The rivalry between Saudi Arabia and the UAE entered a particularly heated phase in late December when Riyadh’s forces struck a shipment to a Yemeni port under Abu Dhabi’s control. A new war in the Gulf did not break out this time, but the conflict between the two monarchies is just one in a long line of areas of competition among the region’s main players, who are competing for territory, resources, and the favor of Donald Trump.

On Dec. 30, Saudi aircraft attacked the port of Mukalla in southern Yemen. According to Riyadh, the target was weapons and vehicles supplied from the UAE to the Southern Transitional Council (STC), a UAE-backed group advocating for the independence of southern Yemen. Saudi Arabia justified its actions by claiming that the UAE and its protégés in southern Yemen posed a threat to its national security.

What caused the rift between the former allies? Back in 2015, the two influential Gulf monarchies formed a coalition to fight Ansar Allah, the pro-Iranian Houthi rebels who had seized control of part of Yemen. However, after the formal withdrawal of the coalition forces in 2019, the UAE began turning key Yemeni ports under its de facto control into military bases. It also continued to sponsor the Southern Transitional Council (STC) — led by former Aden governor Aidarus al-Zoubaidi — along with other armed groups. That put them on the opposite side of Saudi Arabia, which in 2022 began supporting the Presidential Leadership Council headed by Rashad al-Alimi.

An ambitious national transformation program in Saudi Arabia, launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The Abraham Accords are a series of agreements normalizing relations between Israel and several Arab states, signed in 2020–2021 at the initiative of Donald Trump.

The latest conflict was triggered by the UAE’s attempt to boost its influence in the region using the STC. In recent years, the UAE’s allies in Yemen had repeatedly tried to assert control over Aden, the capital of the anti-Houthi south of the country.

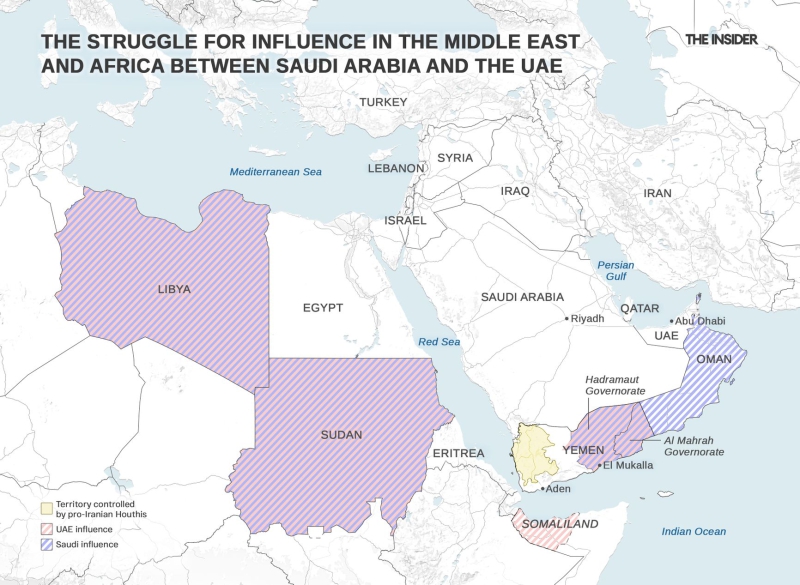

An STC offensive in December 2025 came close to achieving that goal. Quickly seizing control over most of the eastern governorates of Hadramaut and Al-Mahrah, the UAE-backed “Southerners” announced that after a two-year transitional period they plan to declare an independent state of “South Arabia,” with its capital in Aden. In response, the Saudi-allied Presidential Leadership Council requested urgent assistance from Riyadh.

An ambitious national transformation program in Saudi Arabia, launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The Abraham Accords are a series of agreements normalizing relations between Israel and several Arab states, signed in 2020–2021 at the initiative of Donald Trump.

The first of the governorates captured by the STC in December, Hadramaut, shares a 700-kilometer border with Saudi Arabia. Through Al-Mahrah, Riyadh could gain direct access to the Indian Ocean, where it has long planned to build a pipeline connecting its Eastern Province to the coast. This pipeline would reduce the kingdom’s logistical dependence on the Strait of Hormuz, whose shipping could easily be disrupted by Shiite Iran, a longstanding adversary of the ruling Wahhabi dynasty.

It is hardly surprising that after the STC refused to comply with Saudi Arabia’s demands to withdraw its forces (and closed Aden airport when Riyadh tried to send negotiators), the Saudi air force struck the port of Mukalla. The show of force worked. Abu Dhabi preferred not to escalate the situation into a direct confrontation with an influential ally and instead announced the complete withdrawal of its forces from Yemen.

The UAE’s defeat was not total. Although allies of the Saudis regained control over the lost provinces and entered the central districts of Aden, and although some STC members were taken to the Saudi capital, where they announced the dissolution of the organization, their leader Aidarus al-Zoubaidi was notably absent. According to the Saudis, he fled by boat to Mogadishu. In reality, however, the STC leader escaped to Abu Dhabi with the help of Emirati forces.

In short, it appears that the UAE’s game is far from over. They still have remnants of the STC that are partially loyal to them, and armed groups like the National Resistance Forces, which are currently coordinating their actions with the Saudi-aligned Presidential Council, could switch sponsors.

Despite its recent successes, Saudi Arabia still faces quite a challenge in Yemen. First, it must unite all the southern forces. Then it must attempt the even more difficult task of negotiating with the Houthis. And one should not forget about Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), which could easily regroup to take on its former adversaries — mainly UAE-allied groups.

In reality, the STC offensive in Yemen represents just a fraction of the complex rivalry among the Gulf monarchies — which extends to competition for the attention of Washington. The Yemeni crisis coincided with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s visit to the White House, where he and Donald Trump discussed, among other things, a no less complicated situation: the civil war in Sudan. The country of a little over 50 million people is now embroiled in a full-scale humanitarian catastrophe that began in April 2023 following a conflict between the chairman of the Sovereign Council (the interim governing body), army commander Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the head of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo.

The clashes that began in Khartoum quickly spread to other parts of the country, with the UN estimating that 14 million people have been forced to leave their homes. Of these, 9.3 million are internally displaced, and over 4.3 million have fled the country. The death toll, according to various sources, ranges from 40,000 to 250,000, and 21 million Sudanese are facing acute food shortages.

An ambitious national transformation program in Saudi Arabia, launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The Abraham Accords are a series of agreements normalizing relations between Israel and several Arab states, signed in 2020–2021 at the initiative of Donald Trump.

The UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the U.S. make up the “quartet” of mediators tasked with coordinating efforts to end the conflict in Sudan. However, the mechanism established in September is barely functional due to lingering tensions between the Emirates and Saudi Arabia. Both Sudan’s Sovereign Council (under al-Burhan) and Saudi Arabia accuse the UAE of supporting the RSF. It is therefore unsurprising that unconfirmed rumors have circulated that Mohammed bin Salman asked Trump to designate the RSF as a terrorist organization and to impose sanctions on the UAE.

The second notable event in the region involves Israel’s recognition of Somaliland’s independence this past December, a move that few doubt was made in coordination with the UAE. The Emirates actively cooperate with Somalia's self-declared territory and, according to some reports, are developing a military base at the port of Berbera. Incidentally, the fugitive head of Yemen’s STC had a transfer at this very port on his route from Aden to Abu Dhabi.

Most Arab countries condemned Israel’s decision, but not the UAE. Over the past decade, the Emirates have sought to expand their sphere of influence all the way from Libya to the Horn of Africa. The signing of the Abraham Accords, followed by deals in security and technology, helped advance this goal.

Despite their differences when it comes to selecting clients, the approaches taken by Saudi Arabia and the UAE share one notable similarity: both are willing to support the emergence of friendly regimes as long as the new powers allow them to control access to the Red Sea and the Arabian Sea. “In this respect, while retreating from Yemen is no doubt a setback, it does not change the UAE’s overall strategy — unless there is a change of heart or of leadership at home,” says Nabeel Khouri, an expert at the Arab Center in Washington, DC. At the same time, Khouri notes, Saudi Arabia views this development as a threat to its own trade and freedom of navigation.

An ambitious national transformation program in Saudi Arabia, launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The Abraham Accords are a series of agreements normalizing relations between Israel and several Arab states, signed in 2020–2021 at the initiative of Donald Trump.

While retreating from Yemen is no doubt a setback, it does not change the UAE’s overall strategy

These concerns may also be shared by other regional players, like Egypt, Iran, and Turkey. Moreover, unlike Abu Dhabi, Riyadh prefers to build relations with official authorities rather than with separatist groups. In this regard, the Emirates are less selective. Overall, however, the issue is mainly about the struggle for influence.

Even before becoming crown prince in 2017, Mohammed bin Salman chose as his political role model Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, president of the UAE. Having matured into the de facto ruler of his kingdom, the prince has decided that Saudi Arabia must reclaim its role as the region’s leader, and the atmosphere between the two charismatic leaders has grown tense as a result.

In July 2021, the UAE blocked a package of agreements within OPEC+ demanding a revision of the baseline oil production level, which Abu Dhabi deemed unfair given its growing capacities. The Emirates also opposed Saudi Arabia’s requirement that foreign companies operating in the kingdom relocate their regional headquarters to Riyadh by 2024 (most of them were based in Dubai). The companies were threatened with the loss of Saudi government contracts if they did not comply. This was accompanied by the removal of tariff benefits on goods from the UAE’s free economic zones, which was aimed at undermining the trade model of Dubai, the most successful emirate in this sector.

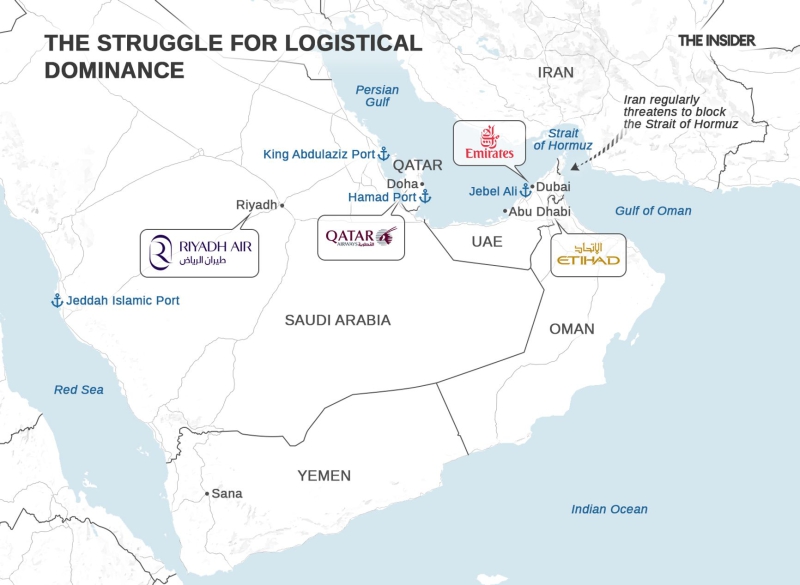

Another line of competition which has become especially noticeable in light of the developments in Yemen is logistics, in the form of ports and civil aviation. Here, in the struggle over the title of the main “transit hub” between Europe, Asia, and Africa, there are several competitors. The UAE banks on the combination of the Emirates airline in Dubai and Etihad in Abu Dhabi, while Qatar has Qatar Airways in Doha.

An ambitious national transformation program in Saudi Arabia, launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The Abraham Accords are a series of agreements normalizing relations between Israel and several Arab states, signed in 2020–2021 at the initiative of Donald Trump.

As part of Vision 2030, Saudi Arabia seeks to capture a share of transit traffic by creating Riyadh Air and developing airport infrastructure in Riyadh. At sea, the UAE relies on Jebel Ali Port and the global operator DP World. Saudi Arabia focuses on its Red Sea and Persian Gulf port system, including Jeddah Islamic Port and King Abdulaziz Port in Dammam. And Qatar relies on Hamad Port, built and expanded after the 2017 crisis, when neighboring countries collectively imposed a blockade on Doha.

An ambitious national transformation program in Saudi Arabia, launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The Abraham Accords are a series of agreements normalizing relations between Israel and several Arab states, signed in 2020–2021 at the initiative of Donald Trump.

Among the areas of likely future competition are AI development and applications. The Arabian monarchies — primarily Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar — are betting on AI as a potential replacement for oil and gas as a source of economic growth and regime stability. Saudi Arabia has established HUMAIN, a company that reports directly to the crown prince and is intended to replicate the model of the state oil company Saudi Aramco — only in the realm of data and computing power. Meanwhile, the UAE became the world's first country to create a Ministry of Artificial Intelligence, and it is investing in the large-scale Stargate computing center, which is scheduled to launch in 2026.

The Saudi prince’s American visit is just one example of the competition among Arabian monarchies for the opportunity to lobby their interests in Washington. In practice, this rivalry primarily takes the form of economic diplomacy.

It is enough to recall the investments in the U.S. economy promised by the monarchies during Trump’s visit to the Gulf region last May. Saudi Arabia pledged $600 billion, and upped the contribution to $1 trillion by the prince’s November trip. The UAE, meanwhile, announced deals worth $1.4 trillion, plus additional investments. Qatar put forward a figure of $1.2 trillion, which included the royal plane gifted to Trump.

An ambitious national transformation program in Saudi Arabia, launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The Abraham Accords are a series of agreements normalizing relations between Israel and several Arab states, signed in 2020–2021 at the initiative of Donald Trump.

In the meantime, another race for influence is unfolding in Washington. The Gulf countries maintain permanent networks of lobbyists and PR contractors in the U.S. capital, investing in access to decision-making through events, contacts, and media presence. They are also expanding their soft power through research centers and university programs.

Qatar's efforts are of particular note. Since Trump’s first term as president began in 2017, Doha has spent nearly $250 million on 88 lobbying and PR firms registered under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA). The effort continued under Biden with Qatari agents reporting 627 in-person meetings with political contacts in the U.S between January 2021 and June 2025.

Other monarchies are also active in this field. In 2020–2021, 25 organizations representing UAE clients were registered in the U.S., reporting 10,765 contacts. Additionally, according to data compiled by the Jewish Virtual Library, from 1981 to 2024 American universities received more than $14.6 billion in contributions from Arab governments and institutions. Here, Qatar also leads with $6.6 billion, followed by Saudi Arabia at $3.9 billion and the UAE giving $1.7 billion. Moreover, many American universities have branches in the Gulf countries, another line of investment.

An ambitious national transformation program in Saudi Arabia, launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The Abraham Accords are a series of agreements normalizing relations between Israel and several Arab states, signed in 2020–2021 at the initiative of Donald Trump.

From 1981 to 2024 American universities received more than $14.6 billion in contributions from Arab governments and institutions

Other countries around the world are also becoming fields for lobbying, and the Arab monarchies are competing for the role of mediator in resolving global conflicts. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine marked the first time these players moved beyond the Asia–Middle East–Africa arena. Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE all took part in negotiations on prisoner exchanges and other humanitarian issues, with Riyadh even hosting talks between American and Russian delegations.

Another noteworthy aspect involves the media competition between the three monarchies — not only for regional, but also for global influence. Doha was among the first to invest in this tool, and since its launch in 1996, the Al Jazeera network has gained influence not only in Arab countries, but far beyond the Middle East. Al Jazeera English was launched in 2006, while Saudi Arabia’s Al Arabiya launched its English service in 2007. During the blockade of Qatar that was imposed in 2017 by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt, one of the demands made on Doha was the closure of Al Jazeera.

An ambitious national transformation program in Saudi Arabia, launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The Abraham Accords are a series of agreements normalizing relations between Israel and several Arab states, signed in 2020–2021 at the initiative of Donald Trump.

Now the Gulf monarchies are moving beyond mere networks to actively build their own media empires. In 2020, Saudi Research and Media Group (SRMG) launched the multi-platform news project Asharq News, and in 2019 added Independent Arabia under a licensing agreement with The Independent brand. Separately, SRMG develops the business brand Asharq Business under an agreement with Bloomberg Media. The holding also owns one of the region’s most influential newspapers, Asharq Al-Awsat, which has editions in English, Farsi, and Turkish. The UAE is developing its own media outlets: Sky News Arabia (a joint venture with Sky that is based in Abu Dhabi) and English-language media such as The National.

Throughout his first term, Trump sought to build an anti-Iranian axis linking Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Israel. It was in this context that the Abraham Accords were conceived. In 2020, the UAE and Bahrain were the only two Gulf monarchies to sign them, despite Trump’s hopes to persuade Saudi Arabia to join as well. This was no longer just a political alliance, but a global economic cooperation project connecting Europe, the Middle East, and India — all of it in the interests of the U.S. and in opposition to China.

In the fall of 2023 Saudi Arabia came close to joining the Abraham Accords, inspiring hope for an official normalization of Saudi–Israeli relations within months, if not days. But the situation shifted after the Hamas terrorist attack on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, which led to war in the Gaza Strip and subsequently in Lebanon. One of Hamas’s possible objectives for the massacre may have been to disrupt Riyadh’s accession to the Abraham Accords (in which case it worked).

Meanwhile, the UAE actually strengthened its ties with Israel amid the war in Gaza. Unlike Saudi Arabia — home to the two holiest sites in Islam — Abu Dhabi has no obligations to the Islamic world. As a result, a new “Israel – UAE” axis has emerged in the region, one actively operating across a broad geographic area between the Middle East and Africa.

Meanwhile, the region’s “anti-Iran” alliance has effectively disappeared. Even before the Gaza war, Riyadh and Tehran had announced the normalization of relations and restored diplomatic contacts. While it is premature to speak of a fully rebuilt trust, Saudi Arabia has chosen a frigid peace over war, and the kingdom has no objections to the imposition of economic pressure on Iran from the U.S. and the EU, nor to outside efforts to weaken Tehran’s regional proxies. However, a large-scale war in the region is not in the interest of any Gulf monarchies, which is why most countries — the UAE excepted — actively discouraged Trump from striking Iran amid the latest wave of mass protests.

An ambitious national transformation program in Saudi Arabia, launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The Abraham Accords are a series of agreements normalizing relations between Israel and several Arab states, signed in 2020–2021 at the initiative of Donald Trump.

The alliance of Arab monarchies against Iran has collapsed

Saudi Arabia has also moved closer to Oman, which had previously maintained a deliberately neutral stance, and to Qatar, against which Riyadh and Abu Dhabi had presented a united front back in 2017, severing relations with Doha and imposing an economic boycott.

In addition, the Saudi kingdom has formalized its long-standing defense sector cooperation with Pakistan. In September 2025, Riyadh and Islamabad signed a mutual defense agreement under which an attack on one party is considered an attack on both. Turkey now seeks to join this alliance, motivated by doubts about the reliability of U.S. assistance in the event of military conflict. Nevertheless, the Gulf countries have not abandoned their partnership with the U.S. in this area. In November, during Mohammed bin Salman’s visit to Washington, it was announced that the kingdom would be included among America’s major non-NATO allies. Qatar has been on this list since 2022, and the UAE has held major security partner status with the U.S. since 2024.

The concept of a “Middle Eastern NATO” is a recurrent theme for Arab countries, including the Gulf monarchies, but persistent disagreements have so far prevented its development. As a result, each is now focusing more on frameworks that extend beyond the region. At the same time, the idea of establishing a unified regional air defense/missile defense system has been under discussion and gained new momentum following Israeli strikes on Qatar. Such a system would encompass radars, data sharing, and joint interceptions to protect the Gulf states — and ideally, it would involve coordination with the U.S.

Nevertheless, stable regional alliances are out of the question. As the situations with Qatar and Iran have shown, priorities and alliances in the region are highly volatile. The only thing that unites the Gulf rulers is that none of them wants chaos on their doorstep.

An ambitious national transformation program in Saudi Arabia, launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The Abraham Accords are a series of agreements normalizing relations between Israel and several Arab states, signed in 2020–2021 at the initiative of Donald Trump.

The only thing that unites the Gulf rulers is that none of them wants chaos on their doorstep

Saudi Arabia’s rapprochement with Turkey and Pakistan, as well as the warming of its relations with Qatar, is raising concerns in Israel, which now fears facing a “Sunni axis” instead of an “Iran-led Shia axis.” However, the threat from Iran is far from resolved, meaning contacts with the UAE and its regional partners are critically important for Israel (even if none of them are very reliable).

However, as long as the rivalry between the UAE and Saudi Arabia continues, Israel need not worry. A war between Abu Dhabi and Riyadh is not likely, and experts do not foresee a boycott like the one imposed on Qatar. Trade cooperation between the countries remains active, and no one will forgo their own benefits, even as they continue playing against each other in various arenas.

An example of such an area is Libya, another divided country with no stable central authority where shifts in coalitions among external players supporting various local groups are also evident. Previously, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Egypt sided with the Libyan National Army (LNA) led by Khalifa Haftar, which controls eastern Libya. Qatar and Turkey supported the Government of National Unity (GNU) in Tripoli. But in early January, Arab media reported that Cairo and Riyadh are moving closer to the GNU due to Haftar’s support for the Sudanese RSF.

Egypt and Saudi Arabia are also more flexible regarding Palestinian issues and cooperation with Hamas in Gaza — although unlike Qatar and Turkey, they have not been close to the group. The UAE’s stance toward Hamas is as uncompromising as Israel’s, but will Israel receive enough support on Gaza-related matters from the UAE alone, given that Trump is influenced by those who are most useful to him at the moment? In this regard, the competition between Riyadh and Abu Dhabi — including over influence in the White House — could lead to unpredictable consequences for Israel.

An ambitious national transformation program in Saudi Arabia, launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The Abraham Accords are a series of agreements normalizing relations between Israel and several Arab states, signed in 2020–2021 at the initiative of Donald Trump.

This rivalry also creates problems for the U.S., as Trump is reluctant to take sides when it comes to allies. He needs them all, along with their money and assurances that they will not expand their ties with China — which, however, is already happening.

The European Union is also concerned about the Saudi–UAE confrontation, fearing it could harm the interests of European countries that cooperate with both sides.

The situation is no less difficult for the Kremlin, which has been actively developing ties with all the Gulf countries (with the UAE and Saudi Arabia as its main allies). In addition, Russia has its own military interests in Libya, Sudan, and other African countries.

However, over the years of the Saudi and UAE boycott of Qatar, many external players learned to maneuver between the rival sides without doing damage to their own interests. For the time being, the decisive factor is the renewed tensions between Washington and Tehran, which complicate forecasting in a region marked by traditionally unstable coalitions between monarchs who are still competing for territory, resources, and Washington’s favor.

An ambitious national transformation program in Saudi Arabia, launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

The Abraham Accords are a series of agreements normalizing relations between Israel and several Arab states, signed in 2020–2021 at the initiative of Donald Trump.