Profits and losses across Russian industries vary widely by sector, according to the early data from 2025. Not only has the overall “profit pie” shrunk, but what’s left of it is being carved up very differently from the pattern seen in past years: banks and businesses tied to military contracts continue to benefit, while much of the rest of the economy is faltering. Retail has slumped sharply as Russians tighten their belts. Construction firms are teetering on the brink of bankruptcy, with employees petitioning Putin for help. Coal mining is in such steep decline that a repeat of the miners protests seen in the 1990s would not come as a surprise. In regions such as Tver, wage arrears have soared. In short, in year four of the full-scale war, not even close ties to the state act as a guarantee of financial stability.

Due to the highly volatile USDRUB conversion rate seen over the past four years, figures in this article are presented only in rubles.

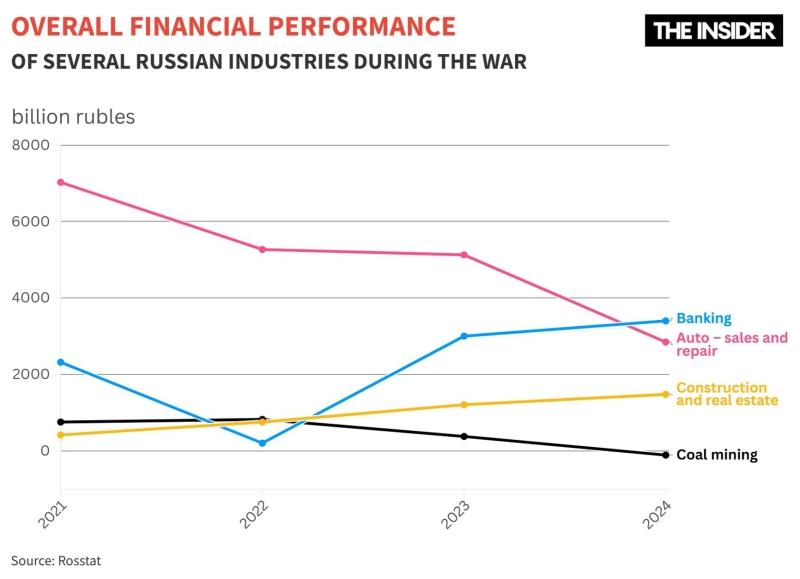

“Peace to the huts, war on the palaces,” proclaimed the radical Reds back during the Russian Civil War. In 2025, the Putin administration’s economic motto might as well be: “Peace to the banks, war on the shops.” It may not have been a deliberate policy, but the profit figures speak for themselves. Before the full-scale invasion, retail businesses earned three times more than they do now — 7 trillion rubles in 2021, compared to just 2.8 trillion in 2024. The collapse is mirrored elsewhere. Coal mining, for instance, went from a 752-billion-ruble profit in 2021 to a 113-billion-ruble loss in 2024.

Meanwhile, commercial banks saw their combined profits surge by 50%, from 2.3 trillion rubles to 3.4 trillion over the same period. Construction and real estate also saw a spike — though that appears to have been a last hurrah before the end of subsidized mortgages. Today, that sector is in serious trouble (more on this below).

According to Rosstat, the combined financial results of Russian enterprises in 2024 were worse than the previous year’s. Net profits for firms excluding banks and small businesses came to 30.4 trillion rubles, 7% below the 2023 figure.

Compared to last year, profits fell in the oil refining, chemical production, metallurgy, food processing, leather and furniture manufacturing, transport, and warehousing sectors. Meanwhile, profits increased in metal ore extraction (thanks to military demand) and in the production of computers, electronics, and optical equipment — likely driven by the surge in drone manufacturing.

Nevertheless, in 2024 commercial banks set records for net profit for the second year in a row. The volume of loans issued to companies rose sharply, though this was mostly due to ongoing investment projects and housing construction. Mortgage lending, by contrast, grew at its slowest pace ever: loans totaled 5 trillion rubles, of which 3.7 trillion were backed by state subsidies. Although mortgage support has been significantly cut back, it still plays a decisive role in the market — without it, banks would be net losers in their dealings with borrowers. Tellingly, in March 2025, unsubsidized (“market-rate”) mortgages accounted for only 29% of total issuance (33 billion rubles), while subsidized mortgages made up 67% (224 billion rubles). In other words, the state continues to pump up the mortgage market — and the banks are making the most of it.

The state continues to pump up the mortgage market — and the banks are making the most of it

Banking success is also reflected in first-quarter results. At Sberbank, both net interest income was up 15%, and net profit saw an 11% increase. VTB’s net profit rose by an even larger 15.4%.

In the retail sector, net profit dropped by 4 trillion rubles compared to 2021. Rosstat divides this sector into three categories: trade in and repair of motor vehicles (profits were cut in half over three years), other wholesale trade (down by two-thirds), and “other retail trade,” where nominal profits grew 17% over three years (although after inflation, that too amounts to a decline). This year, even nominal retail profits are expected to fall: for example, Russia’s largest retail chain, X5, saw its first-quarter net profit drop by 24%.

Russia’s largest retail chain, X5, saw its first-quarter net profit drop by 24%

Consumers are shifting to a savings-focused model. This is especially damaging for non-food retail chains, many of which have reported quarterly sales declines of 30–35% compared to last year. According to industry estimates, foot traffic in shopping centers fell 4% year-over-year, while purchases of clothing and footwear dropped 12%. Regionally, Saint Petersburg stands out in a particularly negative light: retail there ended 2024 with losses totaling 538 billion rubles.

In the first year of the war, Russia’s coal industry posted record profits — 821 billion rubles — thanks to a surge in global prices to $400 per ton, compared to the long-term average of $100. But in August 2022, the EU and UK imposed an embargo on Russian coal, and by 2023–2024, global prices had normalized — with serious consequences. In 2023, the coal sector’s net profit fell by more than half to 375 billion rubles, and in 2024, the industry as a whole operated at a loss. The last time this happened was in 2020, though back then the losses were significantly smaller. As of the end of 2024 53% of Russian coal companies were losing money, and by January–February 2025 that share had grown to 58%.

More than half of Russian coal mining companies are now operating at a loss

The problems facing Russia’s coal sector aren’t limited to prices and sanctions. Coal exports are subject to export duties that the government adjusts frequently based on global prices and the exchange rate. When it comes to exports heading eastward, nearly half the revenue is eaten up by railway transport costs, with tariffs set by the state-run Russian Railways.

In a regulated economy in which many players receive state support, the only way to avoid becoming a donor is to demand even more government aid, and that is precisely what the coal lobby keeps doing — with mixed results. The actions of Russia’s Asian customers also have not helped. Since late 2023, China has reintroduced import duties on Russian coal while keeping Australian and Indonesian coal duty free.

China taxes Russian coal while importing Australian and Indonesian coal duty free

Losses are the first step toward bankruptcy, mine closures, and layoffs. In the Novosibirsk Region, the Inskaya mine has already entered bankruptcy proceedings. Some mines operated by SDS-Ugol, Mechel, Severny Kuzbass, and Yuzhno-Anzherskaya have suspended operations. Market leaders like SUEK and Kuzbassrazrezugol are in better shape — but they are not immune to the downturn. In April, ratings agency Expert RA withdrew SUEK’s credit rating, citing “insufficient information to apply the current methodology.” Credit rating downgrades or withdrawals are a telltale sign of worsening business conditions, and in SUEK’s case, they have been accompanied by a delay in the publication of official financial reports.

The construction sector presents a paradox: overall profits are up, but results vary widely across individual firms. Some have become hotspots for wage arrears, which have risen sharply. By the end of March, overdue wages had exceeded 1.4 billion rubles — three times more than a year earlier. Non-payments grew by almost 20% in March alone, according to Rosstat. While 1.5 billion rubles may not seem like much by Russian standards — just 7,900 workers went unpaid — the pace of growth is alarming and could quickly snowball into a serious problem.

Until September 2024, overdue wage payments held steady at around 500 million rubles. But after the rollback of subsidized mortgage programs and a hike in the key interest rate, they began climbing rapidly. In January 2025, wage arrears briefly dropped, but the downward blip was short-lived.

The main reason for unpaid wages is a lack of internal funds. Construction companies account for the largest share of debtors — 40%. That’s no surprise, given that the sector was hit hardest by the end of mortgage subsidies and the accompanying rise in borrowing costs. But the geography of wage arrears is in fact unexpected: 81% of the total debt is concentrated in the Central Federal District, home to Moscow itself. Still, within the district, Tver Region is the entity that stands out: wage arrears there exceeded 750 million rubles, or 53% of the nationwide total. From January 1 to April 1, 2025, the debt owed by Tver-based employers to their workers tripled.

Most wage arrears are concentrated in central Russia, with Tver Region worst off

Moscow itself is seeing a steep rise. At the start of the year, unpaid wages in the capital totaled 59 million rubles, but three months later, that figure had surged to 370 million. If this pace continues, Moscow could soon overtake Tver as the epicenter of the problem. For now, however, Tver Region — and particularly its construction sector — remains in the worst shape. One major company in the region has repeatedly made headlines over wage delays: Dorozhnaya Stroitelnaya Kompaniya (DSK), based in the settlement of Kesova Gora, is building the Western Bridge in Tver as part of the national Safe and High-Quality Roads project. Construction began in late 2021 with an original completion date of 2024 and a budget of 11 billion rubles. That budget has since ballooned to 20 billion, and the completion date has been pushed back to 2026.

Over the past several months, DSK has delayed payments to such an extent — including to bridge construction workers — that at least two public scandals erupted, and each month sees 30–40 new enforcement proceedings opened against the company. From May to July 2024, it racked up 322 million rubles in wage arrears, leaving 4,000 people unpaid. The crisis was resolved only after government intervention.

However, according to Tver-based media citing workers’ social media posts, non-payments resumed in August 2024. Since then, builders have periodically received just 5,000 rubles each, prompting half the workforce to quit. Reports of this surfaced in December, when the Tver branch of the Investigative Committee launched a probe. No official updates have followed.

As of early May 2025, DSK is the subject of 70 enforcement proceedings over unpaid wages. All were launched this spring, with total arrears of about 18 million rubles — roughly one-thousandth of the budget allocated for the Western Bridge, which DSK is managing. Even more serious are the claims from the Main Directorate of Highways of the Nizhny Novgorod Region: the client has filed lawsuits against the contractor totaling about 500 million rubles.

The situation at DSK appears to have become so dire that company management — writing on behalf of the workforce — posted a petition to President Vladimir Putin and Federation Council Chair Valentina Matviyenko. “We, employees of DSK LLC in Kesova Gora, Tver Region, are appealing to you with a desperate plea for help,” reads the appeal, signed by 1,085 people. The petition lists various construction and reconstruction projects the company has taken part in over the decades, including the Crimean Bridge. It also contains standard declarations: the company “has contributed to efforts in Russia’s new regions,” and “many employees are fulfilling their civic duty in the special military operation zone.” The main request in the petition reads:

“We ask you to consider the possibility of providing legal and financial assistance to DSK LLC: concessional loans, participation in government support programs for businesses, or other forms of aid that would allow us to overcome our current difficulties and continue working for the benefit of Russia.”

The sense of distress is shared not only by DSK alone, but by Russia’s road construction sector as a whole. Back in December 2024, the National Association of Infrastructure Companies (NAIK) published a grim analytical report, and in late April it held an industry forum where the same issues were again raised. According to NAIK, the volume of road construction has been in significant decline since 2024, a trend expected to intensify in 2025 when construction wraps up on the M-4 and M-12 highways. NAIK estimates the sector’s total revenue in 2024 amounted to just 57% of its 2022 level.

In the previous boom years, infrastructure contractors had bought new equipment, hired more staff, and taken out loans — some with floating interest rates. Now they face the threat of bankruptcies and layoffs. Their grievances are aimed at the state, which, they argue, pays too little for their services. Construction materials are becoming more expensive much faster than the inflation rate projected by government estimates, and project profit margins range from just 2.6% to 3.3%. Both the NAIK report and the April forum warned of a growing risk of bankruptcies in the sector.

Road construction volumes plummet, companies loaded with equipment face bankruptcy

A skeptical observer might argue that road construction spending in Russia is significantly and deliberately inflated, that the officially low profit margins disguise hidden windfall profits, and that any bankruptcies would largely be intentional and declared in bad faith. But semi-state infrastructure contractors point to facts the government prefers to deny or downplay — facts that opposition economists, by contrast, emphasize.

First, in 2024–2025, the government shifted toward cutting spending on everything except the war, ending a period during which road construction had been lavishly funded. Second, actual price growth is outpacing the officially reported inflation rate. Resources in the economy are becoming scarcer, and the struggle for what remains is growing more intense.

Housing construction is also in a difficult position. The PIK Group commissioned 2.7 million square meters of housing in 2023, but only 1.7 million in 2024. Net profit for the year fell by 46% due to increased financial costs — specifically interest payments. PIK’s biggest competitor, the Samolet Group, completed 1.5 million square meters in 2023 and 1.3 million in 2024, while its net profit dropped by two-thirds. Losses at Etalon, a top-20 developer based in St. Petersburg, doubled over the year. While builders’ revenues continued to grow, their losses were driven by an even faster growth in costs — especially interest payments on loans.

Some major construction companies increased profits — for example, LSR and A101. But they managed this by promptly scaling back investment activity and starting fewer new projects. As of May 1, 2025, LSR had 1.76 million square meters under construction, down from 2.07 million a year earlier. A101’s active construction volume fell from 1.44 million to 1.24 million square meters over the same period.

In Moscow, only eight development projects were launched in the first three months of 2025, compared to 14 in the same period of 2024 and 13 in early 2023. Notably, seven of these eight new buildings are in the business or premium class; there are no standard or economy-class projects at all. Nationwide, the total volume of housing put up for sale in the first quarter was nearly a quarter lower than in the same period last year.

Rosstat’s profit figures are far less precise than those of financial statements compiled under international accounting standards, and the gap between the agency’s aggregated data and the quarterly results of Russia’s largest corporations is cause for concern. A closer look at specific companies reveals declining profits — or even outright losses — not only in the oil industry, but also in steelmaking, retail, construction, and even the tech sector.

Nonetheless, Rosstat’s numbers reflect a broader truth: the economic impact of the Kremlin’s current policies is being distributed extremely unevenly. The biggest winner, by far, is the banking sector, while at the other end of the spectrum are agriculture and extractive industries, which are taking the hardest hits. Owners of large commercial businesses still appear to be in relatively good shape — unlike small enterprises and wage earners. Few in the latter category can claim their incomes have risen — 23% over the past year.

This landscape is the result of an increasingly brutal fight for Russia’s shrinking pool of economic resources. In this environment, companies with close ties to the state are reporting record profits, while ordinary workers are increasingly often going without pay. Cries of desperation are coming even from places once sealed off from public scrutiny — like the elite circles managing road construction budgets. More than three years into the full-scale war, not even those perched atop Putin’s pyramid of corruption can count on guaranteed economic well being.