On Nov. 26, the Ukrainian guerrilla movement Atesh sabotaged a rail track in a Russian-occupied area just north of Crimea, disrupting the logistics of the enemy’s armed forces. The act was not an isolated incident: a multi-thousand-strong underground movement, ranging from large organized networks to individual activists, operates in the occupied territories of Ukraine. Their operations go beyond combat missions, with the Yellow Ribbon (“Zhovta Strichka”) partisan association engaging in information warfare along with sabotage efforts. While some guerrillas coordinate their actions with Ukrainian national security agencies, others act on their own — and at their own risk.

Lena (the name has been changed) lives in a small village in the north of the Kyiv Region, a little over a dozen miles from the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone. The Russian units that entered Ukraine from the territory of Belarus on the night of Feb. 24, 2022, captured Lena's village within 24 hours. A Ukrainian territorial defense unit — fifteen or so young men without combat experience, armed only with assault rifles — had arrived in the village from a nearby town, but they could do nothing against the armada of Russian tanks and armored vehicles moving towards Kyiv. And so the fighters buried their uniforms and weapons in vegetable gardens and scattered about the village, seeking shelter in the homes of locals, who later told the occupiers that the young men were relatives.

Lena, still a high school student at the time, knocked on doors, asking neighbors to hide territorial defense fighters in their yards. According to her, no one said no — not even those who later cooperated with the occupiers handed over the Ukrainian fighters to the Russians.

Lena's boyfriend joined the army in the early days of the full-scale war. She managed to contact him on his cell phone and said she wanted to help the Armed Forces of Ukraine in any way she could. A little later, Lena received a message with instructions: her job was to find out the addresses where Russian officers were stationed and where they had parked their vehicles. She was to delete all messages, both incoming and outgoing, immediately after reading or sending them.

The young woman did not arouse the suspicions of the invaders. She walked the streets of her native village, found the houses where Russian commanders were staying, and passed the information along to Ukraine's defenders. Based on her tips, the AFU destroyed a house that accommodated several officers and a warehouse with artillery shells, along with a truck that carried these shells to Russian firing positions. She also helped the territorial defense fighters escape the occupied territory and join the defense forces fighting for the Kyiv Region.

The young woman did not arouse the suspicions of the invaders and soon found the houses where Russian commanders were staying

Lena acted alone — she was not an intelligence officer or a soldier. She became part of the resistance not by order, but by her own free will. She made a list of rules for herself, which she never broke and which kept her alive and safe under the Russian occupation:

“I never ingratiated myself with the Russians. I could even argue with them, and I never asked for any favors. They expected locals to bow down to them, and my attitude left them confused. I only used a push-button phone because they searched for spotters with smartphones, which could transmit more or less precise GPS coordinates. I never told anyone what I was doing, not even my parents. I always prepared plausible explanations for what I was doing on this or that street, at this or that house, in case Russians asked me about it.”

When the Kyiv Region was liberated in early April 2022 and Lena's one-woman resistance came to an end, a whole underground network operating in the south and east of Ukraine first announced itself.

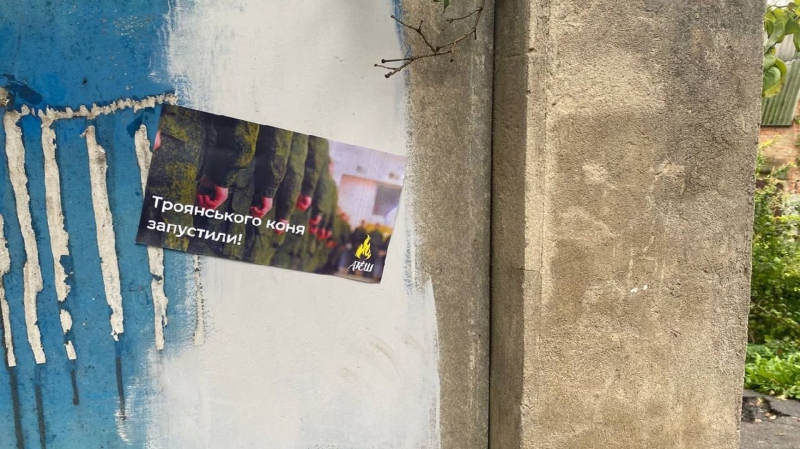

In occupied Kherson, unknown individuals started tying yellow ribbons to poles and trees. Graffiti depicting such ribbons began to appear on the walls of buildings, including those that housed the occupiers' authorities. The ribbon became a symbol of resistance against the invasion and inspired the name of an entire movement.

Yellow Ribbon (“Zhovta Strichka”) began as an underground association of Kherson residents who wanted to fight the occupation. Soon the movement obtained another recognizable emblem: the letter Ї, present in the Ukrainian Cyrillic alphabet but not the Russian. Images of this letter also began to appear in the occupied territories as a symbol of resistance to the invaders. These seemingly simple symbols have powerful propaganda potential. Yellow ribbons and graffiti signal to Ukrainians opposed to the occupation that they are not alone — and to the occupiers that they are not welcome.

In addition, insurgents evacuate people from areas of intense hostilities, publish a newspaper that is distributed in the captured territories, and urge locals not to make concessions to the invaders — whether by participating in “elections” and “referendums” or by taking a Russian passport. Yellow Ribbon representatives deny having any affiliation with any of Ukraine's security agencies.

Their fellow guerrilla fighters from the Atesh movement are mainly active in Crimea (“atesh” means “fire” in Crimean Tatar) but also operate in other regions — and even in Russia. Atesh members say that the movement has Russian career officers among its guerrillas and informants, allowing Ukrainian security services to receive information directly from the enemy's military units, warships, and training bases.

The movement claims that they have no formal ties to Ukrainian governmental agencies but that they work in close coordination with officers responsible for the occupied territories. The link is likely very tight indeed, The Insider's sources say.

Kyiv openly admits that a vast network of Ukrainian security agents operate in Crimea and other occupied regions of Ukraine. The backbone of the network is made up of professional scouts and saboteurs, whose missions include setting up ambushes against the occupiers, the targeted elimination of war criminals, and other high-profile operations. It is unlikely that the guerrillas carrying out these actions, which have included spotting for Ukraine’s missile strike on the headquarters of the Russian Black Sea Fleet in Crimea, prepared for them without the assistance or even direct involvement of professionals.

Atesh and lesser-known underground networks normally take orders and receive support from the National Resistance Center — a unit of the AFU Special Operations Forces responsible for countering Russia’s presence in the occupied territories.

Underground networks normally take orders and receive support from the AFU's National Resistance Center

The Center has an online portal where one can submit a report about the actions of the occupiers, find a Molotov cocktail manual, and even download software tools useful in covert operations.

As an entity within the Special Operations Forces, the National Resistance Center keeps a tight lid on its activities. The Center does not disclose information about its future or past operations, does not hold public events, and prohibits its employees from giving comments to the media. However, the available information makes it possible to form a detailed picture of guerrilla activities in the occupied territories. The center's competence includes not only information warfare and reconnaissance, but also combat missions.

After the Russians seized part of the Kherson Region, several dozen Ukrainian soldiers volunteered to stay in the occupied areas. They were tasked with coordinating fire on the occupying troops and staging sabotage attacks. Most of these saboteurs had been civilians who joined the armed forces and took up arms only after the full-scale invasion began.

The hasty retreat of the core AFU forces from several districts of the Kherson Region in the first week of the war did not leave them time to train saboteurs for long and dangerous work behind enemy lines. They had no fake IDs, no reliable means of communication, and no food supplies. As a fighter with the call sign “First” recalls, those who stayed in the Kherson Region could count only on themselves and the help of locals.

“My son's classmate, whom I knew to be pro-Ukrainian, helped me with communication. He installed a secure messenger on my phone and deleted all Russian apps. Just in case, I kept this phone at an acquaintance's cottage outside the city. I dropped by once every few days, turned it on, checked messages from commanders, and answered them. Then I turned it off and hid it,” the fighter recalls.

At first, his only task was to provide information on where the bulk of the Russian forces were stationed. This was necessary in order to coordinate Ukrainian missile and artillery strikes. As time went on, his tasks became more complex, with First and his fellow partisans being ordered to destroy enemy personnel and vehicles whenever possible.

The fighters began attacking Russian patrols and remote checkpoints. They usually operated at night and conducted thorough surveillance to see if there were any enemy reinforcements nearby. They made extensive use of Molotov cocktails, setting fire to warehouses and parked vehicles — including armored vehicles. A few bottles were enough to burn up a KAMAZ truck or even an armored personnel carrier.

A few Molotov cocktails were enough to burn up a KAMAZ truck or even an armored personnel carrier

The guerrillas also verified the outcomes of strikes against Russian targets — strikes that had been conducted based on intelligence they had provided to the Ukrainian military. It was not always possible to do this directly at the point of impact. In some cases, all they could do was observe the hospitals where the wounded enemy soldiers were brought and judge the success of the mission based on the number of visible casualties.

As First recalls, both his group and several other crews operating in the vicinity decided to withdraw in the summer of 2022, when the Russians began hunting saboteurs down. Through a network of agents that had taken shape by then, the underground fighters obtained papers that they could use to make their way into Kyiv-controlled territory.

First believes that he could have stayed underground longer, but his group’s successes in the first weeks of the occupation placed him and his comrades very high on the invaders' wanted list. He presumes that today, Ukrainian agents in occupied territories are acting less rashly and perhaps rotate regularly in order to make it harder for the Russians to detect spotters and saboteurs.

At the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukrainians already had extensive experience operating an underground resistance — the first partisans and guerrilla cells appeared all the way back in 2014, when Russia started its war against Ukraine by illegally occupying Crimea and fomenting an eight-year-long armed conflict in Donbas. Since then, the ranks of the resistance have bloomed, with many of its fighters eventually graduating from underground work into direct military service. The most famous Ukrainian partisan of this war, Artem Karyakin, who as a schoolboy found himself under occupation and voluntarily began waging a personal war against the Russians, has since left the underground in favor of open confrontation with the enemy.