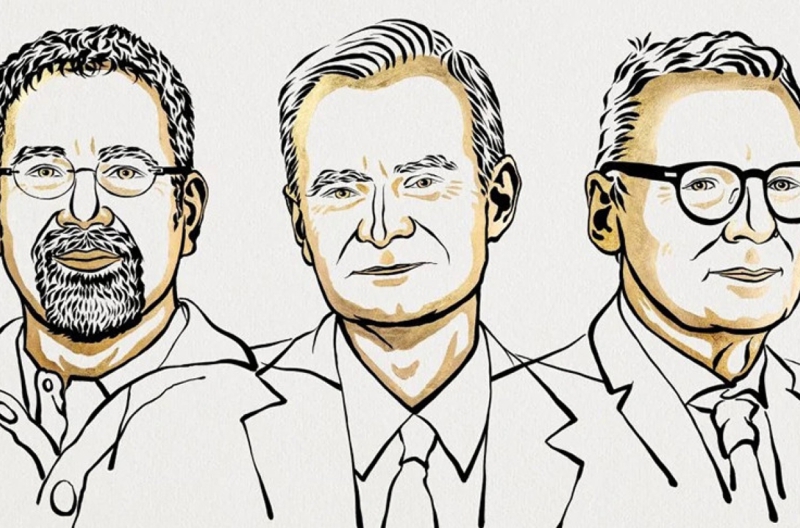

This year’s Nobel Prize in economics has been awarded to three social scientists who have managed to prove that strong institutions and a democratic society are conducive to sustainable social and economic growth — along with their population’s wellbeing. The Insider reached out to two well-known economists for an explanation about why Daron Acemoglu, James Robinson, and Simon Johnson’s research into the importance of open institutions is so pertinent to the task of fostering sustainable development in today’s world.

The most famous book written by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, who shared this year’s Nobel Prize in economics with Simon Johnson, is “Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty.” The work, published in 2012, contrasts two types of social institutions: extractive, which exclude most of society from political decision-making and income distribution, and inclusive, which offer the widest possible range of societal groups the opportunity to participate in economic and political life.

According to the authors, the exclusion of the broader masses of society from political decision-making is inevitably followed by an attack on the economic rights of everyone who does not belong to the relatively small group of ruling elites. Furthermore, the absence of reliable property rights, coupled with the general public’s inability to receive income from enterprises of their own making, stymie economic growth. As a result, achieving sustainable economic and social development is impossible without pluralistic political institutions, Acemoglu and Robinson argue. The Insider spoke with economists Konstantin Sonin and Georgy Egorov to find out why Daron Acemoglu, James Robinson, and Simon Johnson were awarded the Nobel Prize and how the social scientists' findings have informed our understanding of the modern world.

In their papers, the Nobel Prize winners have argued that bad institutions, like corrupt courts, inefficient regulators, and bad cops, do not emerge by accident but exist because economic elites are interested in maintaining them as a means of extracting rents.

For one, Russian tsars were reluctant to build railroads, fearing they would spread the revolutionary spirit. Elsewhere, rulers hampered the development of education, refusing the poorer classes the benefits of enlightenment, as doing so allowed for more rent to be extracted from the products of their labor.

In their work, Acemoglu and Robinson show that bad economic institutions correspond to bad political institutions. It takes a dictatorship to keep slavery, monopolies, and bans on innovation in place. Under a dictatorial regime, certain groups of people are prevented from voting, or their votes are not counted. Twenty-first-century Russia perfectly illustrates their theory of destructive institutions.

Another important question is: where do the institutions that foster growth come from? If we examine a country’s development and observe that everything is good, it is hard to establish a causal relationship: did the economy grow because the country had good laws, or were the good laws passed as a consequence of increased prosperity? Some backward theories insist that democracy follows the accrual of wealth. However, Acemoglu and Robinson showed, using statistics, that the correlation is inverse: wealth stems from democratic institutions, rather than institutions arising after wealth.

Together with Simon Johnson, they co-authored a famous paper describing the emergence of good institutions. They examined the climate in the territories conquered by European colonists and noticed patterns, which they managed to confirm by analyzing historical data. Where the climate was favorable, colonists settled with their families and arranged everything necessary for a decent life: they created laws, institutions, and courts, and they included native peoples in these efforts. But where the climate was tough, colonists were only concerned with taking all the surplus and did not try to build up the conditions for living. The positive institutions that had been created in the Western world never reached those latter colonies. Using such examples, the researchers proved that poor countries where good institutions were created showed growth later on. Meanwhile, countries where colonists simply extracted resources showed no growth. And even the ones that were originally rich have now become poor.

The book “Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty” became a bestseller in Russia and was never censored — which is strange, because Putin's Russia fully confirms Robinson's ideas. First, democratic institutions were dismantled, along with the system of checks and balances. Then stagnation began, and now everything has spiraled down into war.

U.S. scientists Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson have won the Nobel Prize for proving a causal relationship between the quality of public institutions and a country's prosperity. Take Denmark, for instance: a rich country with strong institutions. And then, there are countries where both the institutions are bad and the population is poor. Correlation is visible to the naked eye, but causation is not.

Democracy and inclusive institutions promote economic growth. As an example of inclusive institutions, we could cite those developing the right to private property. A variety of mechanisms enable people to invest money without fear of losing it, or at least to assess their risks as economic rather than political. That is, people may be afraid of not finding a buyer for the product they invested in due to a marketer's mistake, but not of the dictator coming along and taking everything away. Another inclusive institution is the free exchange of ideas and thoughts. People should not be afraid to speak out. This is how new ideas are born in society — and these ideas often foster prosperity.

It is naive to think there might be some perfect institutions that lead to optimal economic growth and that we should experiment until we find their best combination. That's not going to happen in the next few decades, or maybe ever.

The results of the works that earned these authors the Nobel Prize are positive in the sense of showing that throughout human history, countries with better institutions have grown faster, and those with worse institutions have grown slower. Whatever happens to institutions in the coming decades, it is this research that we will be validating.

There is a difference between situations where countries of the Global North impose their institutions violently (like the U.S. invading Iraq and trying to transform it into a democracy) and the natural development of institutions through dialogue and processes within society. In my understanding, if people in Iraq associate American democracy with human rights but struggle to find food for tomorrow, it leads to some kind of internal resistance. And the bigger the gap, the higher the resistance. On the other hand, if we are talking about organic support for democratic institutions, it will only grow.

Imagine sitting in East Germany and watching West German channels and commercials for their products. Or people in the Soviet Union watching Western movies and imagining life in the West. The bigger the gap, the greater the realization of the shortcomings of the existing regime and the greater the thirst for change. I believe that the wealth gap between North and South will cause people in the Global South to seek change. A more volatile situation may arise if the countries of the North choose to slow down growth for various reasons, such as environmental concerns. And if the living standards of the South were to approach those of the North, people may doubt whether democracy and human rights are needed at all.

If the West, or the Global North, sacrifices some of the freedoms for some ideas, it will inevitably lead to economic slowdown and underdevelopment. Good institutions lead to higher economic growth in the long run. This is the key takeaway. This does not mean, however, that institutions are the only determinant of growth. The country's human capital and its geographical and geopolitical location are also important.

Can a dictatorship create institutions that increase welfare without threatening the regime itself? Yes and no. Indeed, some dictatorships understand the importance of institutions — such as property rights, which are necessary for people to innovate, patent their inventions, invest, build businesses, and so on. They encourage individuals to do all of the above, but only within the existing political model. The Emirates, Singapore, Russia’s “sovereign democracy,” and China have done so. It's certainly better than nothing — a dictatorship that realizes the pitfalls of medieval-style tyranny seeks to produce at least some economic growth, if only to maintain its grip on power.

There's a personality factor involved. Individuals like Lee Kwan Yew (the first prime minister of Singapore) created countries, rules of the game, and institutions that sustained economic growth for decades. These could be some internal institutions of power succession. Until recently, China's leaders changed every ten years. Admittedly, China is no democracy, but the succession of power mimicked democracy in a way. It all worked until Xi Jinping came about. What's the conclusion here? Indeed, non-democracies often try to emulate good institutions and even succeed to some extent. The problem is that in the absence of truly democratic institutions, all good things tend to come to an end. Lee Kuan Yew is not eternal, and the Chinese system is not eternal either.

The advantage of democracy is that it provides institutional stability in the long run. Daron, Simon, and Jim's main idea is not that democracies are always better than dictatorships. The idea is that in the long term, countries with strong institutions generally outperform countries with poor institutions, particularly because economic and political institutions provide stable rules and reduce the historic significance of individuals and the impact of chance.

There is a global consensus on the findings of Nobel Prize winners in economics on the impact of institutions on countries' prosperity. As for the extent of this influence, opinions vary even within the academic community. Some think that institutions may be great, but human capital, education, and a country's openness to global markets play a much bigger role. The consensus is that institutions are a good thing. The choice of the method of growth — and whether there could be a one-size-fits-all approach — will always remain up for debate.

Why do bad institutions become self-sustaining? It’s not that people have no idea what institutions might be good or what needs to be done. The reason is that social groups with political power and economic influence stand to lose from the emergence of good institutions. Such groups are interested in maintaining their wealth, not building institutions that will overturn their boat, even if they would also lead to growth in the country as a whole. In particular, for example, social mobility plays an important role.

Social mobility is good for institutions. You don't need good institutions if you have power or property. Moreover, you may be afraid of losing that power in the event that the institutions become good. If you are a major landowner, your children and grandchildren will be landowners too — so you don't want to create institutions that reduce the political weight of landowners. You will be interested in maintaining the status quo — but only provided that social mobility is low. That is, if you're rich, your children and grandchildren will most likely be rich. If social mobility is high, you are more interested in what helps the average person. In this case, you have more incentives to preserve and maintain good institutions. Social mobility increases the interest of all strata and all social groups in the well-being of the average person, and the only way to support this is to invest in good institutions.