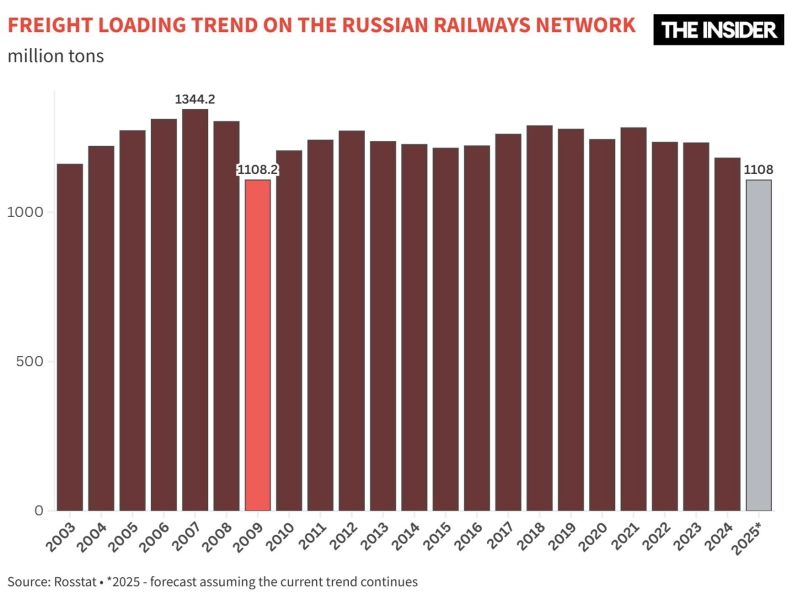

While official forecasts still predict at least modest growth for the Russian economy this year, a far more telling picture emerges from an examination of railway statistics, which show that freight volumes have fallen to record lows. The collapse points to a crisis already unfolding in civilian sectors such as coal mining, metallurgy, car and machine manufacturing, and housing construction. The data indicate a sweeping, simultaneous decline across 20 of 24 key industries. Nevertheless, the Bank of Russia continues to insist there are no signs of a recession, claiming instead that the economy is merely overheated.

The volume of freight transported by Russian Railways is decreasing. In the first nine months of 2025, cargo loading dropped by nearly 7 percent, or 60 million tons. Given that an average freight car holds just under 100 tons, this means around 600,000 cars have been freed up. At roughly 14 meters each, those empty cars would form a train stretching 8,400 kilometers — from Moscow to the Pacific Ocean.

The 2024 calendar year already saw the lowest freight loading numbers in Russia since the financial crisis year of 2009. If, by the end of 2025, volumes fall by a year-on-year total of 6.2 percent or more, the volume of cargo transported by Russian Railways would then be the lowest since 2003.

An indicator that does not exactly match freight loading but is close; it includes relatively small volumes of imports and transit.

From January to September 2024, 889.7 million tons were loaded onto RZD railcars. During the same period in 2025, the figure was 830.2 million tons, down 6.7%.

The benefits of subsidies are always shared between the direct recipient and related sectors, partly passed “up” or “down” along the supply chains. Borrowers received loans at below-market interest rates. Banks gained from higher volumes of standard operations and the advantages of scale. Developers benefited from an artificially inflated demand and rising prices. In effect, for borrowers this meant that loan interest rates were artificially lowered, while apartment prices were artificially raised.

By the end of 2025, freight loading in Russia may hit a historic low.

Even container shipments — which, as economist Farid Khusainov notes, “kept growing year after year despite everything” — could not withstand the downturn. Last year, container transport increased by 6 percent, but in the first three quarters of 2025, Russian Railways recorded a 4 percent drop.

The decline is uneven: domestic shipments fell by 5.1 percent, while exports rose by 7.8 percent. Container transport, like rail freight overall, is increasingly export-oriented. For every two domestic containers, there are now slightly more than one bound for export. The share of exports is also growing in other freight categories.

An indicator that does not exactly match freight loading but is close; it includes relatively small volumes of imports and transit.

From January to September 2024, 889.7 million tons were loaded onto RZD railcars. During the same period in 2025, the figure was 830.2 million tons, down 6.7%.

The benefits of subsidies are always shared between the direct recipient and related sectors, partly passed “up” or “down” along the supply chains. Borrowers received loans at below-market interest rates. Banks gained from higher volumes of standard operations and the advantages of scale. Developers benefited from an artificially inflated demand and rising prices. In effect, for borrowers this meant that loan interest rates were artificially lowered, while apartment prices were artificially raised.

The steepest declines occurred in container shipments of cars (down 42 percent) and other machinery (down 17 percent). Meanwhile, transport of core container cargoes — chemicals, fertilizers, manufactured goods, and metal products — has remained relatively stable, even if these, too, are slightly down. Timber and paper shipments, on the other hand, showed a small increase.

Traditionally, more than three-quarters of Russian Railways’ freight loading comes from the “big six” categories: coal, oil and petroleum products, iron and manganese ore, construction materials, fertilizers, and ferrous metals. In 2025, only one of these — fertilizers — showed modest growth. Three hree saw moderate declines, while two (construction materials and ferrous metals) suffered a major collapse.

Overall, out of 15 freight categories tracked by Russian Railways, only two show positive dynamics this year: fertilizers, and nonferrous ore and sulfur feedstock.

The steepest declines were in the loading of ferrous scrap (down 35 percent), ferrous metals (down 17 percent), grain (down 27 percent), industrial raw materials (down 18 percent), and coke (down 16 percent). Shipments of these goods, along with cement (down 13.8 percent) and construction materials (down 13.1 percent), have dropped so sharply that it clearly indicates a crisis.

In the categories of coal, oil and petroleum products, iron and manganese ore, chemicals and soda, and timber, the decline has been moderate — between 1 and 6 percent year-on-year.

In absolute terms, more than half of the total reduction in freight loading came from four groups: construction materials, oil and petroleum products, ferrous metals, and coal. Coal and hydrocarbons account for a larger share of total shipments, so even a relatively modest decline (2.8 percent for coal and 5.4 percent for oil and petroleum products) had a major impact. Construction materials and ferrous metals have a smaller share, but activity in those sectors has contracted far too abruptly.

From January to September 2025, Russian Railways carried 11.4 million tons less construction cargo and 2.5 million tons less cement than during the same period in 2024. What is behind this decline in freight volumes? Rosstat data point to reduced production. In the first nine months of the year, Russia produced 8.7 percent less cement and 5.6 percent less concrete. Output of various types of bricks fell by 6 to 13 percent, and production of ceramic tiles by 5 to 24 percent.

The decline is easy enough to explain: there is no need to produce as much construction material as before given that housing completions this year are down 5.3 percent and new construction starts have fallen by 16 percent. In Moscow and the Moscow Region, the figures for new projects are even worse — down 31 and 32 percent, respectively. This means that before long, housing completion rates will show an equally sharp decline.

An indicator that does not exactly match freight loading but is close; it includes relatively small volumes of imports and transit.

From January to September 2024, 889.7 million tons were loaded onto RZD railcars. During the same period in 2025, the figure was 830.2 million tons, down 6.7%.

The benefits of subsidies are always shared between the direct recipient and related sectors, partly passed “up” or “down” along the supply chains. Borrowers received loans at below-market interest rates. Banks gained from higher volumes of standard operations and the advantages of scale. Developers benefited from an artificially inflated demand and rising prices. In effect, for borrowers this meant that loan interest rates were artificially lowered, while apartment prices were artificially raised.

In Moscow and the Moscow Region, new construction starts are down 31 and 32 percent, respectively.

The total value of issued mortgage loans has fallen by 33 percent year-on-year, while the overall number of loans has dropped by 44 percent (meaning the average loan amount has increased). The market has contracted mainly due to the disappearance of low-budget deals. Of all current loans, 74 percent are mortgages with state support.

Over the four years of mass preferential mortgage programs, the federal government has spent more than 2.5 trillion rubles ($67.6 billion) subsidizing interest rates. Roughly half of this amount went to banks and developers, while the other half was distributed among the country’s roughly 3.5 million families receiving subsidized loans. As a result of this transfer, enormous amounts of capital were diverted from sectors where they could have generated actual returns and into economically uncompetitive housing construction.

Now that preferential mortgage programs have been mostly phased out, the housing bubble is deflating, albeit slowly. As a result, the downturn in the construction sector is likely to persist.

The decline in oil and petroleum product shipments by rail is relatively modest — 5.4 percent — but that still amounts to 8.4 million tons, or 14 percent of the total shortfall in freight loading.

“Due to refinery maintenance, the shipment of petroleum cargoes has decreased,” Russian Railways explains, without mentioning that the cause of this decline is damage from Ukrainian drone attacks. As The Insider previously reported, in the first nine months of the year Ukraine carried out 45 successful strikes on 22 oil refining and storage facilities. Experts estimate refinery output has fallen by 10 to 17 percent as a result.

Rosstat publishes only the production index for “coke and petroleum products.” From January to September 2025, this composite indicator declined by 0.5 percent. However, data for coke in physical terms show a 7 percent drop, meaning the dynamics for coke alone are worse than for “coke and petroleum products.” Therefore, for petroleum products specifically, performance must be better — or even slightly positive.

Shipments of iron, pig iron, and steel by Russian Railways fell by a critical 17 percent. Why so much? According to Rosstat, metallurgical output — including both ferrous and nonferrous metals — declined by 3.7 percent over the first nine months of the year. Production of all key items — pig iron, rolled steel, pipes — also fell. Steel showed the sharpest drop, down 15 percent.

Last year was already labeled “the worst year for metallurgists,” as steel production fell 6.6 percent, to its lowest level in seven years. Now, industry analysts describe the situation in ferrous metallurgy as a full-blown crisis — even a “perfect storm.”

An indicator that does not exactly match freight loading but is close; it includes relatively small volumes of imports and transit.

From January to September 2024, 889.7 million tons were loaded onto RZD railcars. During the same period in 2025, the figure was 830.2 million tons, down 6.7%.

The benefits of subsidies are always shared between the direct recipient and related sectors, partly passed “up” or “down” along the supply chains. Borrowers received loans at below-market interest rates. Banks gained from higher volumes of standard operations and the advantages of scale. Developers benefited from an artificially inflated demand and rising prices. In effect, for borrowers this meant that loan interest rates were artificially lowered, while apartment prices were artificially raised.

Analysts describe the situation in ferrous metallurgy as a crisis — even a “perfect storm.”

Demand for steel is falling both domestically and abroad. In the first year of the war, Russian steel came under European Union sanctions — a serious blow, since the EU had been its main foreign buyer. As a result, exports in 2023 dropped by more than a third. Exports to China almost halved as well. Meanwhile, the global market has been mired in a price war for several years, driven by aggressive dumping from Chinese producers.

In China, the construction bubble burst after the collapse of the country’s largest developer, Evergrande. Yet the production capacity of Chinese steelmakers remains intact — they still produce half the world’s steel — and, being state-owned, they operate under a logic that favors selling at a loss over cutting unprofitable output.

An indicator that does not exactly match freight loading but is close; it includes relatively small volumes of imports and transit.

From January to September 2024, 889.7 million tons were loaded onto RZD railcars. During the same period in 2025, the figure was 830.2 million tons, down 6.7%.

The benefits of subsidies are always shared between the direct recipient and related sectors, partly passed “up” or “down” along the supply chains. Borrowers received loans at below-market interest rates. Banks gained from higher volumes of standard operations and the advantages of scale. Developers benefited from an artificially inflated demand and rising prices. In effect, for borrowers this meant that loan interest rates were artificially lowered, while apartment prices were artificially raised.

About 45 percent of Russian ferrous metallurgy capacity was originally geared toward exports, according to the Russian Steel association. This year, however, the group forecasts a modest rebound from last year’s lows — by about 2.5 percent.

The domestic decline is directly linked to reduced demand from the construction sector, which accounts for 78 percent of steel consumption in Russia. Another major consumer, machinery manufacturing — particularly the automotive industry — is also contracting.

The collapse in construction has naturally led to a decline in steel production. The less steel is produced, the less coking coal is needed. The result: overall coal output in 2025 has remained roughly unchanged, but production of coking coal has dropped by 9.1 percent. Coking coal accounts for about a quarter of all coal mined in Russia, but the problems in the coal industry extend beyond this segment.

The coal industry finds itself in crisis for the second year in a row. The Energy Ministry forecasts that total losses will reach 300 billion rubles ($3.7 billion) by the end of the year — nearly triple last year’s figure.

Interestingly, coal output dynamics vary by region: production in Kuzbass is falling, while in the Far East it is rising. The Kuznetsk Basin is particularly dependent on the domestic market, where metallurgical coal use is concentrated. Foreign buyers are far away, and the rail lines leading east are overloaded.

Notably, while freight loading has dropped, the average distance of shipments has grown, meaning short-haul traffic is declining faster than long-haul traffic. That’s because short-haul shipments reflect domestic demand, while long-haul shipments are tied to exports. Domestic markets are contracting, while the Trans-Siberian Railway, the Baikal–Amur Mainline, and routes running to China or Pacific ports are operating at full capacity.

Rail shipments to China are almost entirely one-way: from January to September, 28.6 million tons of cargo were sent from Russia, while total bilateral traffic amounted to 30.4 million tons — meaning only 1.8 million tons of goods came back. Export to the east has become a last resort for many enterprises, as domestic markets increasingly show losses, project cancellations, and falling deliveries. On top of that, a VAT increase is expected to come into effect early next year.

Even according to Rosstat’s own official data, industrial output is steadily declining. “In economic terms, what’s happening in Russian industry is called a ‘frontal collapse,’” explains economist Sergei Aleksashenko. “Rosstat’s figures show that after nine months, everyone is ‘dancing the dance’ — that is, falling year-on-year — except for tobacco producers, textile manufacturers, and those sectors where military output is hidden in the statistics.”

An indicator that does not exactly match freight loading but is close; it includes relatively small volumes of imports and transit.

From January to September 2024, 889.7 million tons were loaded onto RZD railcars. During the same period in 2025, the figure was 830.2 million tons, down 6.7%.

The benefits of subsidies are always shared between the direct recipient and related sectors, partly passed “up” or “down” along the supply chains. Borrowers received loans at below-market interest rates. Banks gained from higher volumes of standard operations and the advantages of scale. Developers benefited from an artificially inflated demand and rising prices. In effect, for borrowers this meant that loan interest rates were artificially lowered, while apartment prices were artificially raised.

“In economic terms, what’s happening in Russian industry is called a ‘frontal collapse,’” explains economist Sergei Aleksashenko.

“Industry is in a borderline state between stagnation and decline,” writes the Russian Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecasting (CMASF). “Output has been falling for four consecutive months, at an average rate of 0.3 percent per month.” Analysts at the center describe this as “near-stagnation dynamics” and warn of “a risk of slipping into recession.”

The Bank of Russia, however, does not believe that the country’s industry is in a state of frontal collapse. In October, Central Bank head Elvira Nabiullina cut the key interest rate from 17 to 16.5 percent, stating that the economy “is emerging from a period of severe overheating.” Speaking before the State Duma, she said there were no signs of a recession.

“If we mechanically extrapolate the condition of a single industry or enterprise, even a major one, to the entire economy, the picture becomes distorted. That’s where talk of recession, of being on the brink of recession, comes from. I urge people to approach such statements responsibly. Because in a recession two things are inevitable: unemployment rises sharply, and then real wages fall. Neither of these is happening right now,” Nabiullina assured lawmakers.

Unemployment is indeed at a historic low, and wages are rising faster than labor productivity. Low unemployment and high inflation are, according to textbook definitions, signs of overheating — an “excess of aggregate demand,” as the Central Bank emphasizes. Yet a deeper, more substantive look at the economy must take into account not only the utilization of labor and production capacity, but also the scope of available investment opportunities, the average planning horizon, and the level of risk that businesses are willing to take on. From such a multidimensional perspective, full employment and rising wages appear to be the result of government intervention rather than evidence of genuine economic recovery.

An indicator that does not exactly match freight loading but is close; it includes relatively small volumes of imports and transit.

From January to September 2024, 889.7 million tons were loaded onto RZD railcars. During the same period in 2025, the figure was 830.2 million tons, down 6.7%.

The benefits of subsidies are always shared between the direct recipient and related sectors, partly passed “up” or “down” along the supply chains. Borrowers received loans at below-market interest rates. Banks gained from higher volumes of standard operations and the advantages of scale. Developers benefited from an artificially inflated demand and rising prices. In effect, for borrowers this meant that loan interest rates were artificially lowered, while apartment prices were artificially raised.