Before visiting the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea — the Northern one, also known as the DPRK — Vladimir Putin continued his recent series of “historical lectures.” An article published under the Russian president’s byline in the state-owned North Korean newspaper Rodong Sinmun (and in its Vietnamese equivalent, Nhan Dan) argued that Vietnam and North Korea have been Moscow’s longtime friends and allies, and that it makes sense for the relationship to continue. An excerpt from the article, published in Russian on the Kremlin’s website, reads:

“In the challenging time of the Fatherland Liberation War of 1950-1953, the Soviet Union also extended a helping hand to the people of the DPRK and supported them in their struggle for independence. Subsequently, the USSR provided significant assistance in the restoration and strengthening of the young Korean state’s economy and in the establishment of peaceful life.

“…Russia has always supported and will continue to support the DPRK and the heroic Korean people in their confrontation with an insidious, dangerous, and aggressive enemy, in their struggle for independence, identity, and the right to choose their own path of development.”

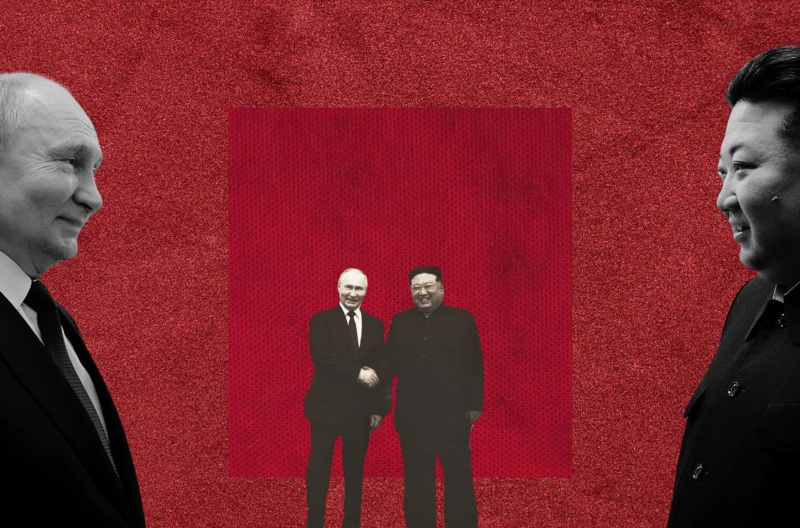

The main outcome of Putin's Pyongyang visit was the unveiling of a Treaty on the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between the two increasingly rogue states. In confirmation of South Korean and Japanese officials’ worst fears, the document includes a commitment by Russia and the DPRK to support each other with all their strength in the event of an attack against either side. The new treaty marks a new, fourth stage in Moscow-Pyongyang relations. For a deeper understanding of this development, we should heed Vladimir Putin’s advice and turn to the history of this relationship (albeit to the factually accurate one). In reality, the “friendship” between the two capitals was rife with cynicism and conflict, as North Korean diplomats artfully maneuvered to exploit any rifts between the USSR and China to their own geopolitical advantage.

Stage 1: Soviet control of the DPRK (1945-1957)

North Korea came into existence largely by accident. The day the American atom bomb was dropped on Nagasaki — Aug. 9, 1945 — the Red Army launched its invasion of Manchuria, Imperial Japan’s largest colonial holding. As a result of this campaign, Soviet forces took control of the northern part of the Korean Peninsula. The American leadership, realizing that the entirety of Korea could soon fall under Moscow's control, proposed to Stalin that the peninsula be divided along the 38th parallel, roughly in half. Stalin agreed, leaving Seoul, which sits just below the line of demarcation, in the American zone.

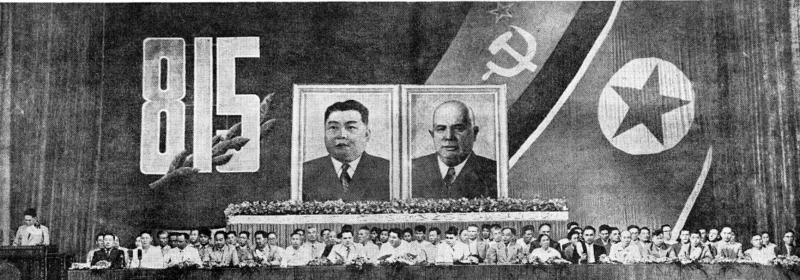

At first, the nascent North Korean state was under Moscow’s total domination. Early on, the leadership in Pyongyang answered to Ivan Chistyakov, the commander of the Soviet 25th Army. Later, authority was exercised by Terenty Shtykov, the head of the Soviet delegation to the Soviet-American Commission on Korea and the first Soviet ambassador to the DPRK.

At first, the nascent North Korean state was under Moscow’s total domination

The Soviet control was not official, with laws drafted by the Soviet administration presented to the nation as “decrees of the people's government and Commander Kim Il Sung,” who until 1945 had served as a battalion commander stationed in the rear of the Soviet Red Army.

Kim Il Sung regularly expressed his “eternal gratitude” to the Soviet Union for “liberating Korea from the Japanese yoke.” In 1947, the Liberation Monument in Pyongyang was erected in honor of the Red Army soldiers who participated in the operation, and many more symbols of official gratitude to Soviet soldiers could be seen throughout the country.

Despite his superficial show of gratitude and loyalty, Kim Il Sung had an agenda very different from Moscow’s: he sought to become an independent ruler. Achieving this goal took the Korean leader a decade and a half, but he ultimately got what he wanted.

Soviet control over the DPRK began to wane in 1950, when Pyongyang obtained operational autonomy by unleashing the Korean War. The fighting continued into the mid-1950s, and after Stalin’s death in 1953, Kim Il Sung successfully purged the Communist Party’s Central Committee of disloyal members. He held onto power despite the wave of de-Stalinization triggered by Khrushchev's February 1956 “secret speech” denouncing the cult of personality surrounding the deceased despot.

The final stage in the DPRK dictator’s struggle for de facto independence came in September 1957, when Kim Il Sung ignored Moscow's instruction to establish a system of collective leadership and to appoint someone else as Chair of the Council of Ministers. When the Soviet leadership failed to enforce the demand, Kim Il Sung realized he could finally do whatever he pleased.

Stage 2: A schism between China and the Soviets, and a struggle over history (1957-1990)

Shortly after Kim Il Sung wrenched himself free from Soviet control, Moscow had a falling out with Beijing. Mao Zedong did not approve of de-Stalinization or the Soviet course for peaceful coexistence with the West. Relations between the Soviet Union and China became openly hostile as Beijing castigated the “Brezhnev-Kosygin gang,” comparing the Soviet leader to Adolf Hitler. Moscow responded with a barrage of criticism directed at Maoism and the Chinese Red Guards.

The confrontation was largely ideological, but Kim Il Sung, ever a cynical despot, always placed his benefit and power above any ideology. He saw the Soviet-Chinese quarrel as an opening and designed North Korean policy to take advantage of the opportunity it presented.

Pyongyang was deliberately vague and inconsistent in stating its position. In 1962-1965 and 1970-1982, its sympathies leaned toward Beijing, but in 1982-1987, Pyongyang favored the Soviet Union. Yet Kim never showed full solidarity with either Moscow or Beijing in any of these periods, forcing both superpowers to make concessions in the hope of “pulling” the DPRK to their side.

Kim Il Sung never showed full solidarity with either Moscow or Beijing, forcing both superpowers to make concessions

One such case involved treaties of “friendship, co-operation, and mutual assistance.” North Korea signed just such a document with the USSR on Jul. 5, 1961 — one that also involved the pledge of mutual security guarantees. But before Moscow could properly celebrate the success, on Jul. 11 North Korea signed a nearly identical treaty with China.

In addition to receiving economic and security benefits, this duality also helped Kim Il Sung in a no less important aspect of his policy: falsifying history. The North Korean dictator did not take part in the Soviet-Japanese War, spending that time at a military base near the village of Vyatskoye in Khabarovsk Krai in the Soviet rear. However, the leader’s inflated ego gave birth to a new version of those events, one in which the main role in the defeat of Japan belonged to Kim Il Sung's so-called “Korean People's Revolutionary Army” — an entity that had quite simply never existed. Kim Il Sung was also said to have been fighting in the Revolutionary Army in his youth, while in reality he fought in Manchuria alongside Chinese Communists, and not the “independent” Korean army.

Kim Il Sung attributed the victory over Japan to the entirely fictitious “Korean People's Revolutionary Army”

Kim’s rewriting of history reached its peak in 1967, when North Korea began to actively demolish monuments to Soviet soldiers, replacing them with monuments to Korean Revolutionary Army fighters. “The dismantling and relocation of monuments were carried out unceremoniously. They were literally destroyed, broken for the local population to see,” Soviet diplomats in the country wrote. Manifestations of “eternal gratitude to the Soviet liberators” became a thing of the past the moment they stopped bringing political benefit.

Kim Il Sung's behavior also caused consternation among former Chinese comrades in the guerrilla struggle, who did not expect the dictator in Pyongyang to dissociate himself from them so easily. But Kim Il Sung understood perfectly well that the Soviet KGB and Chinese Bureau of Investigations of the Communist Party's Central Committee would not allow direct criticism of the North Korean narrative, as such negativity could compel North Korea to side with the enemy.

Kim's gamble paid off — to a point. As a form of indirect response to Pyongyang’s recalcitrance, Moscow published a collection of official memoirs of the combatants in the Soviet-Japanese war, along with the almanac “Relations between the Soviet Union and the People's Korea” (1981), which included several actual historical war documents. Pyongyang appeared unperturbed, staging ever more festivities to commemorate the “liberation of the homeland by the Korean People’s Revolutionary Army.” One of the main highlights was the unveiling of the Arch of Triumph in Pyongyang — probably the world's largest memorial to a blatantly fictitious event.

Stage 3: No trade and talk of friendship (1990-2023)

The third stage in Soviet-North Korean relations began in 1990, when Moscow extended South Korea official diplomatic recognition and curtailed economic aid to Pyongyang. Later, independent Russia restored good relations with North Korea but officially annulled the 1961 treaty of cooperation. Initially, the DPRK perceived the rejection of the 1961 document and the recognition of its southern neighbor as acts of betrayal, but a few years later, Pyongyang had to accept that Moscow would not close its embassy in Seoul. With time, the DPRK itself began to establish relations with the “military-fascist puppet regime” in Seoul — the neighbors may have had some ideological flaws, but they also had a lot of money to spare.

These years saw the emergence of a new format in Russian-North Korean relations, one that lasted for more than two decades. It was based on the following principles:

- On all essential North Korean issues, Moscow supports Beijing

- Externally, Moscow presents itself not as a Chinese satellite, but as an influential and independent power (whose interests just somehow always coincide with Chinese ones)

- Trade between Russia and North Korea is negligible or absent

- The parties talk about friendship, but without practical effect.

In the year 2000, at the beginning of Putin’s first term, Russia and North Korea signed a new “Treaty of Friendship, Good Neighborliness, and Cooperation.” The agreement, essentially a non-binding declaration of good intentions, was consistent with the provisions of the more detached post-Soviet relationship between Moscow and Pyongyang. Needless to say, it contained no provisions for a military alliance.

With regard to historical truth, however, Moscow has had to make concessions. Whenever the Russian president — no matter if it was Putin or Medvedev — congratulated the North Korean leader on the anniversary of Japan's surrender in 1945, he had to avoid expressions like “Red Army soldiers who brought freedom to Korea,” as such historical realities ran contrary to Pyongyang's official ideology. Thus Putin wrote in 2012 only that Soviet soldiers had “participated in the liberation” of Korea.

When experienced diplomat Alexander Matsegora was appointed as Russia's ambassador to the DPRK in December 2014, the Russian side invented a formula about “Korean patriots” who allegedly fought alongside the Red Army. Invariably repeated in Russian congratulations ever since, this wording allowed the Kims to save face while delivering Russia from the need to peddle the myth about Korea's non-existent “Revolutionary Army.”

Stage 4: Ammunition trade and a new rapprochement (2023-present day)

The Moscow-Pyongyang relations remained largely unchanged from the time of Gorbachev right through the early months of Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Throughout this decades-long period, all of Pyongyang's attempts to sweet-talk Moscow into providing economic aid were rejected by Moscow, which refused to trade resources for smiles and nice words. Even announcing the recognition of Crimea as Russian territory in 2014 had no effect. Moscow still followed Beijing's lead and voted in favor of all anti-DPRK sanctions in the UN Security Council so long as China was voting the same way.

Even with the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian war, not much changed in the relationship. Pyongyang tried to flatter Moscow by publishing statements supportive of Putin in foreign-language media (while not even mentioning the war in Ukraine in outlets aimed at its domestic audience) and by announcing the intention to recognize the so-called “Donetsk People's Republic” (and, a little later, its Luhansk counterpart). Nevertheless, the Crimean scenario repeated itself, with the North Koreans receiving only a “thank you” as compensation for their diplomatic cheerleading.

With the outbreak of the Russian-Ukrainian war, Pyongyang tried to flatter Moscow by publishing statements supportive of Putin's support in foreign-language media

Everything changed when Moscow realized that the Russian army was running low on artillery shells and that North Korea could supply such ammunition. This turn marked a new, fourth stage in the relations between the two countries.

In 2023, the trade balance between Russia and North Korea no longer equaled zero. Ammunition, and later missiles, began to be shipped to Russia from North Korean military depots en masse. In return, the DPRK received food, fuel, and money. Pyongyang has also been eager to obtain Russian missile-related and aviation technologies for its air force and strategic units.

Like the previous two milestone shifts, the beginning of a new era in the relations was marked by the signing of a new treaty. Its main feature was the renewal of the 1961 alliance commitments: the formula that “the other Contracting Party will immediately provide military and other assistance by all means at its disposal” was copied almost verbatim from the old document.

Pyongyang's major win

Without any doubt, this treaty and everything that has happened since 2023 is a major diplomatic victory for Pyongyang. On the Russia front, North Korea defeated the southern neighbor: Seoul's many attempts to pull Moscow away from Pyongyang by fostering the warmest possible friendship have been reduced to naught. Pyongyang has also begun to diversify its relations with China, making the most of its rapprochement with Russia and reversing the trend of the previous 33 years, which saw China's share in North Korea’s foreign trade frequently exceed 90%. Finally, with Moscow's alliance commitments, Pyongyang has obtained a new confidence on the world stage.

Russia’s immediate gain from the treaty may be hard to pinpoint, but it is worth remembering that Vladimir Putin's main driver is the war in Ukraine. Putin likely received an offer of additional ammunition supplies that he could not afford to turn down. We cannot rule out the psychological factor either. Putin’s dislike of North Korea was common knowledge (especially considering that it was listed as a hostile state during his service in the KGB), but Pyongyang’s constant expressions of support for his main project, the war in Ukraine, may have finally had the desired effect on the Kremlin’s longest-serving leader since Stalin.

As for the “battle of histories” between Moscow and Pyongyang, it has continued, albeit without fanfare. In his column for the North Korean newspaper Rodong Sinmun, Putin managed to sneak in a mention of “ Korea's liberation by the Red Army,” but he only did so after making a ceremonial nod to the role of “Korean patriots.” The DPRK also scored a few more small victories. On the day of Putin's visit, Rodong Sinmun extolled the efforts of the “Korean People's Revolutionary Army” in “defending the Soviet Union” against Japan in the 1930s and recalled how highly Comrade Stalin had “eulogized” Comrade Kim Il Sung. During the visit, Putin reiterated that “in 1945, Soviet soldiers fought shoulder to shoulder with Korean patriots to liberate Korea from the Japanese invaders” — although in reality no force except for the Red Army fought the Japanese in Korea in August 1945.

Vladimir Putin has repeatedly emphasized how close to his heart he holds the truth about World War II. Even before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian domestic propaganda frequently complained that the Western world was seeking to “rewrite” the history of the Soviet victory over Nazi Germany. However, the president's willingness to resort to the embarrassing formula about fictitious “Korean patriots” to please Pyongyang shows that, under certain circumstances, he is also open to compromise in the sphere of historical justice.

It remains to be seen what successes North Korea will achieve, but the talent of North Korean diplomats and the trend toward a sharp increase in cooperation should make Pyongyang optimistic. Now that North Korea is finally in a position to offer Russia something its leader wants — military supplies — there can be little doubt that Pyongyang, as always, will try to make the most of the relationship. This predatory approach is already evidenced by the fact that some of the North Korean shells turned out to be of unsatisfactory quality, at least according to Putin's “war correspondents.” As usual, Pyongyang decided that it would get away with foul play, and we can see from Putin's behavior that the plan may work.