave in early August, fearing that soldiers— whether Ukrainian or Russian — would loot their homes.

Many refused to leave in early August, fearing that soldiers — Ukrainian or Russian — would loot their homes

“We were stuck on the road at half past six on Aug. 6. We couldn’t leave because we had no car. Our mayor, Slashchev, drove past us at full speed, heading for Kursk,” Sudzha resident Irina recalls. A week later, on Aug. 15, the official denied that the town had come under the control of the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU), calling a report by the Ukrainian channel TSN a “hoax.” “Sudzha is ours, has always been, and will always be,” Slashchev said. By then, the AFU had controlled most of the town for a full week.

Natalia evacuated from Sudzha in a rush on Aug. 6 with her children, forgetting to pack their papers. She managed to get out during a pause in hostilities.

“The worst thing is that everyone knew [the Ukrainians] were pulling NATO equipment to the border. A full month ago! It was common knowledge, but our administration told us nothing. Without the internet, we’d be dead by now.”

“Everyone knew the Ukrainians were pulling NATO equipment to the border. A full month ago! But our administration told us nothing. Without the internet, we’d be dead by now”

Ever since the full-scale war began, the Kremlin has been calling on Russians to trust “only official sources,” dismissing any alternative reports as fake. And even though many Kursk Oblast residents knew by word of mouth that Ukraine had been pulling forces to the border, they stayed home, waiting for official instructions from the authorities — but none came. “There are mostly old folks there. They’re used to everything being proper and official, but here’s what they got… They were betrayed, I’d say,” Anatoly sighs.

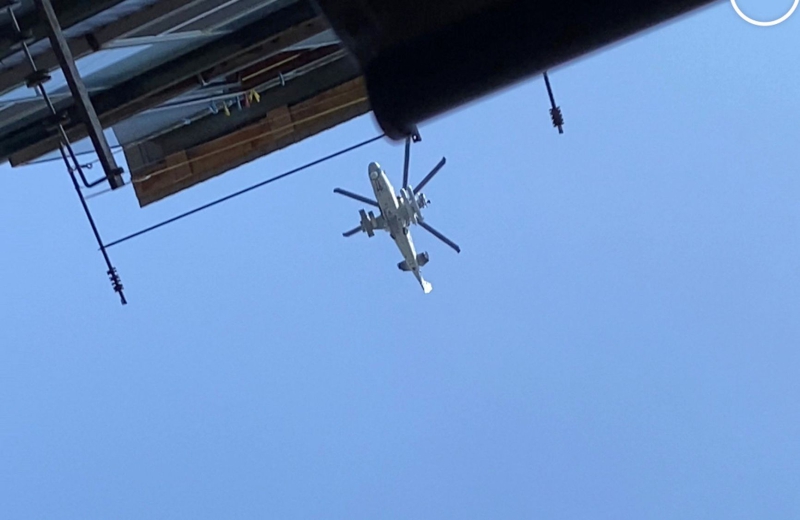

Above our heads, at an altitude of a few dozen meters, a Ka-52 attack helicopter heads for the border, followed by a Mi-28. The air raid alert goes off almost immediately. Half an hour later, another Ka-52 flies in the same direction. The helicopters return after a couple of hours.

“They are flying low to stay under the radar, normally approaching the enemy from different directions. This precaution was introduced after the strike on the airfield early on,” Anatoly comments. The Russian Air Force has no qualms about flying over the city center several times a day. When military aircraft take off, electronic warfare tools are activated, and GPS services go down. Even Google Maps is not working properly, mistaking Kursk for the nearby town of Kurchatov. Although we are standing still, the navigator app shows us somewhere in the Seym River basin, dashing at a speed of 101 km/h towards the border with Ukraine. Fifteen minutes later, everything is back to normal.

We head for the Russian Red Cross humanitarian service point on Radishcheva Street in central Kursk. To receive humanitarian aid, refugees have to make an appointment and get tokens. However, the crowd is still enormous, around a hundred people at noon. They come from Sudzha, Rylsk, Glushkovo, and Korenevo districts.

Tatiana from Rylsk caught the last bus for Kursk. On the following day, Aug. 8., the bus station was closed. “Our house was shelled. A missile hit our neighbor's house, made a hole in the roof, and burned down the house and the car. No one gave us a heads-up. We only heard news from our acquaintances, who read it online and called us. No one gives a damn about us! All we hear is lies!”

Moscow has no plans of relocating the population from territories seized by the AFU: there have been no reports of negotiations with Ukrainian units controlling Russia’s border areas. Residents of Kazachya Loknya have appealed to Vladimir Putin, the government, the Ministry of Defense, the acting governor of Kursk Oblast, and the head of the Sudzha District, asking for a green corridor to be set up to move their fellow villagers to safety. The authors of the appeal claim that many locals were killed when they attempted to evacuate in their own vehicles. For many refugees, the fate of their relatives who were left behind is their main concern.

“We have family there. They appeared in a Ukrainian video. Our 75-year-old grandpa stayed behind. He has no water or supplies. We haven’t been able to reach him for two weeks. Many have stayed. Our neighbors have an 11-month-old baby. Will he be okay?” Irina from Sudzha worries.

But while Russia has no plans of setting up humanitarian corridors, Ukraine has at least floated the idea. According to Deputy Prime Minister of Ukraine and Minister of Reintegration of Temporarily Occupied Territories Iryna Vereshchuk, the corridors between Ukraine's Sumy Oblast and Russia’s Kursk Oblast could be opened both ways. However, this would require an arrangement with the Russian side.

Refugees are actively discussing this development. Some are curious to learn more about evacuating their relatives to Ukraine but hesitate to discuss it publicly for fear of ending up in jail for “collaborating with the enemy” — which is exactly how Russian authorities interpret any contact with Ukraine.

A refugee from Sudzha asks if Ukrainian evacuation contacts are up to date and whether one can call those numbers. “I’m scared that during mop-up operations the FSB could kill everyone who stayed behind as witnesses,” the woman confesses.

The Liza Alert rapid response NGO, which helps look for missing persons, has received 779 requests and managed to process 111 of them with the status “Found. Alive.” The Russian Red Cross has received over 1,500 missing persons alerts. Most of them are for elderly people who missed the opportunity to leave or decided to stay. Alexander's parents also stayed in their village. He rescued his wife and child, but his mother and father were adamant that they were not leaving. Now the bridge his family used for their evacuation has been destroyed.

“We live between Glushkovo and Korenevo. They started packing but then decided to stay. They didn't want to go. They have livestock and chickens, and the tomatoes are ripe. They said it would blow over soon and that they’d rather sit it out.”

The parents of 17-year-old Ulyana, who appeared on video filmed by the Italian channel ROI, filed a missing person alert with both the Ukrainian and the Russian Red Cross. The girl's aunt, who is in Ukraine, spoke with the Russian independent channel Dozhd about the situation. The family is desperate to get Ulyana out of the war zone — in any direction.

During yet another air raid alert, it turns out that an air defense system is located behind the neighboring house — two missiles fired from it light up the dark sky at around midnight. That evening, my neighbors decided to leave Kursk. Among other things, they are worried by their proximity to the offices of the Border Administration of the FSB for Kursk Oblast, which is right around 200 meters from their doorstep. On another note, unlike in Belgorod, Kursk had no air raid shelters at bus stops (although the city has since begun installing some). Even two weeks into the Ukrainian incursion, air raid navigation signs mostly led to locked entryways of residential houses.

Kursk had no air raid shelters at bus stops. Air raid navigation signs mostly led to locked entryways of residential houses

In Zheleznodorozhny District, which faces a particularly high risk of drone or missile debris, shelter signs on some of the apartment buildings have actually been painted over. But many locals remain optimistic: “We live further from the border, and our air defenses are better because of the nuclear power plant in the neighboring Kurchatov,” volunteer Anatoly argues.

The lack of attention to the AFU-controlled territories from Russia’s federal television channels has obliterated the remnants of trust Kursk residents had in the Kremlin's media. The silence creates fertile soil for rumors, which many trust more than Channel One. People are talking on buses, in parks, and in courtyards.

“We’ve been told schoolchildren will study remotely until December 5. Does it mean they know how long it will last?”

“It’ll be worse in winter. How will refugees survive in tent camps? There is one such camp in Zolotukhino, and it’s already overcrowded. How can one live in a tent when it’s below zero outside?”

“An assisted living facility has been evacuated from Kursk today. That's a worrying sign. If they started to evacuate people, it means they’re preparing for something. The old folks have been moved to Chelyabinsk. Our relatives in Anapa only watch TV and have no idea what's going on here. They told me our air defense fends off all attacks, and as for the captured villages, they never heard a word!”

The house where I stay also hosts Vladislav and Lena, refugees from the village of Guevo, Glushkovo District. Another guest, Vera, is a refugee from Sudzha. I met them a few times on the bench outside. United by their common grief, the refugees stick together. Vladislav and Lena left when heavy shelling began, and the roads were already a battlefield.

“We walked 50 kilometers across forests and fields, making our way across windbreak. We found a shallow in the river and waded across. There were 14 of us, holding each other by the hand. In the end, we were all bruised and scratched, covered in blood.”

People look exhausted due to a lack of sleep. Air raid alerts howled all night long, with short breaks — more than 20 times over the last 24 hours, a record for now. “I thought of buying earplugs, but it’s sort of scary: what if I don't hear a missile hit and die in a fire,” says Vladislav, who recently managed to get his parents-in-law out of Guevo.

The air raid alert sounded more than 20 times over the past 24 hours

Guevo has been under Ukrainian fire since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. The attacks started when Russian troops made use of an abandoned ethanol plant. “They took cover there, and AFU drone operators must have noticed them. That’s when the air raids began,” Vladislav explains.

“We were afraid of fine weather because drones were at us all the time. We’d hide from them,” Lena adds. “We once went out onto the porch and saw a copter circling right above our heads. We thought we were done for… Good as dead. Nowhere to run. We had no cellar, only a pit for hiding. But the copter flew away. The operator must have taken pity on us.”

Like many others in Kursk Oblast, Guevo refugees refer to Ukrainians using the pejorative Russian word “khokhly.” However, they disapprove of the Russian government and army as well:

“What are the soldiers good for? They are all over the place, drunk and half-naked. Those wenches, our local volunteers, were always giving them food, treats, socks… ‘Our defenders, our warriors…’ What a joke!” Lyudmila recalls. “They were holed up at the plant, doing nothing, or going out for beers. Loafing about, scratching their bellies… That's what kind of defenders they were. When a fire broke out, not one of them offered to help. They were just staring at the mayhem, smoking cigarettes. Didn't even help to put it out.”

According to locals, Russian troops often use civilian vehicles without license plates to move around Kursk and the region. Indeed, we often see such cars on the road. “They want to avoid traffic tickets. They used to ride in convoys, but [Ukrainian forces] started targeting them. Now they disguise themselves as civilians,” Vladislav sighs.

Vera from Sudzha shows a video — the very one its mayor called a “hoax.” Vera disagrees with the official: “This is our town. And it's all true!” She uses Telegram channels and Western and Russian independent media to keep track of what is happening in her hometown. “My grandson installed a VPN to watch prohibited channels. And to figure out what's going on.”

According to Vera, Russian channels do not focus on what's important for the refugees: “Whenever I turn on the TV, all I hear is how eager everyone is to help and how much humanitarian aid has been distributed. And how our helicopter hit a target somewhere. What's that to me? What's happening at the border, I wonder? What's happening to our homes? To people there? To the animals left behind? When will I be back? Will I ever? There’s not a word about any of that!”

Kursk is littered with contract military service ads, promising a lump-sum payment of about $5,500 upon enlistment. There are also billboards from acting governor Alexey Smirnov's election campaign: “Deeds over words.” But Kursk Oblast residents have now had the chance to find out exactly what his words are worth. “We must not be the kind of ‘their’ people who they don’t leave behind,” Vera says bitterly.