Big changes may be in store for the European Union: former European Central Bank president Mario Draghi, who once saved the continent from a debt crisis, has outlined an ambitious reform plan aimed at countering a potential economic slowdown and recession within the EU. Draghi suggests moving away from the current requirement for unanimous decision-making, replacing it with a simple majority vote on key issues. He also advocates implementing a unified tax system, streamlining company registration across the bloc, and easing migrant entry and integration processes. While the plan envisions a “EU 2.0,” it faces challenges, as many of its proposals clash with long-standing EU policies. Its adoption is far from certain.

In September, the European Commission published “The future of European competitiveness” — a long-awaited report by Mario Draghi, the former Italian prime minister who served as head of the European Central Bank (ECB) from 2011 to 2019. The document outlines the challenges facing the EU economy, which has lagged behind the U.S. and may soon fall behind China. Known for saving Europe from the 2012 debt crisis, Draghi was tasked by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen one year ago to share his personal vision for a better common future on the continent. Draghi’s report is set to shape the agenda for the European Commission over the next several years.

“The EU exists to ensure that Europe’s fundamental values are always upheld: democracy, freedom, peace, equity, and prosperity in a sustainable environment,” Draghi said while presenting the report. But if nothing is done now, the EU will become “less prosperous, less equal, less secure, and, as a result, less free to choose our destiny.” He warned that, “If Europe cannot any longer deliver these values for its people, it will have lost its reason for being.”

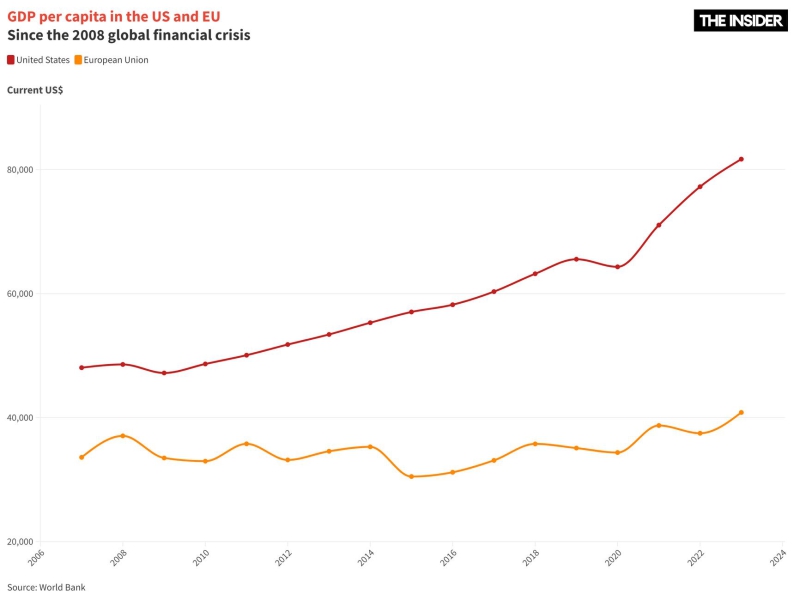

The need for change is evident from economic indicators. “On a per capita basis, real disposable income has grown almost twice as much in the U.S. as in the EU since 2000,” Draghi writes in the foreword to the shortened version of the 400-page report. This is not the only metric in which the Old World is falling further behind the New — and there is no reason to expect the trend to reverse itself.

“If Europe cannot become more productive, we will be forced to choose. We will not be able to become, at once, a leader in new technologies, a beacon of climate responsibility, and an independent player on the world stage. We will not be able to finance our social model. We will have to scale back some, if not all, of our ambitions,” Draghi warns.

An abbreviation for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (as subjects of study).

From the first pages of the report, it is clear that Draghi sees low labor productivity as Europe's main problem. Statistics show that EU workers produce fewer goods and services in the same amount of time than in the US. The gap, which is becoming more pronounced, “is largely explained by the tech sector,” which is underdeveloped in Europe.

High-tech doesn't reach the market

The core issue stems from a lack of sufficient investment in research and development, particularly from high-tech companies. In the 2000s, the top spenders on R&D in the U.S. could mainly be found in the automotive and pharmaceutical sectors. Now, however, R&D spending in America is dominated by digital firms. But the EU remains led by car manufacturers, as its economies continue to focus on “mature technologies,” offering limited room for innovation and productivity growth.

Over the past 50 years, no EU-born company has reached a market capitalization of over €100 billion from scratch, while the U.S. has produced dozens — including six with valuations exceeding €1 trillion. According to Draghi, the problem isn’t Europe’s capacity for innovation, but rather its failure to commercialize inventions. Disruptive companies looking to scale in Europe face costly and cumbersome regulations at nearly every stage. The EU currently has around 100 laws governing tech firms and 270 regulatory bodies in the IT sector. When it comes to compromises between consumer rights and business efficiency, the EU almost always sides with the consumer rather than with business.

An abbreviation for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (as subjects of study).

Over the past 50 years, no EU-born company has reached a market capitalization of over €100 billion from scratch, while the U.S. has produced dozens.

Few European countries have pension or other funds investing in the economy, and there is effectively no single capital market to support cross-border investments, leaving businesses reliant on risk-averse banks. With fewer billionaires than the U.S., Europe also has fewer venture capitalists and private investors, limiting funding for innovation. Additionally, Europe’s underdeveloped STEM education system has resulted in a smaller pool of skilled workers for tech firms.

As a result, many European entrepreneurs turn to American investors and expand into the U.S. market. Between 2000 and 2021, around 30% of “unicorns” — startups that go on to secure valuations of over $1 billion — founded in Europe moved their headquarters abroad, with the vast majority relocating to the U.S.

An abbreviation for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (as subjects of study).

Over the past 20 years, around 30% of “unicorns” founded in Europe moved their headquarters abroad, with the vast majority relocating to the U.S.

Expensive energy

Despite the fact that energy prices have significantly dropped when compared to their 2022 peaks, companies in the EU still have to pay two to three times more for electricity than their competitors in the U.S. and China do. Natural gas prices in the EU remain four to five times higher. This is largely due to Europe’s limited natural resource base and the ongoing supply challenges with Russian gas, which the region had come to depend on.

The EU is a leader in sustainable energy, but its producers and traders pay high taxes and tariffs, preventing companies and households from fully reaping the benefits of the energy transition. Without a plan to pass on the advantages of decarbonization to end consumers, elevated energy costs will continue to impede economic growth, Draghi argues.

Growing geopolitical risks

Security is essential for sustainable economic growth and investment, yet a war is unfolding near the EU's borders, leaving the bloc inadequately protected and economically vulnerable. The EU relies heavily on a limited number of suppliers for critical raw materials and advanced technologies. Nearly 90% of the world’s semiconductor chip production is concentrated in Asia — and the situation could quickly become critical if China chooses to disrupt supply. The EU also depends on China for rare earth metals crucial for green technologies and the defense industry.

As China and the U.S. work to disentangle their interdependent relationship, Draghi warns that if the EU does not follow suit, it risks becoming a victim of monopolistic suppliers.

Draghi points to disunity as the main issue holding back the EU. High gas prices, he argues, stem from the bloc not leveraging its potential as a unified buyer, while trade frictions are costing around 10% of GDP annually. Fragmented investments mean that small countries contribute a large share of their GDP to projects, while larger states invest much less.

In response, Draghi calls for greater unity and faster action. “Integration is our only hope left,” he said, warning that without it, the EU faces a “slow agony.” This echoes similar calls by French President Emmanuel Macron for a more unified Europe — though Draghi’s plea is backed by economic reasoning.

An abbreviation for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (as subjects of study).

The EU will face a “slow agony” if it does not act quickly and together, Draghi warns.

To improve decision-making within EU institutions, Draghi advocates dropping the unanimity rule in favor of qualified majority voting in the European Council on key issues like taxation, foreign policy, security, and defense. Currently, the need for consensus allows any country to block critical decisions, such as those concerning sanctions against Russia or aid to Ukraine.

Draghi also stresses the need for economic cohesion, particularly through the alignment of tax systems across the EU, a move that would prevent countries from competing for businesses by offering more favorable tax conditions. He proposes introducing a single corporate tax base and easing regulations on mergers and acquisitions in order to enable the creation of large European companies capable of competing with American corporations. This is one of the most controversial proposals in Draghi's plan, as it raises the risk of creating monopolies, and with them, higher consumer prices.

The European defense industry is fragmented, making scaling difficult. Draghi urges standardization to ensure compatibility of equipment — for instance, Europe manufactures twelve different types of battle tanks, while the U.S. produces just one. Moreover, high defense spending does little to benefit EU industries, a four-fifths of the bloc’s total defense procurement goes to suppliers outside the EU. Thus, another point in Draghi's plan is the consolidation of public spending.

On the social front, Draghi’s plan includes calls for reducing regulations in education in order to equip Europeans with the skills needed for technological development, ensuring technology and social integration progress hand in hand.

To address labor shortages and an aging population, Draghi proposes attracting skilled foreign workers. Currently, 54% of EU companies cite a lack of skilled workers as one of their most pressing problems. He suggests boosting mobility within the bloc for EU residents. Due to language, cultural, and administrative barriers, relocation within Europe remains lower than in places like the U.S. Draghi also calls for revising the list of professions requiring national certification.

An abbreviation for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (as subjects of study).

54% of EU companies cite a lack of skilled workers as one of their most pressing problems.

Draghi suggests immediate measures to attract talent from abroad. One program would target STEM students, with the introduction of an EU-wide visa system for students, graduates, and researchers, along with clear criteria for eligibility and a simplified application process. He also recommends increasing scholarships, funded in part by private companies, as well as offering internships and graduate contracts in research centers and public institutions across the EU. “Additional incentives to stay in the EU, including tax incentives and housing assistance, could be considered,” Draghi writes.

Another program would appeal to experienced professionals, with streamlined immigration procedures including faster visa and residency approvals for skilled workers. Besides the immigration procedures themselves, Draghi suggests expanding job opportunities and EU mobility programs like the Blue Card, which facilitates entry and residency for qualified professionals.

An abbreviation for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (as subjects of study).

Draghi insists that the EU immediately simplify the visa process for talented students and highly skilled professionals.

However, these reforms will come at a significant financial cost — funds will be needed for tax incentives aimed at helping startups and working parents, investments in innovation, support for European manufacturers, and education for both children and adults. Draghi, alongside analysts from the European Commission and the ECB, estimated that an additional €700-800 billion per year — around 5% of the EU’s GDP — will be required. For context, investments under the Marshall Plan, the U.S. post-World War II aid program to Europe, amounted to 1-2% of GDP. If implemented, these plans would increase the EU’s investment share from around 22% of GDP to 27%, reversing years of decline in most of the bloc's major economies.

European countries cannot allocate such sums from their budgets. Even Europe's largest economies, such as Germany and France, are currently coping with difficult economic circumstances and cannot simply cut spending or raise taxes. Therefore, to finance these reforms, Draghi urges completing long-discussed EU initiatives like creating a capital markets union and banking union to encourage private investment. However, he admits that private funding alone won’t be enough and supports public investments financed by issuing EU-wide bonds.

The provisions of the report were immediately backed by various political groups in Europe, but its publication at a moment when Germany and France find themselves in a state of political turmoil and budgetary uncertainty raises questions about the plan’s prospects.

Even under more favorable circumstances, the measures proposed in the report would have been difficult to implement. Draghi's ideas cross too many “red lines” for European leaders, and despite the fact that almost no negative economic effects are foreseen from Draghi's plan (simulations show that the only consequence could be a moderate rise in inflation due to an investment surge), Europeans are still concerned about its ethical implications.

The push for competitiveness always threatens workers' and consumers' rights, carrying with it the risk of lower wages, worse working conditions, and reduced social protections, while environmental standards may be compromised in the name of profit. “Instead of confronting the dominance of overseas corporate giants with proper anti-monopoly measures, Draghi’s plan looks set to create new corporate monsters within the EU,” argued MEP Martin Schirdewan of Germany’s Die Linke party. “This logic is deeply flawed. We should be breaking up overpowered corporations, not creating new ones.”

The issuance of new common debt proposed by Draghi has also drawn negative reactions from Germany and the Netherlands. German Finance Minister Christian Lindner immediately rejected the idea, saying that the EU’s problem is not a lack of public investment but the bureaucracy burdening businesses.

The report is set to face two key political tests. First, Draghi will present his recommendations to European leaders at the European Council meeting on Nov. 7 in Budapest — shortly after the U.S. presidential election. Draghi is expected to press EU leaders on the urgency of taking decisive action, though the outcome of the U.S. election could influence the political climate in the EU in unpredictable ways.

The second, more concrete indicator of how seriously European leaders view the report will come during negotiations on the next multiannual financial framework, which will determine the EU’s budget for 2028-2034. The first summit on this topic is expected next year, and the size of the budget, its sources of funding, and the depth of reallocation of its major expenses will show whether Draghi managed to set the bloc’s policymakers on the path to significant change.

An abbreviation for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (as subjects of study).