Under pressure from the Trump administration, the UN Security Council has unequivocally sided with Morocco in its conflict with the people of Western Sahara. Likely driven by the American president’s desire to quickly chalk up another resolved conflict to his record, the decision at the UN nullifies years of effort to find a compromise and sets a dangerous precedent for any autocrat with eyes for their neighbors’ territory.

On Dec. 10, World Human Rights Day, the Working Group on Human Rights in Western Sahara published an open letter addressed primarily to UN member states. It alerted the world to the fact that thousands of Sahrawis, members of the indigenous people of the Sahara, are being subjected to systematic violence at the hands of the Moroccan authorities. The Sahrawis’ land was annexed by the neighboring monarchy half a century ago, they have no effective means to defend their rights, and the international community has largely turned a blind eye to their plight.

The Working Group on Human Rights in Western Sahara is made up of Sahrawi representatives. In their letter, they single out the negative role played by Donald Trump, noting that his 2020 decision to support Morocco’s claims to sovereignty over Western Sahara worsened the situation of the indigenous population and emboldened officials in Rabat, pushing them to commit more crimes against the autochthonous population.

The letter, however, does not mention the detail that, this past October, Trump’s position was endorsed by the UN Security Council, which adopted a resolution recognizing Morocco’s rights to Western Sahara. In its key provisions, the Security Council document mirrors the conflict settlement plan adopted by the Moroccan authorities. Both the plan and the resolution envisage granting the region formal autonomy, while leaving all decisions related to defense policy, control over natural resources, and security, in the hands of the central government.

For decades, the UN postponed a decision on Morocco’s sovereignty over Western Sahara, carefully distancing itself both from the Sahrawis demanding independence and from the Moroccan monarch, who gained control over this vast territory via highly questionable means.

From the late 19th century, Western Sahara was a Spanish colonial possession, and in the 1950s, Madrid incorporated it into the state as one of its provinces. But as decolonization was already underway, the UN was pressuring Spain to withdraw from the Sahara. Mauritania and Morocco, both bordering Spanish Sahara, joined in with each neighboring state planning to integrate the region into its own territory.

At the initiative of the UN’s leadership, the question of the region’s status was referred to the organization's International Court of Justice, which in October 1975 issued a ruling recognizing Western Sahara’s close cultural, ethnic, and economic ties to Morocco, while at the same time affirming the right of the region’s population to determine its own future through a referendum. That referendum, however, was to be put off “until the General Assembly decides on the policy to be followed in order to accelerate the decolonization process in the territory” — whatever that was meant to entail.

Just weeks after the International Court of Justice issued its opinion, Morocco’s King Hassan II called on his subjects to march peacefully into the Sahara and thereby “put an end to Spanish imperialism.” The monarch maintained that this assertion of sovereignty was not an annexation, but the restoration of Morocco’s territorial integrity, which he argued had been disrupted by European conquerors more than a century earlier.

On Nov. 6, 1975, some 350,000 Moroccans, including many women and children, crossed into Western Sahara and advanced several kilometers inland. They carried national flags and portraits of the king while chanting the demand that “the Sahara be returned to Morocco.”

The timing for a peaceful annexation was perfect: Francisco Franco, the Spanish caudillo who had ruled the country for 36 years, was gravely ill, and the political elite in Madrid was preoccupied with squabbling over his succession — no one intended to get seriously involved in a fight over a desert on a neighboring continent. Despite their overwhelming advantage in manpower and equipment, the Spanish handed over Western Sahara to Morocco and Mauritania without a fight (with Mauritania receiving the southern part of the region). The interests of the local population were ignored in the transfer, even though the Madrid Accords, which governed the handover, included a commitment to take into account the opinion of the indigenous inhabitants of the region, expressed through their representatives in the local assembly — the Djema’a.

Despite having an overwhelming advantage in manpower and equipment, Spain handed over Western Sahara to Morocco and Mauritania without a fight

By the time the Madrid Accords were signed, some locals had already been waging a low-intensity guerrilla war against the Spanish for years, fighting for the independence of the Sahrawi lands. The largest of these guerrilla groups was the Polisario Front, which carried out attacks on remote Spanish garrisons and seized weapons from army and police depots. Though small in number — only a few hundred fighters when the Spanish withdrew — the guerrilla units were supported by Algeria, which borders Western Sahara and also sought to claim part of the region. Polisario fighters attempted to take control of the southern settlements as they were being abandoned by the Spanish, but within just a few days they suffered defeat at the hands of the Mauritanian army.

And that was only the beginning of the often bloody chaos that would engulf Western Sahara for years to come. Late-1970s U.S. intelligence reports indicate other players, including Libya, Benin, the USSR, and even North Korea, attempted to influence the situation in the region. In effect, Western Sahara became one of the most brutal fronts of the Cold War, albeit a relatively obscure one.

Morocco received financial, military, and diplomatic support from the U.S. and Western Europe, primarily France, while the Polisario Front gained the backing of the socialist bloc. Before the collapse of the USSR, the Front even joined the Socialist International, where it remains a consultative member to this day. Its main achievement, however, was the proclamation of the independent Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), claiming all 266,000 square kilometers of Western Sahara.

To justify its legitimacy, SADR leadership pointed to the fact that the declaration of independence was supported by the majority of deputies in the local parliament, convened at the height of Spanish rule. As noted earlier, the Madrid Accords obliged the parties to respect the position of the Sahrawi parliamentarians, and from the SADR government’s perspective, the new republic was the legal successor to the Spanish administration (it was even proclaimed the day after Madrid formally ended its sovereignty over Western Sahara). Morocco and Mauritania, they argued, were occupying states that had illegally invaded foreign territory and were imposing their own order by force.

Today, the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic is a fully autonomous entity, recognized by nearly 50 countries, including South Africa, Peru, and Mexico. At the same time, the SADR has never controlled the entire territory of Western Sahara — or even most of it. The partially recognized republic maintains control over several southeastern districts of the region, most of which were occupied by the Mauritanian army after 1975. For Mauritania, occupying even part of Western Sahara proved to be an overwhelming burden. Sahrawi guerrillas constantly harassed Mauritanian convoys and garrisons, launching sudden attacks and immediately retreating into the desert, which they navigated masterfully.

The small Mauritanian army suffered losses it could not afford to take, and even intervention by the French Air Force failed to help. Recognizing that it could no longer keep fighting, Mauritania renounced all claims to Western Sahara in 1979 and withdrew from the occupied territories — some of which were immediately taken over by the Moroccan army, and others by the Polisario Front.

Although Morocco had a far more capable army than Mauritania, it too suffered losses in the guerrilla war. By the 1980s, Rabat had gradually shifted from the position of “no concessions” to a willingness to at least try to negotiate. All the more so because the UN, the main international arbitrator, had insisted since the time of Spanish rule on the Sahrawis’ right to self-determination through a referendum.

It was largely the UN’s refusal to recognize Morocco’s annexation of Western Sahara without clear, vote-backed consent from the local population that helped legitimize the SADR. The partially recognized republic was even admitted to the Organization of African Unity (OAU), which was later reformed as the African Union.

In 1988, the OAU and the UN adopted a resolution calling for a referendum in Western Sahara, giving the people the right to determine their own future. A few years later, a full UN mission was established to organize and oversee the vote. From the very beginning, however, the mission faced seemingly insurmountable challenges.

Most importantly, Rabat was categorically opposed to any mention of Western Sahara’s independence on the ballot and was only willing to offer various forms of regional autonomy in the plebiscite. The Sahrawis, however, insisted that the referendum include the option of full independence. They also demanded that only indigenous inhabitants of Western Sahara be allowed to vote, while Moroccan settlers, who by the 1990s outnumbered the natives, should have no voting rights.

At the same time, the SADR government was willing to grant its citizenship to the settlers and their descendants. In addition, contentious issues included organizing voting in Sahrawi refugee camps in Algeria and in territories not controlled by the Moroccan authorities. The parties and mediators became bogged down in endless negotiations, reconciliations, and clarifications of positions. The referendum was never held.

At an impasse, in 2007 the Moroccan authorities adopted the so-called autonomy plan, which was aimed at the fastest and most complete integration of Western Sahara under their control. The stated intention was for the people of Western Sahara to “manage their own local affairs, with the necessary safeguards, and without prejudice to the sovereignty prerogatives of the Kingdom of Morocco and its territorial integrity.” Their languages and culture would be protected at the state level, and elected executive and legislative bodies would be established to handle the region’s internal affairs.

Despite support from some Western states, the blueprint was immediately rejected by the SADR as disregarding Sahrawi rights while legitimizing the occupation. The UN described it as a “serious and credible Moroccan effort” but did not disband the mission still in place preparing for the referendum.

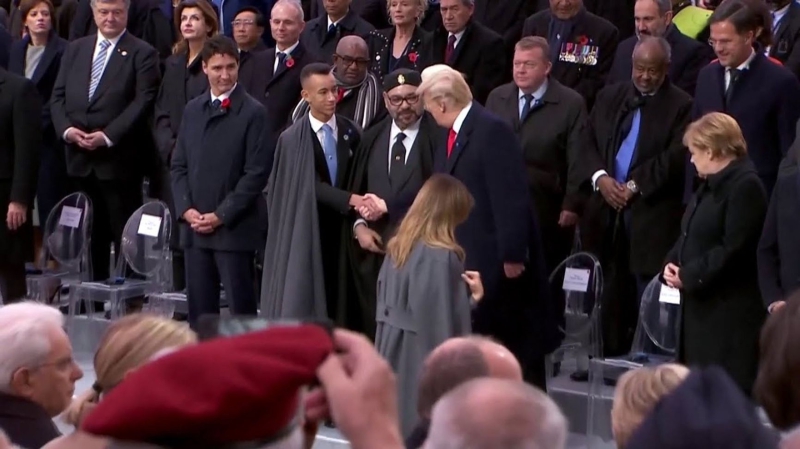

Meanwhile, the status of Western Sahara remained highly uncertain: officially, no country in the world recognized Morocco’s sovereignty over the territory, and the conflict remained in limbo until the arrival of Donald Trump’s first administration. In 2020, Washington decided to unequivocally side with Rabat.

“Now, therefore, I, Donald J. Trump, President of the United States of America, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and the laws of the United States, do hereby proclaim that, the United States recognizes that the entire Western Sahara territory is part of the Kingdom of Morocco,” read the White House’s official statement, written in Trump’s unmistakable style.

Interestingly, at the time, both the UN leadership and respected international experts almost unanimously predicted that Washington's position would not affect how other countries or supranational organizations viewed the conflict, as the question of Western Sahara’s status was far too complex and sensitive to be resolved so definitively. Yet five years later, in October 2025, under pressure from Trump Administration 2.0, the UN Security Council adopted (with no votes against) a resolution endorsing Morocco’s autonomy plan, one that cements Western Sahara as part of Morocco and makes no mention whatsoever of the region's potential statehood.

Arguments in favor of Morocco’s plan boil down to the following: Morocco has long administered 80% of Western Sahara and generally manages the region effectively; around two-thirds of the territory’s population (primarily settlers and their descendants) identify as Moroccan and do not wish to change the status quo; and the Polisario Front simply does not, and for the foreseeable future will not, have a realistic chance of establishing a stable sovereign state over the entire territory it claims.

It was precisely these arguments that the Security Council endorsed, despite their ambiguity. Some observers even rushed to claim that by supporting the resolution, the UN had betrayed its decolonization mission — one of its core responsibilities — and that the Security Council had sided with the stronger party, abandoning the role for which it was originally established.

The UN Security Council abandoned international arbitration and sided with the stronger party

In addition, some are concerned that the arguments used by Morocco and its allies to justify its claim over Western Sahara could be used to legitimize annexations elsewhere. After all, if Morocco can claim thousands of square kilometers of territory merely on the basis of having administered them for a long time and because the settlers wish to maintain the status quo, what would prevent Israel from legalizing its settlements in the West Bank, which are still considered illegal under international law? The same question applies to the occupied Syrian territories.

How is the annexation of Western Sahara — accompanied by the mass exodus of the indigenous population and an even larger influx of settlers — fundamentally different from the seizure of Ukraine’s Crimea? There, the occupiers are forcibly replacing the population, bringing in tens of thousands of Russians and creating increasingly unbearable conditions for Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians.

And would the United Arab Emirates then have the right to demand recognition of its sovereignty over Yemen’s Socotra Island if it decided to maintain a long-term military presence there while expelling locals dissatisfied with the foreign occupation and replacing them with a loyal population?

In fact, it was precisely the fear of creating a perilous international precedent that kept the UN from taking a definitive position on Western Sahara’s status for a full 50 years. Now, however, Donald Trump is undermining the foundations of international law and weakening already fragile international institutions.