U.S. president-elect Donald Trump built his campaign on harsh anti-immigrant rhetoric. He is not an outlier. Many European parties — not only far-right ones — leverage similar sentiments on the continent. Nevertheless, the economies of increasingly aging Western economies need immigrants more than ever if they hope to maintain the share of the economically active population — and thereby ensure GDP growth while keeping inflation in check. As for arguments about the supposed burden immigrants place on the budgets of developed countries, the actual numbers attest to the contrary.

Western populations are rapidly aging. In the U.S. and Europe, fertility fell below replacement level (2.1 children per woman) back in 1980 and now stands at 1.5 children per woman. This has led to economic issues including labor shortages and a high reliance on the shrinking working age population to support retirees. Skilled workers in key sectors such as construction and agriculture are increasingly hard to come by, and technological advances can only alleviate this problem to a certain extent.

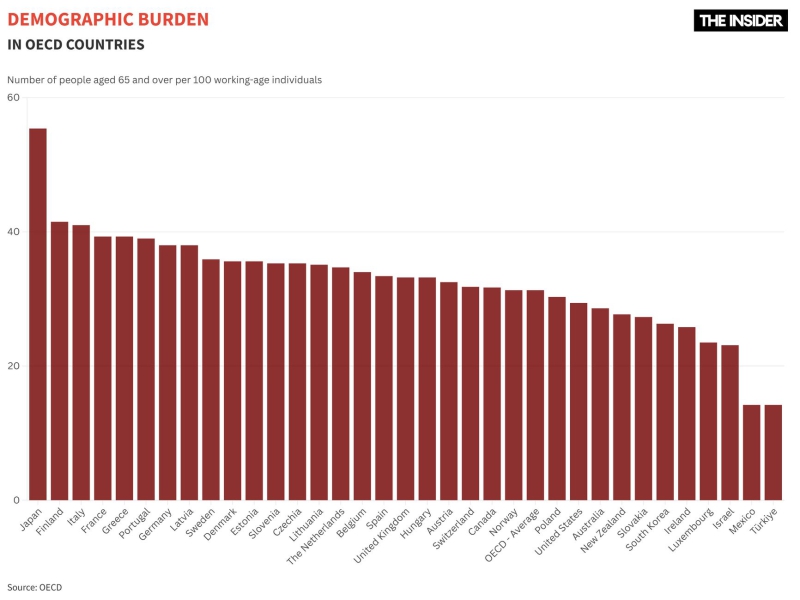

Countries with rapidly aging populations inevitably see a growing demographic burden placed on able-bodied citizens, who must cover the costs of old-age pensions with their taxes. In 17 of the 27 countries that make up the European Union (EU), annual spending on public pensions currently constitutes more than 10% of GDP. In Italy and Greece, pensions cost state budgets more than 16% of GDP. By 2050, one in three EU citizens will have passed the 65-year threshold, and the tax contributions of the working-age population will no longer be sufficient to cover their pensions.

By 2050, one in three EU citizens will have passed the 65-year threshold, and workers’ taxes will no longer cover pensions.

The U.S. population isn't getting any younger either, with nearly one in four Americans set to retire by 2050. Meanwhile, population growth rates are at historic lows, and that growth is driven mainly by immigration. The trend is fraught with huge costs in the long run, as the United States Social Security Administration predicts that, by the 2030s, the shortage in funding will be equivalent to the tax contributions of nearly 35 million. In 2034, if not sooner, all social benefits will have to be cut by at least 17%.

Combating population aging by stimulating the birth rate alone is not the answer — and it could even be dangerous for the economy, as “success” would lead to many parents leaving the labor market, thereby making the demographic burden on the remaining workers even higher.

This is why economists advise easing migration policy. Newcomers should be encouraged to officially register their labor activity and pay taxes, and removing some of the obstacles on their path into the country would help in this department. Excessively harsh restrictions, after all, only drive migrants into illegal employment.

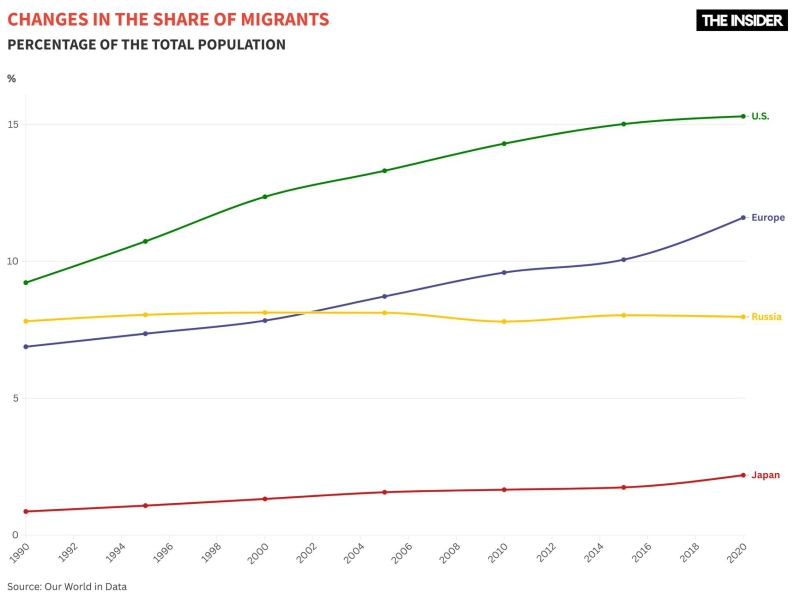

For developed western economies with a low birth rate, the case of Japan illustrates the ramifications of a strict migration policy like those favored by many right-wing politicians in Europe and North America.

The population of today's Japan is the oldest on the planet. The country has a much higher share of pensioners than Italy, which ranks second. More than 10% of Japanese are older than 80, nearly one-third are over 65, and the birth rate has dropped to 1.2 children per woman. As a result, Japan's tax revenues are on a steady decline, along with consumption, savings, and the service sector. The only developing industry is geriatric care.

The country's GDP has been stagnant since the early 2000s. Unable to fill vacancies, companies are going out of business, with the number of bankruptcies in 2024 already double what it was last year — on pace for the highest annual number since the 2008 global financial crisis. The picture is aggravated by an overtime culture that has staggered the health of the working population: nearly a quarter of Japanese companies have employees who work so much that they risk dying from fatigue.

When proposing to increase spending on children — albeit while advocating the continuation of the country’s strict migration restrictions — Prime Minister Fumio Kishida admitted that aging had brought Japanese society to the brink of survival.

Aging has brought Japanese society to the brink of survival, authorities say.

Japan accepts a very small number of immigrants. Foreigners make up only about 2% of the country's population, against nearly 6% in Europe and an astonishing 14% in the U.S. Because of nationalist policies, Japanese employers are forced to hire retirees rather than newcomers. More than 13% of the country's workers are over 65 years old, and the average Japanese farmer today is almost 69. But employing older workers only provides temporary relief. The number of able-bodied citizens in Japan is projected to continue shrinking along with the population: if the current rate is maintained, by 2040, the country will be short 11 million workers. And while Japan has taken steps in recent years to open its doors to temporary laborers from nations like Vietnam, these measures alone cannot save the country from slow extinction.

At the same time, Japan is one of the world's most technologically advanced economies — a fact that demonstrates how technological innovation alone cannot fully compensate for the problems caused by labor shortages.

In short, Japan should not serve even be considered a role model for other developed nations.

Filling vacant jobs with migrants would increase U.S. GDP by about $2 trillion, or nearly 10%, the authors of a Cato Institute study estimated. This is true for other countries as well. Population growth, including through accepting immigrants, is one of the most reliable ways for a country to increase its GDP. The costs of integrating refugees can be significant, but in the long run, they account for an additional average of 0.2-1.4 percentage points of annual GDP growth — a lot, given that average EU economy growth averages around 1.6%. This means the investment pays off in 9-19 years, the European Commission found. Spain, which is relatively open to migrants, is a good example: in 2023, immigration accounted for 64% of new jobs and half of economic growth (meanwhile, crime in Spain has halved in the past 20 years).

Migration contributed to 64% of Spain's new jobs in 2023.

The benefits of integrating highly skilled workers are clear: they increase the country's labor efficiency. However, low-skilled immigrants, who fill vacancies unwanted by locals, can also drive the economy, increasing the productivity of physical labor. Immigrants do not only increase the production of goods and services — they also tighten competition in the labor market, thus slowing wage growth and, consequently, inflation.

Consumption is another aspect through which migrants strengthen the economy of destination countries. Population growth opens up new opportunities for entrepreneurs and improves the quality of services. However, a surge in consumption also harbors risks when it comes to goods with limited supply, such as housing and infrastructure. Migrants can bring their skills to the table, but they cannot bring additional housing, roads, schools, or doctor's offices from their homelands, and while adapting infrastructure to meet the needs of a growing population in the long run also drives the economy, it takes time, which can contribute to resentment from the natives.

Consumption is another aspect through which immigrants increase the welfare of host countries.

On another note, immigration appears to have helped mitigate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Western economies. In November 2022, Jerome Powell, Chair of the Federal Reserve System, gave a speech claiming that the staffing gap in the U.S. economy would amount to 1.5 million job openings. As he argued, coronavirus had killed some 400,000 able-bodied people and undermined the health of hundreds of thousands more. Because of the coronavirus restrictions, the influx of migrants into the country had also fallen. However, only a few months later, Powell's fears were dispelled, as the U.S. labor market almost completely recovered.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman cites immigration as the primary factor in the rapid recovery: “Recent immigrants are overwhelmingly working-age adults; according to census data, 79% of foreign-born residents who arrived after 2010 are between the ages of 18 and 64, compared with only 61% for the population at large. So the immigration surge has probably been a significant contributor to the economy’s ability to continue rapid job growth without runaway inflation.”

That's in the short term, but what about the long run? Krugman continues:

“There the case for increased immigration is even stronger. If we define working age as running from 18 to 64, the overall U.S. old-age dependency ratio — calculated from the same census data — is 27.5%. For foreign-born residents who arrived after 2010, the ratio is only 5.8%. New immigrants pay into the system, but they won’t be drawing much in the way of benefits for many years to come. So the resurgence of immigration is, from an economic point of view, a good thing all around. And a rational political system, one that wasn’t being misled by false claims about immigration and crime, would welcome a sustained immigration revival.”

A similar trend could be seen in the EU, where the number of available jobs, which had surged after the pandemic in 2022, considerably dropped as immigration rose by 117%.

Internal migrants in Europe find work more successfully than natives and show a higher employment rate. By contrast, newcomers from outside the EU are less involved in the work process and occupy mostly low-skilled positions. This happens because many of them are refugees, and therefore have worse starting positions. In Germany, for instance, a refugee's chances of finding a job during the first year of stay are close to zero, as they are not even allowed to work until their paperwork has been processed. In Finland, only 22% of refugees secure employment even after 10 years of stay. In Sweden, it takes refugees about 20 years to integrate into the economy to the same degree as other migrants.

The problem is not just the abundance of red tape, but also high refugee benefits. Thus, according to the Center for Migration Studies, refugees (primarily men) found work faster when their benefits were cut. This explains why France, Italy, Germany, and other European countries have decided to cut state benefits to those fleeing their home countries: it is being done in order to encourage them to find employment in the country of refuge.

In the U.S., the level of socio-economic security for newcomers is lower and the incentives to work are correspondingly greater. As a result, refugees catch up with other immigrants in employment rates after only two years, during which nearly 60% of them find jobs. Overall, 77.5% of America's migrants are employed, compared to 66.1% of natives. In Europe, the opposite is true: only 63% of immigrants work, while the employment rate among natives is 77%. However, the picture varies internally within the EU. In Croatia, for one, where migrants receive unusually low support by European standards, about 80% of all foreigners are employed, compared to 70% of locals.

In the U.S., refugees catch up with other immigrants in employment rates in two years.

However, drastic cuts in social welfare allowances can be dangerous. A new study by European economists suggests that, while benefit cuts do push refugees into employment, they almost halve average newly working family’s income, leading to higher crime rates and lower educational attainment among children.

A less painful solution is to lower bureaucratic thresholds, ease the procedure for obtaining a work permit, help migrants overcome the language barrier, and fight discrimination, which significantly slows down integration.

In the U.S., immigrants contribute significantly to the country's budget, paying nearly $1 trillion in taxes a year, while government spending on them is $300 billion less — in part because they are often excluded from key benefits. In Europe, however, the amount of taxes paid by migrants roughly equals the cost of the benefits they receive, meaning that the net financial impact of immigration is minimal. According to a TransEuroWorks study, in European countries with lower welfare benefits, such as Belgium, Greece, and Italy, migrants put even less strain on the country's budget than locals.

In Europe, the amount of taxes paid by migrants roughly equals the cost of benefits they receive.

Nevertheless, whereas the economic benefits of migration are obvious, migration policy is often much more influenced by political and cultural factors. But there is another way. The cultural integration of migrants can be achieved provided there is the political will to ensure that newcomers receive access to education, are allowed to participate in public life, are given necessary support in the labor market, and are granted protection of their rights in general.