In annexed Simferopol, a recently restored Karaite kenesa — originally built in 1896 — has started to deteriorate again. Despite ample restoration efforts from 2017 to 2022, it is once more in a state of disrepair. In Kharkiv, another Karaite kenesa was struck by a Russian missile in 2022, leaving the local community with no choice but to pray via Skype. Before the full-scale war, Ukraine was home to fewer than a thousand Karaites, the smallest of Crimea’s indigenous peoples, which also include the Krymchaks and Crimean Tatars. Although they have not faced direct repression from the Russian authorities occupying their homeland, the Karaites’ unique identity is threatened by the current policy of forced Russification on the peninsula.

The first mentions of the Karaites as a religious movement within Judaism date back to the 8th century CE and originate from Persia. Documents from that period describe a group of Jewish intellectuals who decided to challenge the dominant norms within the community, particularly the authority of the rabbis. At the time, rabbis — whose readings on Holy Scripture relied heavily on the Talmud, a comprehensive commentary on the Torah — were often the only authority for Jewish communities.

From the Karaite perspective, rabbis did not help people understand the divine plan but instead conveyed their own interpretations of various issues. The Karaites rejected the authority of the Talmud and believed that the human conscience was a far better guide to truth than a collection of biblical commentaries were. The Karaites argued that the Bible alone holds all the answers to any question, even without additional commentary. The most important thing, they believed, was to have genuine faith in God, read the Torah attentively, and listen to one’s inner voice rather than the advice of rabbis.

The Karaites believed that the human conscience was a far better guide to truth than a collection of biblical commentaries were

The ideas of the Persian rebels spread rapidly across the world, and Karaite communities soon appeared in Syria, Iraq, Egypt, and other countries. The Karaites also established themselves in Crimea — according to one theory, this happened thanks to the Khazar Khaganate’s Jewish rulers, who invited representatives of various Jewish religious movements to the peninsula.

In Crimea, the Karaites adopted the Turkic language of the local population and, through close proximity and mixed marriages, culturally aligned themselves with the Crimean Tatars. Nevertheless, they preserved their distinct faith, which set them apart from both the Muslim majority and the rabbinic Krymchaks. In Crimea, the Karaites evolved from a religious community into a distinct people, diverging significantly from the traditions and customs of the Persian Empire’s Jewish milieu that had shaped them. They became successful merchants and industrialists, and just over a century ago, prosperous Karaite communities of Crimean origin existed in Kyiv, Odesa, and cities across Galicia and the Donbas. Yet they never fully assimilated into their new environment.

The wealthiest Karaite community was in Kharkiv. Local Karaites owned tobacco factories there, generating millions in revenue. In the city center, they even had an entire district of Karaite-owned houses. Now however, all that remains of the district is the kenesa building (the term translates as “place of assembly” and shares the same root as “Knesset,” the official name of the Israeli parliament). Prayers in kenesas are led by gazans, the community leaders.

After Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022, most of Kharkiv's Karaites fled the city. Some moved to safer regions in western Ukraine, others made aliyah to Israel, an many went to Poland, Lithuania, or Germany. A few have since returned, but they are the exception. According to Alexander Dzyuba, the gazan of Kharkiv’s kenesa, his community is currently enduring one of the most difficult trials in its history: “Before the war, there were thirty of us. Now, there are about ten left in Kharkiv. But it’s not always easy to keep track.” Some who had left came back, but then tensions around Kharkiv escalated again, rocket attacks resumed, and people left once more.

The kenesa building itself was also damaged during one of the missile strikes. Built over a century ago, it has long been in need of repair. After the Bolsheviks came to power, the prayer house was confiscated from the congregation. During the Soviet era, it housed the “Club of Militant Atheists,” which had time to be replaced by a driving school before the USSR finally collapsed.

By the fall of communism, the original interior of the kenesa was destroyed, and its spacious main prayer hall was split in half and converted into a two-story structure. The Karaites only regained the building in 2003. Despite its dire condition, the community has neither the funds nor the means to carry out significant repairs. For now, the kenesa waits for better days and is rarely used for prayer gatherings.

For the past few years, most prayers have been conducted online — via Skype or messaging apps. This practice began during the COVID-19 pandemic when restrictions on gatherings were in place, and it has continued throughout the full-scale war. Occasionally, members still meet in the kenesa, but not often.

In the spring of 2022, part of the building’s exterior stucco crumbled after a Russian missile strike hit central Kharkiv. Fortunately, the structure was spared serious damage, but several windows were shattered, and the facade was damaged. No one was injured, though according to Alexander Dzyuba, just minutes before the missile hit, several community members had been standing at the entrance.

The Kharkiv Karaites are not the only ones facing deadly danger. Members of this indigenous people lived and continue to live in areas that became front-line or occupied territories in February and March 2022, including the Karaites of Melitopol. Nearly all members of the local community, which was quite significant before the war, have fled. They traveled through occupied Crimea, then through Russia, and onward to Europe. Some have returned to the unoccupied part of the Zaporizhzhia Region, but most have remained in the West. In effect, the Karaite community of Melitopol has ceased to exist. “There was a community in Berdiansk, and they too, I think, almost entirely left,” says the Kharkiv gazan.

The largest and oldest Karaite community in Ukraine — the Crimean Karaites — has been living under occupation since 2014. According to Alexander Dzyuba, their small population and resulting inability to influence political processes have spared them from the sorts of mass repression and forced relocation faced by the Crimean Tatars:

“The Crimean Karaites have managed to adapt to life under occupation because they are largely left alone. The kenesa in Yevpatoria is functioning, there is a community in Feodosia, and there's a Karaite museum as well.”

Their small population and resulting inability to influence political processes have spared the Karaites from the mass repressions faced by the Crimean Tatars

At the same time, like that of the Crimean Tatars, the cultural heritage of the Karaites has fallen victim to the occupying authorities’ historical revisionism. The invaders are destroying everything that does not fit the narrative of “historically Russian Crimea” — a fact that attests to the rich cultural and political life of the peninsula long before it was seized by Russia.

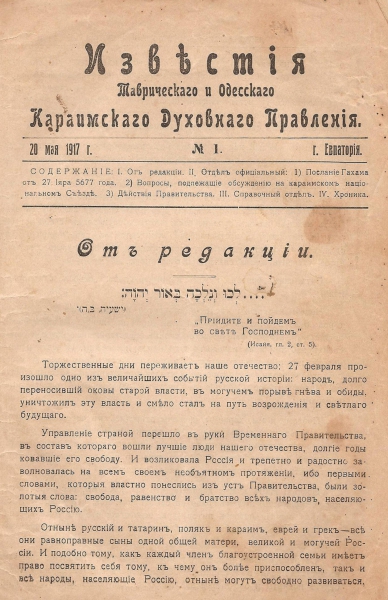

Several years before the full-scale invasion, the Karaite Spiritual Administration Newsletter, which had been published in Yevpatoria, stopped coming out, and one of the websites dedicated to Karaite history also disappeared. During the restoration of the kenesa in Simferopol, authentic doors, window grates, and other elements were damaged and ultimately replaced with “new replicas.” As Dzyuba explains, “the repairs were done by the same company that is currently involved in the so-called restoration of the Khan's Palace in Bakhchisarai.”

The former director of the Khan's Palace, Elmira Ablyalimova, has stated that the Russian authorities are destroying important pieces of the palace — those that testify to the Crimean Tatar origins of the structure. Under the guise of carrying out restoration, the occupiers are replacing historical elements with “new replicas” created without regard for the architectural traditions of the Crimean Tatars.

Under the guise of restoration, the Russian authorities are destroying important elements of the palace that testify to the Crimean Tatar origins of the structure

In other respects, the current occupying authorities are trying to treat the Karaites in much the same way the imperial government did more than a century ago. Before the 1917 revolution, the Karaites were viewed by the authorities in St. Petersburg as a marginal group that could be showcased to foreigners as evidence that the rights of small nations were not being violated and that religious freedoms in Russia were not being curtailed.

When Stalin's authorities deported the Crimean Tatars in 1944, many Karaites were displaced — especially from mixed families — and those who remained quickly began to forget their native language, as they spoke it primarily with their Crimean Tatars neighbors, who provided the everyday context for its use. The Karaim and Crimean Tatar languages are very similar. Karaim can be studied using textbooks on Crimean Tatar. When the Crimean Tatar linguistic environment disappeared and was replaced by a Russian one, the Karaites began to communicate with their neighbors in Russian. The Karaim language faded from the markets, there were no more Crimean Tatar classes in schools, and the Karaites rapidly underwent Russification.

When the Crimean Tatar linguistic environment disappeared and was replaced by a Russian one, the Karaites began to speak Russian with their neighbors

The present day Kremlin authorities’ Russification of Crimea poses a direct threat to Karaite identity. However, Alexander Dzyuba argues that the defining factor for belonging to the Karaite community is not knowledge of the language — or even the presence of Karaite ancestors — but faith:

“As long as there are keneses and communities, the Karaites will continue to exist. They may be assimilated and may not know a word of their native language, but they will have an understanding of what it means to be Karaite, that they belong to Karaite heritage, and that the Torah belongs to them. It's no coincidence that before the revolution, a common saying among Karaites was, 'There is no Karaite without the Torah.' Without it, the entire national structure collapses. Here, even language will not help if there is not the foundation — the Karaite religion.”

The Torah is so important to the Karaites that even their name is derived from it. The word “Karaim” translates to “reader,” or “one who reads,” meaning someone who follows the written word — the Torah. The Talmud, on the other hand, originally emerged as an oral commentary on the sacred text and is even referred to as the Oral Torah. In earlier times, the Karaites studied the Talmud but never recognized it as part of divine revelation.

At the same time, Israel recognizes the Karaites as Jews to the same extent it recognizes the much larger community of Jews who adhere to the Talmud's prescriptions. This recognition allows the Karaites to obtain Israeli citizenship and move to the Middle East. Most Karaites from Ukraine and neighboring countries have taken advantage of this opportunity and relocated to Israel, where the largest Karaite community in the world currently exists. However, in the case of the Karaites, “largest” still means only a few thousand people.

Most Karaites from Ukraine and neighboring countries have relocated to Israel

“Recently, many converts have been coming to our faith. And it’s not just people from Crimea or other regions of Ukraine. I know of new converts from Brazil and even Papua New Guinea. Karaite communities have recently emerged there. This is very encouraging. It means that the Karaite people will continue to exist, partly thanks to these converts,” Dzyuba says with joy.

Interestingly, Dzyuba himself is a convert, and he stumbled upon the Karaite faith by chance. While on vacation in Crimea in 2005, he visited the kenesa in Yevpatoria, struck up a conversation with the local gazan, and became captivated by the liberal and human-centered nature of the Karaite religion. He returned to his hometown of Kharkiv as a believing Karaite.

Dzyuba believes that the future of the Ukrainian Karaite community lies with people like him: “The main key to our survival is moving away from ethnic Karaism. When the principle shifts from ‘I am Karaite because my ancestors were Karaite’ to ‘I am Karaite because the Torah is the truth,’ then there will be nothing to worry about.”