At the end of May, Russia’s Ministry of Health approved the final version of regulations requiring annual drug screenings for all schoolchildren aged 13 and older. The legislation had been championed for years by Yevgeny Bryun, the country’s former chief narcologist. In October 2024, Bryun was sentenced to seven years in a penal colony, fined, and banned from holding any public office after a court found that he had operated a criminal cartel that secured government contracts worth 1.35 billion rubles ($18.9 million). The Insider examines how a Soviet-era narcologist developed a profitable business based on drug-testing systems while helping build one of the most repressive drug policies in the world.

In 1990, the Constitutional Oversight Committee of the USSR ruled that criminal penalties for drug use and forced “treatment” in labor camps violated human rights and contradicted the country’s fundamental law. The Soviet Union had little time left. Within a few years, forced-labor rehab centers were replaced in Russia by rehabilitation centers. The first were foreign — including the Scientologist-founded Narconon, the Christian organization Salvation Army, and the U.S. group Daytop Village. Advertisements for their services appeared in major Russian newspapers.

By the mid-1990s, domestic rehab centers began to emerge. One was the Institute for Human Adaptation, founded by Yevgeny Bryun, a doctor at Moscow’s 13th Psychiatric Hospital. Within ten years, Bryun would become a household name across Russia, regularly appearing in the media before holidays to advise the public on how to drink without getting a hangover. Twenty years later, he would be in the defendant’s chair after it was revealed that he and his close associates had spent years defrauding the state by selling overpriced blood and drug test kits.

Ptuch (Птюч) was popular Russian glossy magazine for club music enthusiasts, published from 1994 to 2003.

Goskomstat was renamed to Rosstat in 2004.

From an interview with Novye Izvestia, No. 131, June 17, 1998.

Article 228 (“Illegal production, acquisition, possession, transportation, transfer, or distribution of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances”) was included in the very first edition of the Russian Criminal Code in 1996.

Moskovskaya Pravda, No. 124, June 18, 2010.

Dark Metrics carries out independent statistical analysis of the largest drug marketplaces and vendors operating in Russia.

The Russian Birth and Death Database of the Center for Demographic Research at the New Economic School is based on demographic data from Rosstat.

Meditsinskaya Gazeta (lit. ‘Medical Newspaper’), No. 98, December 26, 2008.

“Yevgeny Bryun treats 70% of his patients for money, 30% go free of charge. He won’t be getting rich anytime soon because the nouveau riche aren’t in a hurry to help him save a generation,” lamented the author of Obshchaya Gazeta in 1995. The article, which promoted the creation of the Institute for Human Adaptation, claimed that Bryun cured “20-30% of patients with drug addiction,” while the success rate of Western programs was “up to 10%.” The source of these statistics was unclear.

Bryun also shared other questionable figures with journalists. In 1998, he claimed that one in five Russians aged 15-18 used drugs. Among the reasons for this dire state of affairs, he claimed, were horror films, action movies, the magazine Ptuch (which he called a “mouthpiece of drug culture”), and the Soviet-era cartoon Nu, Pogodi! (a Tom & Jerry style collection of animated shorts starring a wolf and rabbit).

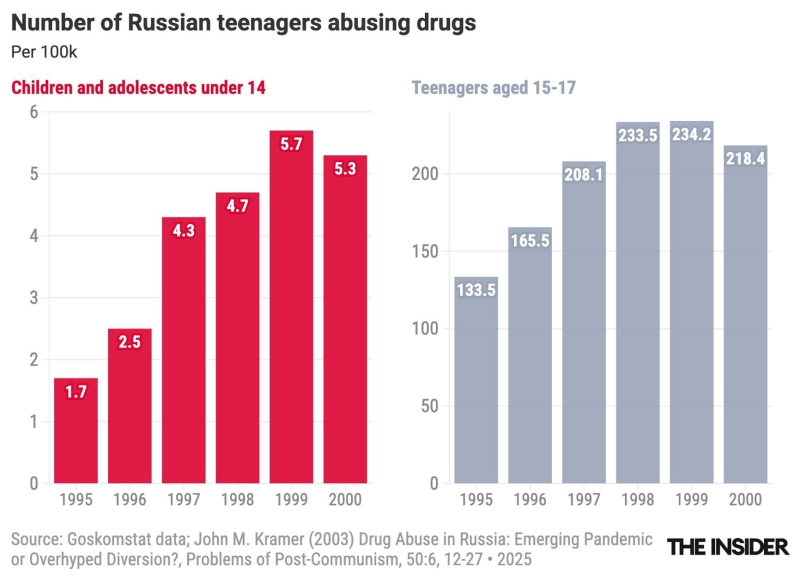

The scare stories that built Bryun’s career as Moscow’s — and eventually Russia’s — chief narcologist were not backed by data. According to a report by Russia’s State Statistics Committee (Goskomstat), in 1995 only 13 out of every 10,000 teens aged 15-17 actually used drugs. By 2000, the number rose to 22 per 10,000, or 0.2%. That’s 100 times less than the “one in five” figure Bryun claimed.

Ptuch (Птюч) was popular Russian glossy magazine for club music enthusiasts, published from 1994 to 2003.

Goskomstat was renamed to Rosstat in 2004.

From an interview with Novye Izvestia, No. 131, June 17, 1998.

Article 228 (“Illegal production, acquisition, possession, transportation, transfer, or distribution of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances”) was included in the very first edition of the Russian Criminal Code in 1996.

Moskovskaya Pravda, No. 124, June 18, 2010.

Dark Metrics carries out independent statistical analysis of the largest drug marketplaces and vendors operating in Russia.

The Russian Birth and Death Database of the Center for Demographic Research at the New Economic School is based on demographic data from Rosstat.

Meditsinskaya Gazeta (lit. ‘Medical Newspaper’), No. 98, December 26, 2008.

A more detailed 1996 study on psychoactive substance use among Moscow schoolchildren found that 4% of seventh-graders had sniffed glue or solvents in the past year and 2.4% had smoked marijuana. No use of other drugs was detected in that group. Among ninth-graders, 10% reported smoking marijuana, 6% had mixed alcohol with tranquilizers, and 2.3% said they had tried heroin. At the same time, 81% of ninth-graders regularly consumed alcohol. Between 60% and 80% of students expressed disapproval of drug use and said their knowledge of drugs came primarily from the media.

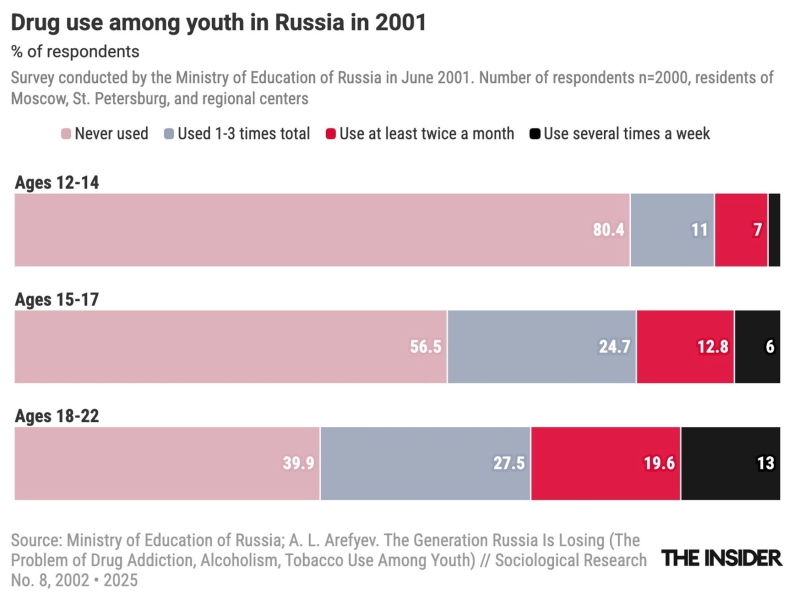

A 2001 survey by the Ministry of Education found that nearly 13% of high school seniors said they used drugs at least twice a month — in most cases cannabinoids.

Ptuch (Птюч) was popular Russian glossy magazine for club music enthusiasts, published from 1994 to 2003.

Goskomstat was renamed to Rosstat in 2004.

From an interview with Novye Izvestia, No. 131, June 17, 1998.

Article 228 (“Illegal production, acquisition, possession, transportation, transfer, or distribution of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances”) was included in the very first edition of the Russian Criminal Code in 1996.

Moskovskaya Pravda, No. 124, June 18, 2010.

Dark Metrics carries out independent statistical analysis of the largest drug marketplaces and vendors operating in Russia.

The Russian Birth and Death Database of the Center for Demographic Research at the New Economic School is based on demographic data from Rosstat.

Meditsinskaya Gazeta (lit. ‘Medical Newspaper’), No. 98, December 26, 2008.

Despite his blatant manipulation of the data, by 1998 Bryun had effectively become Moscow’s chief narcologist. He soon launched a crackdown on drug users across the city.

In the spring of 1999, Moscow psychiatrists began receiving visits from police officers demanding information on patients suffering from drug addiction. Doctors were unsure whether cooperation represented a violation of doctor-patient privilege, but law enforcement was insistent and often extracted the information they wanted. Ostensibly, the purpose was to combat drug trafficking, but in reality, some regular patients were arrested after being “reported” by their doctors.

Police were acting under a secret order developed personally by Bryun during his time in the Moscow Health Committee. Reporters from Vechernyaya Moskva obtained the document, which stated that the committee, along with the Moscow police department, had developed a system of “mutual information exchange on individuals who engage in non-medical drug use” and had also conducted a “complete review of underage drug addicts.”

Ptuch (Птюч) was popular Russian glossy magazine for club music enthusiasts, published from 1994 to 2003.

Goskomstat was renamed to Rosstat in 2004.

From an interview with Novye Izvestia, No. 131, June 17, 1998.

Article 228 (“Illegal production, acquisition, possession, transportation, transfer, or distribution of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances”) was included in the very first edition of the Russian Criminal Code in 1996.

Moskovskaya Pravda, No. 124, June 18, 2010.

Dark Metrics carries out independent statistical analysis of the largest drug marketplaces and vendors operating in Russia.

The Russian Birth and Death Database of the Center for Demographic Research at the New Economic School is based on demographic data from Rosstat.

Meditsinskaya Gazeta (lit. ‘Medical Newspaper’), No. 98, December 26, 2008.

replied that “the strictness of our laws is offset by their total non-enforcement.” He promised drug users who sought treatment voluntarily that he would not report them to the police. In other cases, however, the chief narcologist of Moscow had no qualms about breaching confidentiality:

“In some cases, the police inform us that the drug addict is in a psychotic state, trying to tie his shoelaces — that is, trying to kill himself — attacking distraught parents, extorting money from them for a fix. We have every right to hospitalize him. During the 10-14 days it takes to resolve the psychosis, the men in uniform are free to obtain information from us. After a couple of weeks, the guy has the right to anonymous treatment.”

Ptuch (Птюч) was popular Russian glossy magazine for club music enthusiasts, published from 1994 to 2003.

Goskomstat was renamed to Rosstat in 2004.

From an interview with Novye Izvestia, No. 131, June 17, 1998.

Article 228 (“Illegal production, acquisition, possession, transportation, transfer, or distribution of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances”) was included in the very first edition of the Russian Criminal Code in 1996.

Moskovskaya Pravda, No. 124, June 18, 2010.

Dark Metrics carries out independent statistical analysis of the largest drug marketplaces and vendors operating in Russia.

The Russian Birth and Death Database of the Center for Demographic Research at the New Economic School is based on demographic data from Rosstat.

Meditsinskaya Gazeta (lit. ‘Medical Newspaper’), No. 98, December 26, 2008.

Bryun’s stance stemmed from his belief that nearly all drug users were also drug dealers:

“The Criminal Code article isn’t worded well. But that doesn’t mean such a law shouldn’t exist. A drug addict is almost always two people in one: both user and dealer. As for whether it’s a disease — that’s a gray area. Only an experienced doctor can determine when the craving becomes pathological. And of course, it should be the doctor, not the police, who decides that… A sick person should absolutely not face criminal charges for drug use. I’ll go further: we are now trying to convince lawmakers to equate drug addiction with mental illness.”

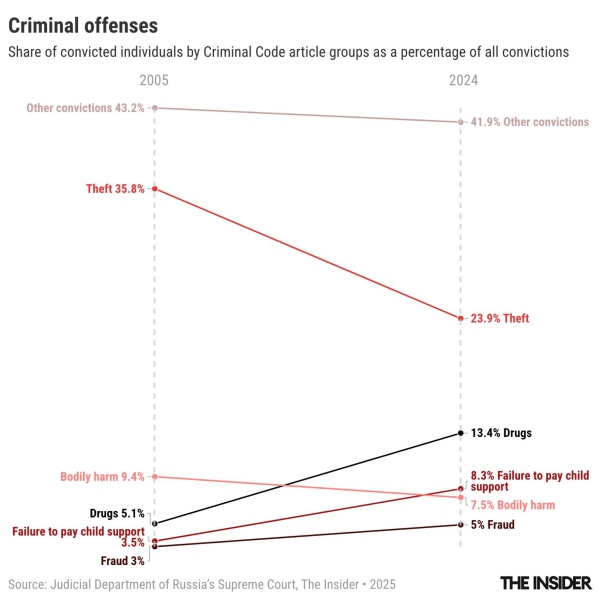

This approach laid much of the groundwork for Russia’s punitive drug policies — in both the medical and law enforcement spheres. For many years, drug-related articles have ranked second in Russia by number of convictions. In 2024, according to the country’s Ministry of Justice, more than 68,500 people were convicted under such charges. Of those, 70% were drug users who had been sentenced under laws that do not require intent to distribute.

Ptuch (Птюч) was popular Russian glossy magazine for club music enthusiasts, published from 1994 to 2003.

Goskomstat was renamed to Rosstat in 2004.

From an interview with Novye Izvestia, No. 131, June 17, 1998.

Article 228 (“Illegal production, acquisition, possession, transportation, transfer, or distribution of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances”) was included in the very first edition of the Russian Criminal Code in 1996.

Moskovskaya Pravda, No. 124, June 18, 2010.

Dark Metrics carries out independent statistical analysis of the largest drug marketplaces and vendors operating in Russia.

The Russian Birth and Death Database of the Center for Demographic Research at the New Economic School is based on demographic data from Rosstat.

Meditsinskaya Gazeta (lit. ‘Medical Newspaper’), No. 98, December 26, 2008.

While the total number of criminal convictions in Russia has dropped 42% over the past 20 years — from 879,000 to 512,000 — drug convictions have steadily risen: from 40,000 in 2005 to 68,500 in 2024.

Successful drug policies in many countries are built on three pillars: harm reduction programs, opioid substitution therapy, and widespread availability of naloxone — an antidote to opioid overdose. Yevgeny Bryun consistently opposed all three, says Maksim Malyshev, a former coordinator of social workers at the nonprofit Andrey Rylkov Foundation.

“Bryun is, of course, a complicated figure. There were some good things. He did a lot to support the communities of Narcotics Anonymous and Alcoholics Anonymous,” said Malyshev. “But we all understand that approach isn’t for everyone, right? Bryun had this tunnel-vision idea of total abstinence. Either you quit drugs that way, or, I don’t know, you’re supposed to just die.”

Ptuch (Птюч) was popular Russian glossy magazine for club music enthusiasts, published from 1994 to 2003.

Goskomstat was renamed to Rosstat in 2004.

From an interview with Novye Izvestia, No. 131, June 17, 1998.

Article 228 (“Illegal production, acquisition, possession, transportation, transfer, or distribution of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances”) was included in the very first edition of the Russian Criminal Code in 1996.

Moskovskaya Pravda, No. 124, June 18, 2010.

Dark Metrics carries out independent statistical analysis of the largest drug marketplaces and vendors operating in Russia.

The Russian Birth and Death Database of the Center for Demographic Research at the New Economic School is based on demographic data from Rosstat.

Meditsinskaya Gazeta (lit. ‘Medical Newspaper’), No. 98, December 26, 2008.

“Either you quit drugs that way, or, I don’t know, you’re supposed to just die.”

While serving as Moscow’s — and, later, Russia’s — top narcologist, Bryun helped block access to both substitution therapy and harm reduction programs for drug users, opposing NGOs that promoted such initiatives. “And we know the only effective method for preventing HIV is harm reduction,” Malyshev said. “My biggest grievance with Bryun and others like him is that they contributed heavily to the HIV epidemic in Russia.”

Harm reduction programs include the street distribution of condoms, disinfectants, and sterile syringes. In 2016, Bryun labeled such efforts “propaganda for drug use,” adding that: “The medical community generally takes a skeptical view of syringe distribution on the street, because by distributing these materials, we draw attention to this sphere from citizens who might never have thought about it otherwise.”

But Bryun’s statement was false. By that time, the medical consensus — based on decades of global evidence — had already confirmed that such programs save lives and do not lead to increased drug use.

Ptuch (Птюч) was popular Russian glossy magazine for club music enthusiasts, published from 1994 to 2003.

Goskomstat was renamed to Rosstat in 2004.

From an interview with Novye Izvestia, No. 131, June 17, 1998.

Article 228 (“Illegal production, acquisition, possession, transportation, transfer, or distribution of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances”) was included in the very first edition of the Russian Criminal Code in 1996.

Moskovskaya Pravda, No. 124, June 18, 2010.

Dark Metrics carries out independent statistical analysis of the largest drug marketplaces and vendors operating in Russia.

The Russian Birth and Death Database of the Center for Demographic Research at the New Economic School is based on demographic data from Rosstat.

Meditsinskaya Gazeta (lit. ‘Medical Newspaper’), No. 98, December 26, 2008.

Despite resistance from lawmakers and Ministry of Health officials, volunteers in Russia continue to carry out harm reduction efforts.

A white minivan from a charitable organization sits unnoticed in a parking lot between gray apartment blocks in the Maryino district of Moscow. Standing nearby are a man in a coat with a dog on a leash and a young man in black sweatpants and a hoodie that hides his face. Both are drug users from a nearby building. They’ve come to pick up free syringes and condoms.

Inside the van are three volunteers, along with two young women who have come to get tested for blood-borne infections. This helps raise awareness about their health and allows those who test positive to begin treatment in time, the volunteers explain to The Insider. One worker applies reagents to a test strip, then pricks a woman’s finger with a small lancet. He squeezes out a few drops of blood and hands her a tissue.

“The hardest part is telling someone their test is positive. That’s always the most difficult for me,” said volunteer Misha [names have been changed at the sources' request]. “People react very differently. Some go into shock, others cry and can’t believe it.”

While the patient waits — the test takes about 10 minutes — several more people approach the van to ask for condoms. “Handing out protection helps stop the spread of sexually transmitted diseases,” explained another volunteer, Miron. “We get all kinds of people: sex workers, college students who can’t afford expensive condoms. The fact that they come at all is a good sign. It means they’re thinking about protection. Some don’t use anything at all.”

In addition to clean syringes and condoms, the volunteers distribute antiseptic ointments and bandages:

“This makes people think about themselves, about their health. They realize they need to care for themselves. We tell them how to get help. Sometimes that’s the first step toward quitting drugs.”

Due to the lack of state harm reduction programs and the fear of legal punishment, many users resort to dangerous practices — sharing needles or using communal equipment to prepare drugs. This leads to the spread of HIV and hepatitis, epidemics made worse by the scarcity of affordable condoms.

“You can hate drug users and wish them dead, and that’s basically what’s happening in Russia now,” said one volunteer. “But the absence of harm reduction programs ends up hurting people outside the so-called ‘risk groups’ — people who don’t use drugs, who aren’t sex workers, just regular folks like you and me.”

Ptuch (Птюч) was popular Russian glossy magazine for club music enthusiasts, published from 1994 to 2003.

Goskomstat was renamed to Rosstat in 2004.

From an interview with Novye Izvestia, No. 131, June 17, 1998.

Article 228 (“Illegal production, acquisition, possession, transportation, transfer, or distribution of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances”) was included in the very first edition of the Russian Criminal Code in 1996.

Moskovskaya Pravda, No. 124, June 18, 2010.

Dark Metrics carries out independent statistical analysis of the largest drug marketplaces and vendors operating in Russia.

The Russian Birth and Death Database of the Center for Demographic Research at the New Economic School is based on demographic data from Rosstat.

Meditsinskaya Gazeta (lit. ‘Medical Newspaper’), No. 98, December 26, 2008.

The absence of harm reduction programs ends up hurting people outside risk groups.

Volunteers help people who test positive for HIV connect with psychologists and receive guidance on where to seek treatment, but the process isn’t easy. “The biggest problem right now is stigma,” said Misha. “For someone with HIV, even seeking basic medical help at a clinic can be difficult. Doctors can be cruel and say horrible things.”

Volunteers currently operate in both northern and southern Moscow and plan to expand outreach to more neighborhoods. “That’s tough — no one knows us in other areas. We have to explain who we are, and we can’t exactly advertise,” said Miron. “It’s also a safety issue for our volunteers and the people who come to us. There are a lot of hostile people, not just toward drug users but toward those who help them. They tell us we have no right to be there, to get out.”

Bryun and his allies — including Moscow City Duma MP Lyudmila Stebenkova and Moscow’s chief HIV specialist Alexei Mazus — routinely spoke with disdain about such volunteer efforts. “These forces are engaged in active propaganda funded by Western charitable organizations, shaping a tolerant public attitude toward drug use. In various cities across Russia and the CIS, even professionals show sympathy toward harm reduction and methadone programs, which complicates the development of a unified state policy and methodology for reducing drug demand,” Bryun said in 2010.

In 2016, Bryun told Novaya Gazeta that his “Moscow Narcology Service” had its own outreach program: “There’s an alternative project, a motivational street service. They don’t distribute syringes; they share information about available treatment options in city clinics.”

But drug users have ample reason to avoid state-run clinics — stigma and potential punitive measures chief among them. Patients have reported physical abuse by medical staff, resulting in injuries. Caregivers have also demonstrated a marked disregard for patients’ medical conditions.

“[One patient] warned doctors he was intolerant to haloperidol,” said Malyshev. “But they injected him with the antipsychotic anyway. He slept for days, then struggled to walk. His legs kept giving out. He stumbled, fell, hurt himself. On the tenth day, he hit his head so hard he was bleeding. An ambulance took him to a regular hospital. They referred him to a trauma specialist.”

Natalia, a former staff member at a Moscow rehab center, said such practices were widespread: “Tranquilizers were for those in withdrawal. Half an hour after getting the shot, they’d be knocked out. And that’s how it went until the withdrawal passed.”

Natalia also said administrators also misled patients: “They came here thinking it was a resort. Our head doctor ran ads claiming we had a pool, a tennis court, entertainment, that patients were kept busy, that the treatment was innovative. So kids were sent to us from all over. They’d show up and ask, ‘Where’s the pool?’ But it was like a prison. A locked facility. No one got in or out unless I opened the door. Treatment lasted two to three months.”

Another reason people avoid treatment is the mandatory narcological registry. Being added to it can mean losing one’s job, driver’s license, or other rights.

“If you ask narcologists or officials, they’ll say the registry no longer exists, that now it’s just ‘preventive monitoring.’ And they’ll insist it’s not really a registry,” Malyshev said. “But in practice, nothing has changed. People are afraid of losing their rights — especially parents. They’re afraid of child protective services.”

Another problem involves official residency. Many Russians who move to a different city face obstacles when it comes to establishing an official address, leaving them ineligible to receive government services at their new place of physical residence.

“One of our clients urgently needed rehab. He was heavily using synthetic cathinones — ‘bath salts’ — and was barely holding it together,” said Malyshev. “He had documents confirming his treatment, his immune status. But at Moscow’s 17th Narcology Hospital, the doctor turned us away, saying that under new leadership, as of March, they don’t admit non-Muscovites. Only in emergency cases — and even that’s hit or miss.”

In such cases, volunteers try to take patients to the National Narcology Research Center, which is federally funded. But the waitlist there can be a month long, Malyshev said.

Ptuch (Птюч) was popular Russian glossy magazine for club music enthusiasts, published from 1994 to 2003.

Goskomstat was renamed to Rosstat in 2004.

From an interview with Novye Izvestia, No. 131, June 17, 1998.

Article 228 (“Illegal production, acquisition, possession, transportation, transfer, or distribution of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances”) was included in the very first edition of the Russian Criminal Code in 1996.

Moskovskaya Pravda, No. 124, June 18, 2010.

Dark Metrics carries out independent statistical analysis of the largest drug marketplaces and vendors operating in Russia.

The Russian Birth and Death Database of the Center for Demographic Research at the New Economic School is based on demographic data from Rosstat.

Meditsinskaya Gazeta (lit. ‘Medical Newspaper’), No. 98, December 26, 2008.

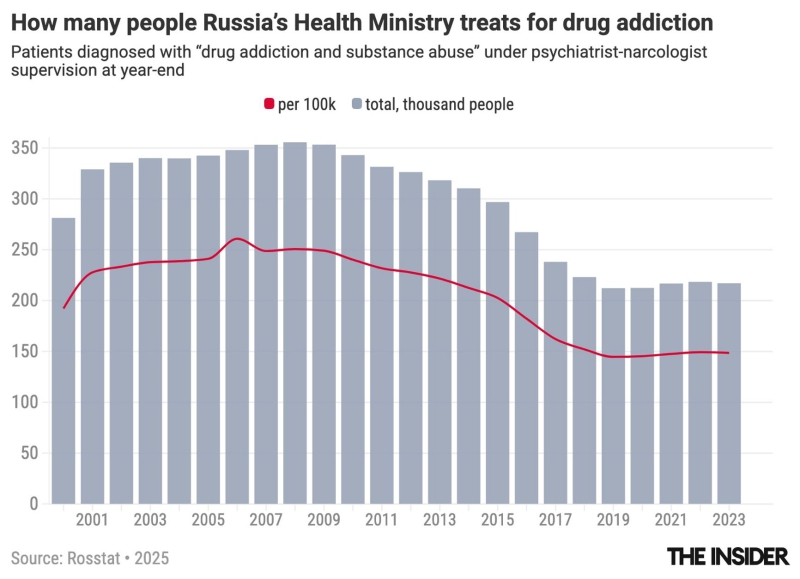

However, official statistics are unlikely to reflect the real number of people who use drugs. For instance, in 2024, the Moscow Health Department reported registering 21,700 cases of “patients with drug dependence syndrome.” Meanwhile, analysts from the Telegram channel Dark Metrics estimated that Muscovites left at least 1.5 million reviews related to drug purchases during the same period — and only a fraction of customers typically leave reviews.

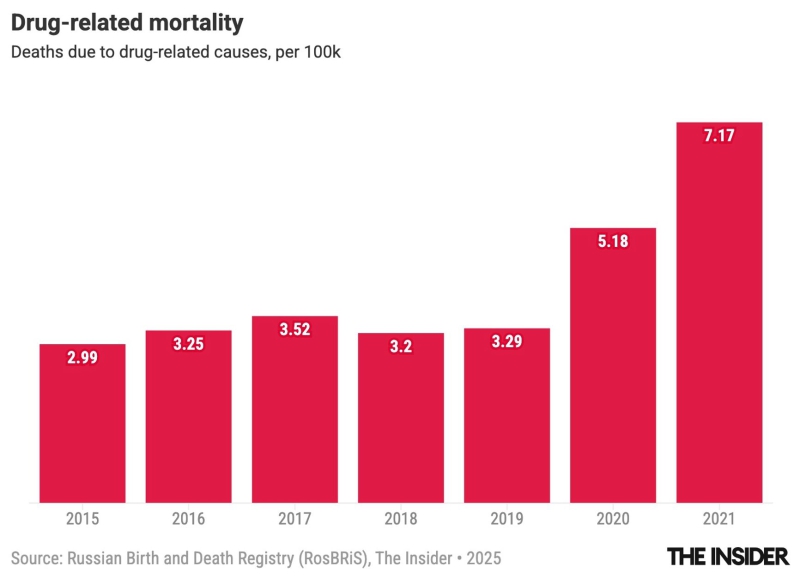

Data on those seeking medical treatment do not include patients at private clinics, meaning that while official documents speak of a decline in the number of patients at public narcology centers, the actual number is likely increasing. Drug-related mortality is also rising. The Insider analyzed data from the Russian Birth and Death Registry (RosBRiS) showing that over 10,000 people died from drug use in 2021 — a 2.4-fold increase compared to 2015.

Ptuch (Птюч) was popular Russian glossy magazine for club music enthusiasts, published from 1994 to 2003.

Goskomstat was renamed to Rosstat in 2004.

From an interview with Novye Izvestia, No. 131, June 17, 1998.

Article 228 (“Illegal production, acquisition, possession, transportation, transfer, or distribution of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances”) was included in the very first edition of the Russian Criminal Code in 1996.

Moskovskaya Pravda, No. 124, June 18, 2010.

Dark Metrics carries out independent statistical analysis of the largest drug marketplaces and vendors operating in Russia.

The Russian Birth and Death Database of the Center for Demographic Research at the New Economic School is based on demographic data from Rosstat.

Meditsinskaya Gazeta (lit. ‘Medical Newspaper’), No. 98, December 26, 2008.

Most of these deaths were preventable. They typically resulted from opioid overdoses — a condition that, in much of the world, is treated with naloxone. But in Russia, naloxone is only available by prescription.

“This is standard practice worldwide. Even in conservative countries, naloxone is readily available to drug users. In Canada and many Western European nations, you can get it for free at pharmacies — it costs next to nothing,” said Alexei Lakhov, former development director at the Humanitarian Action Foundation, creator of the Drugmap project, and a member of the Steering Committee of the Eurasian Harm Reduction Association.

Naloxone distribution is a key component of harm reduction, as are free syringe programs, condom distribution, and education on HIV and hepatitis. Although Bryun never publicly denounced naloxone outright, purchasing it in Russia has always been difficult: the drug is sold only with a prescription and is often unavailable in pharmacies. Even emergency medical teams frequently do not have it on hand despite regulations requiring them to carry it.

Ptuch (Птюч) was popular Russian glossy magazine for club music enthusiasts, published from 1994 to 2003.

Goskomstat was renamed to Rosstat in 2004.

From an interview with Novye Izvestia, No. 131, June 17, 1998.

Article 228 (“Illegal production, acquisition, possession, transportation, transfer, or distribution of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances”) was included in the very first edition of the Russian Criminal Code in 1996.

Moskovskaya Pravda, No. 124, June 18, 2010.

Dark Metrics carries out independent statistical analysis of the largest drug marketplaces and vendors operating in Russia.

The Russian Birth and Death Database of the Center for Demographic Research at the New Economic School is based on demographic data from Rosstat.

Meditsinskaya Gazeta (lit. ‘Medical Newspaper’), No. 98, December 26, 2008.

Naloxone, a medication used to rapidly reverse opioid overdoses, is sold in Russia only with a prescription and is often unavailable in pharmacies.

In 2016, as part of his attacks on harm reduction volunteers and NGOs, Bryun told Moscow media that naloxone would be distributed through public narcology clinics. Unlike the anonymous access offered by volunteer groups, patients at state centers had to visit during business hours, register, and be added to the narcological registry. That year, the Moscow Scientific and Practical Center for Narcology, headed by Bryun, purchased 3,000 packs of naloxone, but procurement records suggest that this was a one-off.

Bryun remained skeptical about the life-saving potential of this safe, low-cost medication. In a 2016 interview with the independent media outlet Takie Dela, he was asked why naloxone couldn’t be sold over the counter — a reform that would allow bystanders to save the lives of overdose victims. He replied:

“They still wouldn’t make it in time. Death is instantaneous.”

In 2018, naloxone production in Russia stopped altogether for a period of several months when the sole domestic manufacturer, the Moscow Endocrine Plant, was unable to secure imported raw materials. The company also expressed doubts about the profitability of producing naloxone due to the fact that those who needed it most couldn’t access it without a prescription.

According to Maksim Malyshev, detox services in state-run narcology clinics are inadequate:

“They’re injected with haloperidol and aminazine — outdated drugs with loads of side effects. We talk to a lot of people who use drugs, and very few are satisfied with the quality of treatment. When they come seeking help, they expect care, pain relief, some kind of support, but they don’t get it.”

Opioid substitution therapy using methadone or buprenorphine could help people taper off opioids gradually. International organizations including the WHO and the UN recognize substitution therapy as the “gold standard” of treatment. It is credited with reducing crime, improving social reintegration, and lowering mortality among people who use opioids.

Yet Bryun continued to insist that methadone therapy does not treat addiction, claiming it merely maintains it. In his view, this conflicted with the goals of Russia’s state drug policy. He and other Health Ministry officials also claimed that substitution therapy posed risks of illegal drug diversion.

In its place, they promoted detox and rehabilitation methods that excluded medical substitution. These included spiritually based programs or superficial “social adaptation” efforts, neither of which are supported by evidence-based medicine.

Without access to substitution therapy, patients are forced to quit entirely and immediately — a process known to cause relapse. Calls by human rights advocates for the implementation of substitution therapy in Russia have long met with resistance from the country’s Health Ministry.

“All our proposals — on substitution therapy, on expanding harm reduction — were rejected,” said Malyshev. “And it wasn’t just Bryun doing the rejecting. We’d get meaningless replies: ‘Thank you for your active participation,’ and that was it. Bryun had a deeply negative view of both harm reduction and substitution therapy. I don’t know where he picked it up, but the nonsense he pushed that this is some Western plot to corrupt society was absurd.”

Ironically, Bryun adopted many of his non-mainstream views from the West, specifically from John Walters, the former U.S. “drug czar” under President George W. Bush (2001-2009). Walters claimed that coerced drug treatment “works at least as well as voluntary treatment” and that harm reduction policies gave the message that “society has given up on the addict.” Bryun later echoed Walters, saying:

“Teaching someone with [an] addiction to use drugs safely is practically impossible… That’s why all work, including harm reduction efforts, should be carried out only in clinical addiction treatment facilities.”

Bryun made that statement in late 2008 at the “HIV/AIDS in Developed Countries” conference organized by Moscow’s city government. Then-Mayor Yury Luzhkov went even further, arguing that harm reduction “conflicted with Russia’s legal, moral, and cultural norms.” Just months after the conference, Bryun was appointed chief freelance psychiatrist-narcologist of the Ministry of Health.

Since the late 1990s, Bryun had repeatedly claimed that most teenagers in Russia were using drugs regularly. After becoming Moscow’s chief narcologist, he proposed to the City Duma that all students undergo drug testing.

This idea, like others in his policy playbook, appears to have been inspired by George W. Bush’s “drug czar.” When Walters first advocated for school drug testing in America, the response from society was largely negative, but he defended the practice by arguing that treating the “disease” outweighed the right to privacy. He framed mandatory testing as a prerequisite for “responsible behavior.”

Bryun used similar rhetoric, claiming that early testing would help identify students using drugs before they became addicted. He also put forward the idea that fear of being tested would deter youth from using narcotics altogether.

Medical research does not support such claims. The American Academy of Pediatrics (APA) has repeatedly stated that school-based drug testing does not prevent substance use. Even if students are using drugs, they often find ways to avoid detection. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction has found that such measures may, in some cases, exacerbate the issue — and it generally offers little to no benefit in return.

Nevertheless, in 2013, Russia adopted legislation promoted by Bryun requiring that high school students be tested for drugs at least once a year. The law allowed for voluntary participation, which disappointed Bryun. A year later, at a meeting with Vladimir Putin, Russia’s equivalent of the “drug czar” pressed for an expansion of the program. As justification, he cited the bizarre example of “a drug addict heating a spoon of heroin over an open flame directly at an oil refinery.”

The most recent version of the student drug-testing rules was approved on May 30, 2025, and despite Bryun’s wishes, students or their parents must still provide informed consent. Still, despite repeated claims over the years that testing was anonymous, in practice results are entered into the child’s medical record.

“He won't get rich anytime soon,” was how some media outlets wrote about Bryun back in 1995. But he did try. One such attempt eventually landed him in court: Russia’s chief narcologist had lobbied for mandatory testing of drivers for “chronic alcoholism,” with the tests supplied by companies linked to him.

In the fall of 2019, thousands of Russians lined up at addiction clinics across the country to obtain the medical certificate required for a driver’s license. Within months, the cost of the procedure was set to increase tenfold — from 450 rubles to over 5,000. Under a plan championed by Bryun, drivers would be required to take a test for alcohol abuse. For several years prior, he had been lobbying for the installation of alcohol testing systems in clinics — first in Moscow, then across other Russian cities.

Ptuch (Птюч) was popular Russian glossy magazine for club music enthusiasts, published from 1994 to 2003.

Goskomstat was renamed to Rosstat in 2004.

From an interview with Novye Izvestia, No. 131, June 17, 1998.

Article 228 (“Illegal production, acquisition, possession, transportation, transfer, or distribution of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances”) was included in the very first edition of the Russian Criminal Code in 1996.

Moskovskaya Pravda, No. 124, June 18, 2010.

Dark Metrics carries out independent statistical analysis of the largest drug marketplaces and vendors operating in Russia.

The Russian Birth and Death Database of the Center for Demographic Research at the New Economic School is based on demographic data from Rosstat.

Meditsinskaya Gazeta (lit. ‘Medical Newspaper’), No. 98, December 26, 2008.

The machines used to conduct the tests were purchased from formally independent companies. However, they were all linked to people close to Bryun: Vladimir Yakushev, vice president of both the Russian Narcologists Association and the Russian Narcotic League; Elena Yakusheva, Vladimir’s wife; Pavel Loshakov, a former MP for United Russia; Loshakov’s daughter Olesya; and businessmen Denis Kuteynikov, Sergey Vasilyev, and Denis Shachenkov.

The public outcry around the costly certificates eventually reached President Putin himself. “It’s nonsense,” Putin said. “The minimum wage is 11,280 rubles. That’s what 3.2 million people earn — and employers often underpay illegally. If the certificate costs 5,000 rubles, that’s half a person’s salary!”

Shortly afterward, both Bryun and Yakushev came under official scrutiny. State Duma deputy Dmitry Ionin requested that the Federal Antimonopoly Service (FAS) investigate whether narcologists were financially linked to the test suppliers, and the new testing policy was postponed until March 2022.

In August 2022, FAS announced that it had uncovered a cartel. Yakushev, Kuteynikov, and others had colluded for years, submitting bids for the same government tenders for test kits and colluding to determine who would “win.” One week later, Bryun was arrested. On October 17, 2024, Moscow’s Kuzminsky District Court sentenced him, Yakushev, and other members of the scheme to between four and seven years in prison for large-scale fraud.

According to FAS estimates, between 2017 and 2019 the cartel earned 125.7 million rubles (roughly $2 million at the time), and a 2019 investigation by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty found that companies tied to Bryun and Yakushev had earned 572 million rubles from government contracts over five years (around $9 million).

Despite the criminal convictions, the cartel’s companies remain in business. As of July 2025, six of the 11 firms named by FAS were still active and winning state contracts. The Insider also found that longtime pharmaceutical associate Sergey Vasilyev, along with Yakushev’s wife Elena and his children Alexander and Irina, have since founded several new companies. Since 2022, these entities have signed government contracts worth 1.35 billion rubles ($16.6 million based on the current exchange rate) — mainly for drug tests, reagents for alcohol screening, and maintenance of testing systems promoted by Yevgeny Bryun.

A full list of companies linked to Yevgeny Bryun, Vladimir Yakushev, and the FAS investigation is available on The Insider’s GitHub.

Ptuch (Птюч) was popular Russian glossy magazine for club music enthusiasts, published from 1994 to 2003.

Goskomstat was renamed to Rosstat in 2004.

From an interview with Novye Izvestia, No. 131, June 17, 1998.

Article 228 (“Illegal production, acquisition, possession, transportation, transfer, or distribution of narcotic drugs or psychotropic substances”) was included in the very first edition of the Russian Criminal Code in 1996.

Moskovskaya Pravda, No. 124, June 18, 2010.

Dark Metrics carries out independent statistical analysis of the largest drug marketplaces and vendors operating in Russia.

The Russian Birth and Death Database of the Center for Demographic Research at the New Economic School is based on demographic data from Rosstat.

Meditsinskaya Gazeta (lit. ‘Medical Newspaper’), No. 98, December 26, 2008.