While much of Syria celebrates the fall of the Assad regime, the mood in the country’s north is grim. Seizing the moment of chaos, Turkey and its proxy, the Syrian National Army, have launched a large-scale offensive against the region’s Kurds. In just a matter of days, the autonomous region has lost two significant cities: Tell Rifaat and Manbij. For the past decade, the Kurds have operated in Syria as a de facto quasi-independent state. However, the new Syrian authorities from Hayat Tahrir al-Sham are now in talks with Turkish officials, openly discussing the disarmament of Kurdish forces. Turkey has long been determined to crush the Kurdish separatist movement, but the Kurds continue to receive support from the United States, which sees them as indispensable allies in the fight against ISIS. Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether Washington is willing to support its partners in the event of a direct confrontation with Turkey.

Sources from territories under the control of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), whose core consists of Kurdish fighters, report that more than 100,000 refugees have fled cities seized by pro-Turkish proxy forces. Witnesses describe widespread atrocities in recently captured areas, with daily clashes claiming dozens more lives.

At the same time, the new Syrian authorities, represented by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), are negotiating with Turkish officials to push for the disarmament of the SDF. This region, renowned globally for its brave Kurdish men and women — who stood against ISIS — now faces the grave risk of losing the autonomy they fought so hard to achieve.

Thirty-year-old Kurdish woman Berivan, along with her friends, traveled to the main square of Qamishlo (known in Arabic as Al-Qamishli), one of the region's largest cities, to celebrate the fall of the Assad regime. They wanted to witness firsthand the removal of Hafez Assad's statues and the tearing down of the faded portraits of his son, the deposed dictator Bashar.

In 1962, the Ba’ath Party conducted a census aimed at identifying non-Arab populations in order to facilitate the «Arabization» of Kurdish territories in Syria. Non-Arabs were required to prove that they had been living in Syria since at least 1945. Those who could not provide such proof were classified as «foreigners» and stripped of Syrian citizenship. They were issued documents that explicitly prohibited their holders from residing in the Al-Hasakah Governorate. The government also expropriated Kurdish lands and deported the former owners. The authorities constructed free housing in these areas for ethnic Arabs and encouraged them to take up agriculture. This policy, devised by the Ba’ath Party, became known as the «Arab Belt.»

However, the women repeatedly check their news feeds, anxiously discussing the latest developments. One of Berivan's friends shows a video on her phone of two young women in bloodied military uniforms, likely prisoners of war, being interrogated. The militants shout at them, “Are you Arab or Kurdish?”

“I don’t know them,” Berivan says, shaking her head. Then, handing her phone to her friends, she adds, “But I think I’ve seen them a couple of times.” The video she shows depicts militants loading prisoners of war into the bed of a pickup truck. One of them, a visibly exhausted woman in uniform, is thrown over a militant’s shoulder like a sack.

In early 2016, Berivan ran away from her parents' home to join the Women’s Protection Units, an all-female Kurdish armed group. After participating in several operations against ISIS in Manbij, a city in northern Syria’s Western Kurdistan region, she decided that the military path wasn’t for her. According to Berivan, she was never interested in politics; she only wanted to escape her parents’ relentless pressure to get married.

In 1962, the Ba’ath Party conducted a census aimed at identifying non-Arab populations in order to facilitate the «Arabization» of Kurdish territories in Syria. Non-Arabs were required to prove that they had been living in Syria since at least 1945. Those who could not provide such proof were classified as «foreigners» and stripped of Syrian citizenship. They were issued documents that explicitly prohibited their holders from residing in the Al-Hasakah Governorate. The government also expropriated Kurdish lands and deported the former owners. The authorities constructed free housing in these areas for ethnic Arabs and encouraged them to take up agriculture. This policy, devised by the Ba’ath Party, became known as the «Arab Belt.»

Kurdish woman Berivan ran away from home and joined the Women’s Protection Units in order to escape her parents’ relentless pressure to get married

Today, Berivan works as a tattoo artist and has a growing clientele. However, the rise to power of militants from HTS, the former Syrian branch of al-Qaeda, along with the escalating war between the Kurds and pro-Turkish forces, leave her deeply concerned about the future. “Soon, my work, my past, my identity, and even my uncovered hair might all become haram again,” she says.

The largely Kurdish SDF is now entirely focused on countering attacks by the Syrian National Army (SNA) and Turkish airstrikes around the already-captured city of Manbij and the nearby Tishrin Dam. The death toll from daily operations has already exceeded 200. To repel the attacks, the SDF had to redeploy troops who were guarding prisons holding ISIS militants and move them to the front lines to fight against the SNA and Turkey.

In 1962, the Ba’ath Party conducted a census aimed at identifying non-Arab populations in order to facilitate the «Arabization» of Kurdish territories in Syria. Non-Arabs were required to prove that they had been living in Syria since at least 1945. Those who could not provide such proof were classified as «foreigners» and stripped of Syrian citizenship. They were issued documents that explicitly prohibited their holders from residing in the Al-Hasakah Governorate. The government also expropriated Kurdish lands and deported the former owners. The authorities constructed free housing in these areas for ethnic Arabs and encouraged them to take up agriculture. This policy, devised by the Ba’ath Party, became known as the «Arab Belt.»

Beyond its role as a critical source of electricity in northeastern Syria, the Tishrin Dam is also a key crossing point over the Euphrates River, providing access to the city of Kobani. Kobani holds immense symbolic significance for the Kurds. On July 19, 2012, it became the first city in the region to declare freedom from the Assad regime, and in 2015, it was first city where ISIS suffered defeat. Now, according to SDF commander Mazloum Abdi, Kobani is under threat of attack by Turkey, which the Kurds accuse of covertly escalating the ongoing war.

In 1962, the Ba’ath Party conducted a census aimed at identifying non-Arab populations in order to facilitate the «Arabization» of Kurdish territories in Syria. Non-Arabs were required to prove that they had been living in Syria since at least 1945. Those who could not provide such proof were classified as «foreigners» and stripped of Syrian citizenship. They were issued documents that explicitly prohibited their holders from residing in the Al-Hasakah Governorate. The government also expropriated Kurdish lands and deported the former owners. The authorities constructed free housing in these areas for ethnic Arabs and encouraged them to take up agriculture. This policy, devised by the Ba’ath Party, became known as the «Arab Belt.»

In the official documents of the Assad regime, the city of Kobani was given the Arabic name Al-Arab, and other cities in northeastern Syria were also renamed. For example, the city of Derik was officially called Al-Malikiyah, named after Ba’ath Party Colonel Adnan al-Maliki. Under the Ba’ath regime, all things Kurdish were prohibited. Speaking Kurdish in the workplace was forbidden, and giving children Kurdish names was banned. Berivan’s parents had to pay a $300 bribe to local officials to register her with a Kurdish name. Naming a store in Kurdish was even more expensive — $500.

In 1962, the Ba’ath Party conducted a census aimed at identifying non-Arab populations in order to facilitate the «Arabization» of Kurdish territories in Syria. Non-Arabs were required to prove that they had been living in Syria since at least 1945. Those who could not provide such proof were classified as «foreigners» and stripped of Syrian citizenship. They were issued documents that explicitly prohibited their holders from residing in the Al-Hasakah Governorate. The government also expropriated Kurdish lands and deported the former owners. The authorities constructed free housing in these areas for ethnic Arabs and encouraged them to take up agriculture. This policy, devised by the Ba’ath Party, became known as the «Arab Belt.»

Berivan’s parents had to pay a $300 bribe to local officials to give her a Kurdish name

The Ba’ath regime made repeated but unsuccessful attempts to suppress the national liberation sentiment among Syrian Kurds, many of whom had relatives in Kurdish-populated regions of Turkey. In 1973, Hafez Assad ordered the creation of an “Arab Belt” along the border. Kurds were stripped of Syrian citizenship and forcibly relocated to Arab cities such as Raqqa, where special settlements were established. Conversely, Arabs were resettled in towns along the Syrian-Turkish border, traditionally home to Kurds, Assyrians, and descendants of Armenians who had fled genocide at the hands of Ottoman Turkey in 1915-1917.

In the 2010s, after the regime in Damascus lost its capacity to control northeast Syria, predominantly Kurdish authorities restored Kurdish names, opened Kurdish-language schools, and made Kurdish an official language — alongside Arabic — both in Kobani and in nearby cities. The region became known as Rojava, meaning “west” in Kurdish, symbolizing the western part of the wider historical Kurdish homeland, which stretches into Turkey, Iraq, and Iran.

With the rise to power of pro-Kurdish armed groups in 2012, the Assad regime's presence in the region became largely symbolic. Since then, administrative tasks have been handled by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, officially recognized only by the Catalan Parliament, while all military structures in the region are controlled by the pro-Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces.

The new authorities introduced sweeping reforms across all sectors, implementing a 50% gender quota for all positions and institutions, strengthening the prohibition of child and forced marriages, and enforcing penalties for polygamy. They quickly restored basic services by opening hospitals and addressing electricity shortages through the purchase of generators.

In 1962, the Ba’ath Party conducted a census aimed at identifying non-Arab populations in order to facilitate the «Arabization» of Kurdish territories in Syria. Non-Arabs were required to prove that they had been living in Syria since at least 1945. Those who could not provide such proof were classified as «foreigners» and stripped of Syrian citizenship. They were issued documents that explicitly prohibited their holders from residing in the Al-Hasakah Governorate. The government also expropriated Kurdish lands and deported the former owners. The authorities constructed free housing in these areas for ethnic Arabs and encouraged them to take up agriculture. This policy, devised by the Ba’ath Party, became known as the «Arab Belt.»

Kurdish authorities strengthened the prohibition of child and forced marriages, and enforced penalties for polygamy

The years of the Syrian civil war brought major transformations to the military dynamics of northeastern Syria. As the Kurds achieved military successes against ISIS, and as their administrative system developed, increasing numbers of Arab tribes linked up with pro-Kurdish groups. This led to the formation of the SDF, which includes Assyrians and Armenians, though Arabs now make up the majority.

The Syrian regime lacked the resources to reclaim Rojava, and ISIS was nearly defeated. However, the region faced a far greater threat — Turkey. During the civil war, Turkish authorities repeatedly asserted claims over Syrian territories under the pretext of “national security.”

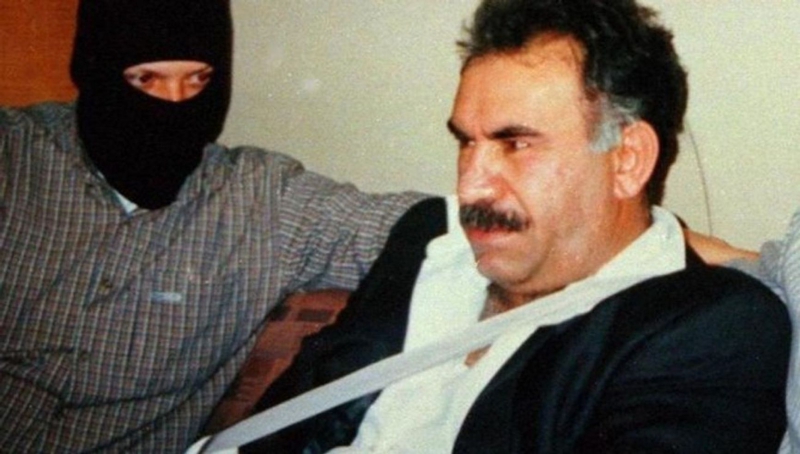

Many Kurdish leaders in the region are adherents of the ideology of Abdullah Öcalan, founder and leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). The PKK, recognized as a terrorist organization in many countries, has waged a guerrilla war against Turkey for nearly half a century, striving for a resolution of the “Kurdish question” in the form of the creation of an independent Kurdish state.

In 1962, the Ba’ath Party conducted a census aimed at identifying non-Arab populations in order to facilitate the «Arabization» of Kurdish territories in Syria. Non-Arabs were required to prove that they had been living in Syria since at least 1945. Those who could not provide such proof were classified as «foreigners» and stripped of Syrian citizenship. They were issued documents that explicitly prohibited their holders from residing in the Al-Hasakah Governorate. The government also expropriated Kurdish lands and deported the former owners. The authorities constructed free housing in these areas for ethnic Arabs and encouraged them to take up agriculture. This policy, devised by the Ba’ath Party, became known as the «Arab Belt.»

While Öcalan remains in near-total isolation in a specially constructed prison on Turkey’s Imrali Island, his portrait adorns administrative buildings across northeastern Syria. The region’s residents frequently hold demonstrations in support of him and the PKK. Although the PKK denies direct involvement in the region’s internal affairs, all new SDF recruits undergo ideological training based on Öcalan’s teachings.

The situation for Kurds in Syria worsened dramatically in 2018, when Turkey seized the Kurdish-populated Afrin region the day after the withdrawal of Russian troops. By late 2019, following the withdrawal of U.S. forces, Turkish occupation extended to the cities of Serekaniye (Ras al-Ain in Arabic) and Gire Spi (Tel Abyad). Under a ceasefire agreement brokered by Russia, the Turkish army and Russian military police jointly patrolled villages from Kobani to Dirbasiya.

Local residents were less than pleased, often pelting Russian military vehicles with stones. In response, Russian forces fired warning shots into the air and drove into the protesting crowds. The ceasefire was largely ignored: shelling by Turkish forces along the contact line resulted in the widespread destruction of civilian infrastructure and residential homes, along with multiple civilian casualties. Turkish drone strikes — including in residential neighborhoods — became part of a grim routine.

“When I learned that Assad’s soldiers and Russian troops had left their bases in Shahba and Manbij, I immediately knew Turkey would launch an operation. I told my wife I’d be heading to the front lines. I promised her it would be the last time,” says Mazlum, a father of four and a commander in the SDF, who spoke with The Insider. Mazlum is currently back on the front lines near the city of Manbij, close to the Tishrin Dam, coordinating operations. He has 13 years of war behind him.

In 1962, the Ba’ath Party conducted a census aimed at identifying non-Arab populations in order to facilitate the «Arabization» of Kurdish territories in Syria. Non-Arabs were required to prove that they had been living in Syria since at least 1945. Those who could not provide such proof were classified as «foreigners» and stripped of Syrian citizenship. They were issued documents that explicitly prohibited their holders from residing in the Al-Hasakah Governorate. The government also expropriated Kurdish lands and deported the former owners. The authorities constructed free housing in these areas for ethnic Arabs and encouraged them to take up agriculture. This policy, devised by the Ba’ath Party, became known as the «Arab Belt.»

Five years ago, Mazlum tried to become a civilian. He laid down his weapons and found work at the municipal office in his village. He decided to renovate his house — his wife was pregnant with their fourth child. However, in the fall of 2019, just as Mazlum’s wife was due to give birth, Turkey and its SNA proxies captured their village, along with the entire nearby city of Serekaniye. Mazlum fled with his family on a single motorcycle.

Since then, they have lived in tents, with no home to return to. Mazlum is certain they made the right decision to leave:

“In my village and all the neighboring villages, not a single Kurd remains. Even elderly people who can barely walk have left. The same thing is happening now in Shahba and Manbij. The invaders even terrorize some Arabs. For us Kurds, there’s no life left there.”

Mazlum and the entire Kurdish leadership now operate underground. The SDF has spent years constructing military tunnels in areas liberated from ISIS near the Turkish border, as Turkish airstrikes are a constant threat in the region. According to the Kurds, Turkish drones regularly target civilian infrastructure. For instance, on December 19, a drone strike hit a vehicle carrying journalists Cihan Bilgin and Nazim Dashtan, who were covering events from SDF-controlled areas near the front lines.

According to Mazlum, there were extensive tunnels in Shahba and Manbij, but these cities nevertheless fell into pro-Turkish hands within days:

“There were tunnels in Shahba, but there was no one to fight in them. We lacked both fighters and weapons. That’s why the troops simply evacuated civilians wherever they could. In Manbij, our forces withdrew because of betrayal by some Arab tribes who switched sides to the SNA at the beginning of the attacks.”

The SDF has little with which to counter Turkey’s air force and the SNA’s artillery. Kurdish forces make use of improvised kamikaze drones, a tactic they learned from ISIS. The United States fully supports the SDF in their fight against ISIS, but Washington offers no assistance in their battles with the Syrian National Army or the Turkish military — the second-largest army in NATO when measured in manpower.

In 1962, the Ba’ath Party conducted a census aimed at identifying non-Arab populations in order to facilitate the «Arabization» of Kurdish territories in Syria. Non-Arabs were required to prove that they had been living in Syria since at least 1945. Those who could not provide such proof were classified as «foreigners» and stripped of Syrian citizenship. They were issued documents that explicitly prohibited their holders from residing in the Al-Hasakah Governorate. The government also expropriated Kurdish lands and deported the former owners. The authorities constructed free housing in these areas for ethnic Arabs and encouraged them to take up agriculture. This policy, devised by the Ba’ath Party, became known as the «Arab Belt.»

The United States supports the Kurds in their fight against ISIS but offers no assistance in their battles with pro-Turkish forces

Mazlum does not trust HTS, which recently came to power in Syria. He refuses to even listen to discussions about the group’s internal reforms and the promises made by its leader, the new de facto head of Syria, Ahmed Al-Sharaa (Al-Julani), who has pledged to respect the rights of national minorities: “The people who committed crimes in my village are now in power. They’re the same fighters who fought against us in 2013.”

From 2012 to 2013,Mazlum’s hometown of Serekaniye was divided into two parts — one controlled by pro-Kurdish units, the other by Jabhat al-Nusra (which in 2016 changed its name to Hayat Tahrir al-Sham). Both of these forces fought against the Syrian regime, which bombed both parts of the city. Ironically, Mazlum’s house ended up in the territory controlled by Jabhat al-Nusra. He decided to inform the Kurdish armed forces about the group's movements and plans:

“I never spoke Kurdish with anyone, never even mentioned my family or my roots. We only spoke Arabic, even at home. My wife covered herself, and I grew a beard. We were really scared, to be honest. Because they decapitated those they suspected of working with the Kurdish administration.”

Now, neither Mazlum's wife Soaad nor his eldest daughter Arin wears a headscarf. None of his children speaks Arabic fluently. Mazlum himself does not see a future for himself in the new Syria:

“Before, I couldn’t travel through Syria because the regime’s forces would arrest me for serving in the SDF and evading conscription in [Assad’s] army. Now, I can’t travel through Syria because I fear [HTS] will arrest me for the same reason.”

It should be noted, however, that since the fall of Assad’s regime, there have been no major conflicts between the SDF and HTS. The commander-in-chief of the SDF, Mazlum Abdi (not The Insider's interviewee), stated that HTS had even warned his group in advance about their march on Damascus. Despite reports of protests being suppressed — and also of torture and lynchings by the new Syrian authorities — in Latakia, Tartus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo HTS has not touched the SDF-controlled region of northeastern Syria, nor has it seriously threatened Sheikh Maqsud or Ashrafiya, the Kurdish neighborhoods of Aleppo.

In 1962, the Ba’ath Party conducted a census aimed at identifying non-Arab populations in order to facilitate the «Arabization» of Kurdish territories in Syria. Non-Arabs were required to prove that they had been living in Syria since at least 1945. Those who could not provide such proof were classified as «foreigners» and stripped of Syrian citizenship. They were issued documents that explicitly prohibited their holders from residing in the Al-Hasakah Governorate. The government also expropriated Kurdish lands and deported the former owners. The authorities constructed free housing in these areas for ethnic Arabs and encouraged them to take up agriculture. This policy, devised by the Ba’ath Party, became known as the «Arab Belt.»

HTS warned the Kurdish forces in advance about their march on Damascus

These neighborhoods are guarded by small Kurdish self-defense groups, which are also part of the SDF. Since the city was captured by HTS forces, there have been several reports of attempts to infiltrate this Kurdish enclave in Aleppo. However, none of the attacks escalated into large-scale clashes. Furthermore, due to the advance of Turkish proxies in the north of the country, Kurds are fleeing not only to the northeastern region of Syria, but also to Aleppo itself.

Amina, a 47-year-old refugee from Afrin, is one of those who fled — from Shahba, on Dec. 10, with her family, to the Sheikh Maqsud neighborhood in Aleppo. “We gathered in just a few minutes and ran toward the refugee camps set up back in 2018, after Afrin was occupied. When we were leaving Shahba, militants took our cash and my gold earrings. We were lucky. Some were just stopped and taken away in an unknown direction,” she recalls.

Amina and her family arrived in Sheikh Maqsud to stay with relatives, as they have no family in northeastern Syria. She now fears that Sheikh Maqsud will also be cleared of Kurds, meaning they may have to flee again:

“We’ve already been refugees twice. The third time, we’ll probably have to die. If HTS changes its policy towards us, they’ll reach Rojava as well. We’ll just find out about it here in Sheikh Maqsud first. We have nowhere else to go.”

As a result, many Kurds are still contemplating emigration from Syria. Before the fall of Assad’s regime, the cost of traveling from Syria to Greece was $14,000 — and an additional $10,000 to reach Germany — but now the prices have almost doubled. The journey to Greece now costs over $23,000. However, even paying such amounts, people have no guarantee: many European countries have suspended the processing of asylum applications from Syrians.

In 1962, the Ba’ath Party conducted a census aimed at identifying non-Arab populations in order to facilitate the «Arabization» of Kurdish territories in Syria. Non-Arabs were required to prove that they had been living in Syria since at least 1945. Those who could not provide such proof were classified as «foreigners» and stripped of Syrian citizenship. They were issued documents that explicitly prohibited their holders from residing in the Al-Hasakah Governorate. The government also expropriated Kurdish lands and deported the former owners. The authorities constructed free housing in these areas for ethnic Arabs and encouraged them to take up agriculture. This policy, devised by the Ba’ath Party, became known as the «Arab Belt.»

Many Kurds are still contemplating emigration from Syria. The journey to Greece now costs over $23,000

There is not yet any official agreement between HTS and the SDF, but negotiations are underway. Ahmed al-Sharaa stated that the SDF would join the new Syrian army. SDF Commander-in-Chief Mazloum Abdi agreed, but set a condition that HTS cannot fulfill on its own: the cessation of Turkish attacks in Syria.

Almost immediately after the fall of the Assad regime and the rise of HTS to power, Turkish President Erdogan declared: “We have paved the way to victory in Syria.” A Turkish delegation was the first to arrive in Damascus for an official visit. Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan demanded that the new Syrian authorities expel Kurdish groups from the country, threatening that Turkey, despite American wishes, might conduct a military operation if the demand went unheeded.

Nevertheless, there are also positive signals. For the first time in years, the Turkish authorities have allowed visitors to meet with the imprisoned leader of the PKK, Abdullah Öcalan. Western capitals are increasingly calling for Syria’s Kurds, key allies in the democratic world’s fight against ISIS, to be supported. U.S. military personnel even began building a new military base in Kobani.

However, Mazlum, speaking to The Insider, remains skeptical: “Any agreement with Turkey at this stage, on any front, will not fundamentally change the situation, but will only postpone a new occupation. We are fighting for our survival. We will not surrender soon, but victory is still far from reach.”

Without external support, the Kurds' resources are doomed to lag well behind those of the pro-Turkish proxies in Syria — and, of course, of the Turkish army itself. If Turkey openly enters the war, the outcome is predictable: a defeat for the SDF. That’s exactly why the Kurds are making diplomacy a primary focus of their efforts to live in peace.

In 1962, the Ba’ath Party conducted a census aimed at identifying non-Arab populations in order to facilitate the «Arabization» of Kurdish territories in Syria. Non-Arabs were required to prove that they had been living in Syria since at least 1945. Those who could not provide such proof were classified as «foreigners» and stripped of Syrian citizenship. They were issued documents that explicitly prohibited their holders from residing in the Al-Hasakah Governorate. The government also expropriated Kurdish lands and deported the former owners. The authorities constructed free housing in these areas for ethnic Arabs and encouraged them to take up agriculture. This policy, devised by the Ba’ath Party, became known as the «Arab Belt.»