Over the last few months, the joint efforts of Russian law enforcement agencies and ultra-right bullies have resulted in the closure of LGBTQ+ friendly clubs all over Russia. The most infamous episode of this campaign was the March raid on Orenburg’s LGBT club Pose, which was followed by Russia’s first criminal case against LGBTQ+ community members on the charges of “organizing an extremist group.” The club owner and two employees were arrested and placed in custody. As The Insider’s correspondent found out, not only former Pose patrons, but also representatives of visually distinctive subcultures such as the anime fandom, no longer feel safe in Orenburg. Even worse, they are afraid to go to the police, as recent Russian legislation has made them outlaws. It is a situation similar to Soviet times, when anyone whose fashion choices veered from the “norm” could find themselves in trouble with the authorities.

Repression against Russia’s LGBTQ+ community intensified with the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Late 2022 saw a tightening of the Russian law banning the propaganda of so-called “non-traditional sexual relations,” and in early 2023, the law began to be widely enforced. A ban on gender transition followed in July 2023, and in late 2023 Russia's Supreme Court labeled the non-existent “international LGBT movement” as an extremist group. The new legislation triggered a wave of raids on LGBTQ+ establishments all over Russia.

The raid on Orenburg's Pose club received the most media attention. On the night of Mar. 9, 2024, law enforcement officers burst into the crowded club, shouting “Get down on the floor!” Patrons were made to lie face down; some were interrogated. No one was arrested that night, but the police subsequently detained the club's artistic director, Alexander Klimov, administrator Diana Kamilyanova, and owner Vyacheslav Khasanov. The first members of Russia's LGBTQ+ community to be arrested on extremism charges, they are now facing up to 10 years in prison.

Pose guests who were present at the time of the raid still fear for their safety and freedom, as law enforcement agencies now have their personal details.

“You can’t even go outside without fearing that someone may push you to the ground at any moment and go unpunished,” says Sasha, an Orenburg resident and Pose patron whose name has been changed for safety reasons. “No one is active in our chat anymore. It is no longer functional, as everyone is scared and silent. Our former admin has stepped down. He simply left the chat one day and said that he was scared, that he was in danger.”

“Many were caught on video. Those who stood out were photographed, and their photos were distributed across news channels,” Sasha recalls. “There were many young people on the brink of adulthood. Now the entire city has seen their faces, and everyone at work, at college, and at home knows about them.”

Club guests are afraid that their photos and personal data might end up not only with the police but also in the hands of homophobic activists from ultra-right groups such as “Russkaya Obshchina,” the “community of ethnic Russians.” This nationalist network became active throughout Russia in 2022, coordinating its activities through Telegram channels. Its agenda is centered on “Orthodox Christian faith,” “protecting” the ethnic Russian population, “fighting migrants,” and supporting Russia’s war in Ukraine. The group cooperates with law enforcement agencies, reporting “offenders” and participating in raids.

Club guests are afraid that their photos and personal data might end up not only with the police, but also in the hands of homophobic activists from ultra-right groups

It was Orenburg’s Russkaya Obshchina cell that filed a complaint against Pose, which led to a raid on the club and criminal proceedings against its owner and staff. Some of the club patrons interviewed by The Insider claim that the raid was carried out by the ultra-right activists themselves — apparently with permission from the authorities. Footage of the raid was first published on Obshchina’s Telegram channel.

Like other interviewees, Sasha admits that the raid has exacerbated fears for her safety. “I cannot overcome the state of existential crisis and profound paranoia. I only go online using Tor and two VPN services, and it's been like that for a year. First, the ban on gender transition, then the recognition of LGBT as an extremist group, then the raid against the club,” Sasha recounts.

Pose is located in the northeastern part of Orenburg, some three kilometers from the city center. A two-floor building with an entrance from the side, the club stands in a row of private houses, facing five-story apartment blocks and the Vocational School of Humanities and Engineering. By day, it is almost empty. Today, a new establishment has replaced Pose, and nothing there offers any reminder of the raids. The bus stop sports a large “Down with the government!” graffiti message, the work of locals dissatisfied with the compensation package provided following a recent flood — only about $1,000 per person. Communal workers have done a slipshod job painting over the graffiti, while largely ignoring the innumerable ads for online narcotics shops and QR codes leading to Darknet websites. After all, such advertisements dot the walls of buildings all over town.

“[Pose] was a mixed space that welcomed everyone, not just LGBT folks. I think most of the audience were straight people who came to see the drag show, which was the main attraction,” says Maria, who works not far from where the club was (her name has also been changed). She does not identify as a member of the LGBTQ+ community but often met up with her friends at Pose after work.

Maria struggles to understand why the authorities targeted this particular club. According to her, it was “as appropriate as it gets,” and nothing even remotely offensive happened there: “Whenever the guard saw two girls kissing, he would come up and ask them to stop. The only dubious thing was the afterparties, when guests could start dancing on tables, and the club workers drizzled them with some kind of liquid. We would call it a night at about 4 a.m., and at five, all the fun started.”

All of The Insider's interviewees refer to Pose as a “very safe space”:

“I was gutted when I heard about the club. I cried all night long. That place was like home because we felt safe there,” recalls Agata, another Pose guest, a bisexual who has been living in Orenburg since 2020 with her husband. Agata says the closure of Pose was a terrible loss for the community.

“If someone was getting handsy, the guards would remove them right away,” Agata explains. “I was once at the club with my friend, and a guy started harassing her. The guards quickly took him outside without any noise. It's not easy to find a place where the safety of guests is taken so seriously. We have another club in the city, and I’ve seen so many times how drunk guys started fighting, sometimes accidentally hitting girls, and it was terrifying.”

Locals who lived next to Pose had no complaints. When we spoke to a group of women in the yard of a nearby apartment block, it took them a while to understand what we were asking about.

“They didn't get in the way. When we went to church on Sunday morning, we would always see them leave the gay club, all drunk… So what? There was never any trouble,” said an elderly lady who was at the playground with her granddaughter.

However, not all locals were quite so tolerant. “Let them go to America and screw each other there! We don't need this kind of thing here, especially since they’ve been banned,” her neighbor chips in.

“They haven’t! Putin said they could do anything, as long as there's no propaganda,” the first woman corrects. The neighbors start to argue, trying to figure out what constitutes “LGBT propaganda” and what status LGBTQ+ people currently have in Russia. Failing to grasp either, they abandon the topic in favor of talking about the beauty salons where they do their hair.

All interviewees have observed increased hostility towards LGBTQ+ people in Russia. However, like the two local women, bullies find it hard to articulate what their problem with the LGBTQ+ community is.

I meet two local girls, Slava and Natalia, at an Orenburg coffee shop. Like my other interviewees, Slava asks me — for safety reasons — not to mention her place of work. Slava is a lesbian and has been to Pose several times. Laughing, she recalls that she once celebrated the New Year there: “We even watched Putin’s address!”

Almost every day, there are customers at Slava's shop who, thanks to the atmosphere created by Kremlin propaganda, see any sort of rainbow as an “LGBT symbol.” Such customers frequently demand that the offending item be removed from display.

“Old folks get offended by rainbow-colored children's pyramids, saying it's [LGBT] propaganda. But pyramids have always been rainbow-colored! They don't even check how many colors there are. Are we supposed to live in a black-and-white world now?” Slava wonders.

The Russian law on “LGBT propaganda” upturned Slava’s life. Before, she “didn’t feel particular hostility” in society towards LGBTQ+ people — including herself — but in 2023 everything changed.

“The government encourages fighting people like me. People are going off the rails. I can feel society getting more aggressive, even in small things. It was as though the law was an order to hate LGBT people and everything about them. It fit the image of an enemy that must be eliminated, and people have become more hostile,” Slava argues. “Footage of raids is being distributed online, there is news of criminal cases against LGBT people, and [propaganda] says people like us should not even exist, that we are an organization created by the West to destroy Russia. Is it the LGBT community's fault that public utilities are not working properly, that entrance halls are dirty, and that pensions are low? Not at all! But it's easier and safer to fight us than thieves and corrupt officials.”

“It’s easier and safer to fight LGBT people than thieves and corrupt officials”

The older generation is the most susceptible to state propaganda and even goes so far as to disown relatives with the “wrong” sexual orientation, even if they did not have a problem with their progeny’s lifestyle earlier, Slava says:

“My girlfriend's mother is advanced in years. She knows about us. She was always understanding about LGBT, joking that people like us had gotten her to support the community in general. Lately, she has taken to talking in toxic cliches from TV broadcasts, saying that LGBT people are depraved and that our sexuality is the result of Western influence. I’ve noticed that others see us as flawed, inferior human beings, not-quite-humans who should not exist at all.”

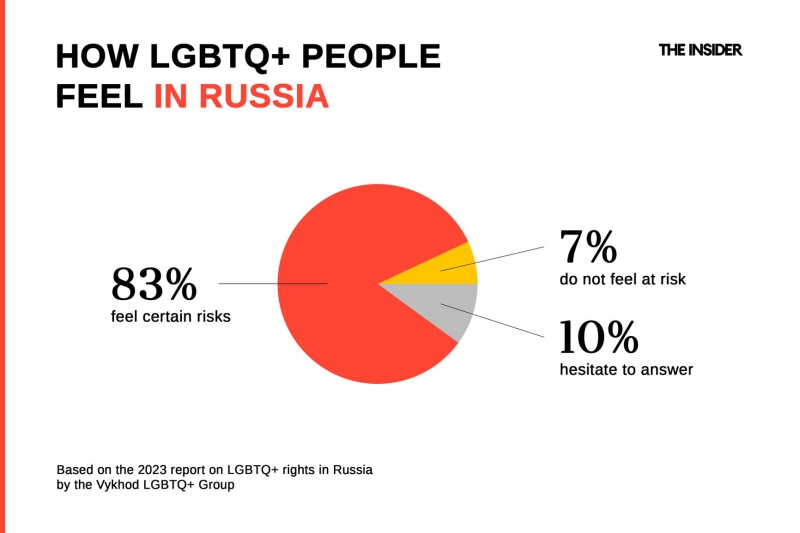

The Volga Federal District, where Orenburg is located, is where LGBTQ+ community members feel the least at ease discussing their sexuality and gender identity. According to a report by the Vykhod LGBTQ+ Rights Group and the Sfera Foundation, in 2023 the share of local respondents who preferred not to come out even to their families reached 44%, surpassing the national average.

“My father says he’d like gay people to undergo ECT in special camps, to be castrated and/or killed,” Sasha says. Her parents have refused to accept her bisexuality. Her friends and family did not consider the raid against Pose or repression against LGBTQ+ people to be a serious problem, and they offered no support.

“They had a laugh, justified and supported what had been done, even gloated. Those who always disliked LGBT people and thought we were fair game openly say they would support the use of violence against us, now that the government's ideology favors it,” another interviewee complains.

Agata has been luckier. Her family was more understanding of her sexuality: “I made sure to choose my words very carefully… I have three younger sisters, and they heard it from me as well. There was no judgment or condemnation. All my family wants is for me to be safe and sound.”

As for coming out to friends in 2023, the share of LGBTQ+ respondents who had been open about their sexuality with most of their friends dropped to only 43% — from 49% a year earlier.

On Sovetskaya Street, which is turned upside down because of road work, a shop selling anime merchandise catches your eye from afar. Three promoters outside the shop are handing out leaflets. The girls are wearing bright wigs, vibrant clothes, and — in the anime style that has found many admirers among teenagers all over the world — even colored contact lenses. Adherents of “traditional values” never had much love for anime fans, but lately their loathing has reached a whole new level.

The “LGBT propaganda” law has unleashed popular hatred towards not only the LGBTQ+ community but also anyone who dares to look unorthodox. Many who use personalized style to express themselves have experienced hostility that has extended even to children and teenagers who dye their hair into vivid colors and wear creative haircuts and piercings.

The “LGBT propaganda” law has unleashed popular hatred towards anyone who dares to look unorthodox

“The manager has given us pepper spray to keep in our pockets,” says Alena, a girl in a green wig. According to her, not a day passes without someone shoving them, giving them a slap upside the head, or making mean comments about their eye-catching looks. Alena says she has seen a surge of hatred towards everything that has to do with anime or K-pop.

“They hate everything too bright — all forms of self-expression. Sometimes, people would just come up and hit me. It's happened a few times,” another promoter says. “Guys attack in groups. They can push you into a corner, and there’s nothing you can do. They can spray you with pepper spray.”

As we are talking outside the shop, a guy in a black hoodie dashes by on a scooter. Approaching, he swerves to the right, as though meaning to push us off our feet. He shouts “Sluts!” And then he rides off. We only just barely have time to jump aside. “See?! That was addressed to us!” Alena says. “And it happens all the time!”

“Kids love us, though! They run towards us, smiles on their faces,” Alena’s colleague Darya interjects. She is the youngest and still goes to school. According to her, school-aged kids have also been facing “a lot of hatred and bullying” because of their looks. She emphasizes that journalists are underplaying the hate teenagers get for trying to look differently. “And if the media mention it, they always present haters and aggressors in a favorable light,” Darya argues.

The guy on the scooter takes off toward Proletarskaya Street, where patriotic posters extolling Russia’s “special military operation” and the “traditional” family cover a long wall some 400 meters from the anime shop. “Glory to Russia,” “We are Russia,” and “Waiting for the Victory” are the titles of what is presented as a series of children's paintings.

People are so brainwashed by propaganda that they see any example of self-expression through fashion as a sign of membership in the LGBTQ+ community, Slava says. “When our shop hired a guy with a nose piercing, my colleagues immediately said, ‘Oh, he must be gay.’ But he is straight — it's just his way of expressing himself!”

Any attempts at self-expression through fashion are perceived as a sign of membership in the LGBTQ+ community

Unsurprisingly, all interviewees have observed a surge in violence against actual LGBTQ+ people. Natalia, Slava's girlfriend, wears a short, bright-colored haircut and piercings. “Slava and I were sitting on a bench in a park, and because of my hair, some guy came up out of the blue and started insulting us: ‘Are you a bloke or a gal? You must be exterminated! You're an abomination!’ and so on. We didn't know how to get rid of him,” Natalia recalls. “Luckily, another guy stood up for us. I don't even feel safe in the park when we're together. But I don't want to change the way I look. I’m comfortable with my appearance.”

Some of Sasha’s acquaintances have been attacked over rainbow-colored earrings or unorthodox looks — and they are not even LGBTQ+.

“Our city has always been a hostile environment, and many LGBT people remained closeted even before such incidents, but the situation has become extreme,” Sasha says. “Many have even stopped wearing earrings for fear of physical violence.”

Since being a member of the LGBTQ+ community can become grounds for criminal prosecution, in 2023 fewer Russian LGBTQ+ people sought help from the police — this despite an increase in violent attacks and cases of hatred-fueled pressure.

Sfera's findings suggest that in 2023, over 43% of respondents survived one or more types of violence because of their sexuality or transgender status. In 2022, the figure was 30%. In addition, one in four respondents faced threats of physical violence last year because of their sexuality or transgender status.

“Many are reluctant to come out because they are afraid it might be a ploy to expose them and take them to a police station for interrogation. People are scared. Especially after the raid on the bar,” Agata says.

“Getting beaten up is bad enough, but it's even worse to end up behind bars or labeled as a foreign agent or extremist simply because they think we love the wrong people,” she explains. “It's easier for me as a bisexual because I can choose between guys and girls, but what are others supposed to do? I have no idea how to help them.”

“This law [on recognizing the 'LGBT movement' as extremist] leads to cases of vigilante justice. If someone is tipped off that a girl is not heterosexual, they can beat her up, knowing that the police will do nothing. The girl won’t even go to the police for fear of getting arrested as an LGBT person, as an extremist,” Agata explains. According to her, sexual orientation — or simply having an unconventional appearance — was always enough to make someone a potential target of violence in Orenburg. Now, however, the LGBT law has equated non-heterosexual people with extremists, providing a pretext for even more aggression.

Russia’s recent LGBT law equated non-heterosexual people with extremists, providing a pretext for even more aggression

“I had an incident in my hometown: a group of guys ambushed me and beat me up, but at least I understood they had no legal grounds to do so,” Agata recalls. Today going to the police has become scarier.

“I’m more afraid of cops and the FSB [Federal Security Service] than of homophobes,” Slava agrees. “In fact, we have no one to protect our rights, our lives. If we get in trouble, they treat us as extremists — unlike the Taliban, whom Russian authorities try to justify!”

“I want to lead a peaceful life and to know that the police will protect me in a conflict, that I can ask them for help. But how are we supposed to go to the police when we’ve been outlawed?” Slava wonders.

LGBTQ+ people are facing particular risks when looking for a partner. The Insider’s interviewees are unanimous: dating has become more complicated and dangerous, as they have to avoid public places even on first dates.

“Coming out is not an option in such an environment,” Agata points out. “It was hard enough even before the law was passed, but at least the bravest of us could dare to be open about their sexuality, especially in big cities.”

Today, simply stating one’s sexuality on a relevant dating site can be enough to bring legal consequences.

“Trusting people has become scarier than ever. Even when I’m at home, I feel like saying the wrong words can land me in jail. I’m terrified,” Sasha confessed. According to her, former Pose customers understood the message of the raid organizers: keep your heads down.

“Some people are abandoning their identities, desires, and dreams. They can’t find a partner, a soulmate, because they are out of ways to do so,” Slava says. “They get tired and sometimes give up trying. Some stay single, and others betray their nature and enter heterosexual marriages, finding solace in children and work. But it has consequences. Some members of our community are opposed to these laws but do not want to fight. They are scared, afraid of losing what they have. They may have children or families.”

The only place where LGBTQ+ Russians can find a partner is chat groups, but people are hesitant to come out because law enforcement agents infiltrate such spaces — with unpredictable consequences. Moreover, despite the repression against them, some members of Russia's LGBTQ+ community are supportive of the government’s other policies. “It’s beyond my comprehension,” Slava says. “A friend of mine said, ‘We’ll push back America and take back Alaska!’ No one is immune to propaganda.”

The only place where LGBTQ+ Russians can find a partner is chat groups, but law enforcement agents infiltrate them as well

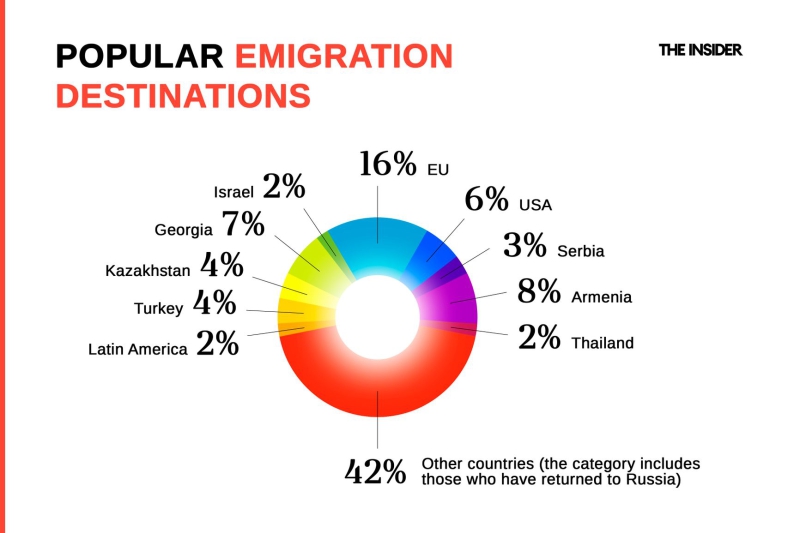

All of The Insider's interviewees agree: the criminal case against “LGBT extremists” in Orenburg is just the beginning. The practice will spread across the country, following the pattern of repression against the free press, political activists, and anti-war Russians. According to the joint report by Vykhod and Sfera, the year 2023 was marked by two distinctive flows of emigration from Russia: after the Kremlin banned gender transition (the period from July to November 2023), and after the “international LGBT movement” was recognized as extremist (November 2023).

“Those who had money have left,” Slava says. “Some left the country and found the love of their life abroad. Others are moving to large cities because dating is easier there.”

However, few in Orenburg can afford to emigrate, as the region ranks 66th in Russia in per capita income and tenth from the bottom of the list in quality of life. This spring, the region's well-being was further undermined by floods. In the city center and outside the city, utility poles, walls, and bus stops are covered in ads offering “work with room and board” and “workhouse” — there are even examples of 90s-era Ponzi schemes promising 50% interest a month.

In the short-term, none of The Insider's interviewees plan to leave Russia, but they are prepared to do so if faced with immediate danger. “We have already been to Kazakhstan and had bank cards issued there, just in case,” Sasha says. All respondents say that they see their future “in a civilized society” that does not restrict their choice of partner.

Only one of Agata’s acquaintances left Russia after the LGBT law was passed. A few more are planning to leave but need to save up first. “Those who don’t have the means to leave stayed in the city and are lying low,” Agata says. “There’s a tiny fraction of those who remain open, living their lives like before because their entourage and the attitude toward them hasn't changed.”

Slava believes some members of the LGBTQ+ community underestimated the threat posed by the recent LGBT law: “When the law was passed, many wrote in our chats that there's no danger and that it won't concern them in any way as long as they don't go about waving the rainbow flag.” They thought it would blow over. Until recently, they believed no clubs would close down and no parties would be banned because ‘there's money in it, and there are our supporters in the government, so it won't be that bad.’ Nevertheless, what this law did was make us all outlaws, leaving no one to protect us.”

“Society has made us realize that expressing our individuality leads to physical and psychological violence. Living under the pressure of disdain is very hard, impossible in the long term,” Sasha believes.

The situation with LGBTQ+ rights in Russia is gradually getting worse, the report says. By late 2023, the Russian LGBTQ+ community had found itself under severe pressure from the authorities and facing intensifying hostility. If the trend continues, next year's outlook will be even grimmer.

“I think it will get worse,” Slava agrees. “Soldiers are coming back from the front, and they are extremely aggressive as it is. Violence against women is on the rise. And the law gives them the green light to attack LGBT people. Television hosts explain to us that Russia is waging a war against NATO, against the West, which they say unleashed the war in the first place, and of course, against LGBT people. If you ask a soldier, ‘What were you fighting against?’ He’ll say: ‘Against people like you!’”