Not long ago, Russia was considered a key player in the Middle East. Moscow had managed to maintain good relations with Syria, Iran, and Israel, leveraging its status as a broker capable of talking to both sides in a range of disputes. Today, however, the long-planned Russia-Arab summit in Moscow has been postponed indefinitely, and instead of welcoming a Syrian ally for a visit to the Kremlin earlier this month, Putin met with the new president, Ahmed al-Sharaa. Still, despite losing some of its sway, Russia has not given up on its ambitions to remain a player in the region.

Vladimir Putin postponed the first Russia-Arab summit, scheduled for Oct. 15, just five days before the event. No new date has been announced for the gathering, which had been in the works since December 2024. Moscow hopes to hold the summit in November, but most potential guests remain noncommittal.

There are two potential causes for the summit’s cancellation. The official version was announced by Putin himself on Oct. 10: “We agreed to postpone our meeting — Russia and the League of Arab States. This was my initiative, as I would hate to interfere with the [Gaza ceasefire] process that, as we hope, has now stabilized and is moving forward, by the way, on the initiative and with the direct involvement of Trump in the Middle East.”

Putin’s statement came as a surprise, especially as it came one day after Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov had given an interview on the topic of the planned summit. According to Lavrov, Moscow understands that many Arab countries are currently concerned with the Palestinian issue and are participating in relevant consultations. “But we have reason to believe that the vast majority of the League of Arab States’ members would participate [in the summit] at the highest level,” he emphasized on Oct. 9.

Hence the question: what changed in a day or two, compelling Moscow to cancel one of the year’s key events? Bloomberg reported that the summit may have been canceled because, as of Oct. 6–7, an insufficient number of Arab leaders had confirmed their participation. Notably, key figures such as Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, UAE President Mohammed bin Zayed, and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi all planned to be absent.

Putin’s cancellation came one day after Foreign Minister Lavrov gave an interview promoting the summit

Bloomberg suggests that the hesitation of Arab leaders over whether to attend the Moscow summit may have been driven by concerns over potential new U.S. sanctions against Russia, as well as by the U.S. administration’s general dissatisfaction with Putin’s intransigence regarding the end of the war in Ukraine. In contrast, Trump is very pleased with his Arab allies, especially now that the situation around Gaza and the hostages has finally begun to move forward.

In recent weeks, events in the Middle East have unfolded rapidly. On Sept. 29, President Trump, in the presence of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, presented his 20-point plan for a ceasefire in the Gaza Strip. Standing beside Trump, Netanyahu announced that he agreed with the U.S. president’s proposals.

A few days later, Hamas also said “yes,” albeit with numerous reservations. However, this “yes” was enough for Trump. Israel and Hamas, along with a group of mediators that included Egypt, Qatar, Turkey, and the U.S., began discussing the details of the first stage of the plan: the terms of an exchange that would bring home Israeli hostages and Palestinian prisoners. This process took several more days, but a hard-won compromise was eventually reached. On the night of Oct. 10-11, it was announced that the Israeli government had approved the deal with Hamas, and the ceasefire agreement went into effect.

The return of the Israeli hostages was scheduled for Monday, Oct. 13, and it quickly became clear that Trump planned to fly to the Middle East for the occasion. That day, he addressed the Israeli Knesset in Jerusalem, and it appeared as if a plan were in place to travel on to Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, where a hastily arranged international “peace summit” would designate the U.S., Egypt, Qatar, and Turkey as guarantors of the ceasefire.

And then it turned out that there was a scheduling conflict: the foreign ministers of the League of Arab States (LAS) were slated to arrive in Moscow on Oct. 13 to finalize the documents for the Russia-Arab summit. However, after the announcement of the summit in Sharm El Sheikh, it became clear that many foreign ministers would opt for the Trump meeting. As a result, the Kremlin chose to put its summit on hold.

A few more nuances deserve attention. Mohammed bin Salman and Mohammed bin Zayed did not travel to Sharm El Sheikh. Saudi Arabia was represented at the “peace summit” by its foreign minister, and the UAE by its vice president. Officially, both countries supported Trump’s plan. However, according to Arab sources, they were very unhappy that Hamas would be allowed to retain a presence in Gaza as a result of the deal, even if it were formally removed from power.

Regional rivalries are also an important factor. The UAE had repeatedly proposed ideas similar to Trump’s plan, while Saudi Arabia, together with France, actively promoted a proposal to recognize the State of Palestine and drafted a strategy for its development. Yet in the end, the laurels of peacemakers went to others. However, traveling to Moscow while ignoring the Egyptian “peace summit” would have been an unmistakable challenge to Washington. Quarreling with Trump was not a desirable course for Riyadh or Abu Dhabi plans — not because they fear his wrath, but simply because no one wants unnecessary friction at this moment.

To avoid an open confrontation with Trump, Putin chose not to interfere with the U.S. president’s triumph as a peacemaker

As it turned out, Putin does not want an open confrontation with Trump either. In the end, he chose not to interfere with the U.S. president’s triumph as a peacemaker. Moreover, Moscow realized that even a large-scale event was bound to be overshadowed by the developments in Gaza and could hardly position Moscow as an alternative to Washington (Russian officials have repeatedly criticized Washington’s policies as the source of the problems in the region). Against the backdrop of the release of the Israeli hostages, such a move would have been out of place and would have looked pitiful — especially considering Putin was not invited to Sharm El Sheikh.

Moscow understands, just as Arab countries and Israel do, that Trump’s plan might not survive contact with reality on the ground, as seemingly every element except the return of the hostages breeds new disputes among the conflicting parties. Even the exchange itself was not without difficulties: Hamas returned 20 remaining living hostages to Israel, but has been dragging out the repatriation of the bodies of the deceased. Under the circumstances, Russia has no choice but to wait: let Trump enjoy his triumph, and let the status quo from a few weeks back make its return.

As for the concerns of Arab countries regarding Trump’s promises to tighten sanctions on Russia (as Bloomberg reported), everyone understands how unpredictable the American president’s moods can be. First came the threats, and then a phone call between the U.S. and Russian presidents. A new meeting between the two leaders is already being planned in Budapest (though the odds of it actually taking place are no better than those of the Russia-Arab summit).

The conversation between Putin and Trump was arranged on Thursday, Oct. 16, a day before Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky visited Washington. However, Putin began by congratulating Trump on his success in stabilizing the situation in the Gaza Strip. Moscow is known for understanding the mindset of the American president, and flattering him costs Putin nothing.

In truth, however, Putin is no less skeptical toward Trump’s plan than the regional players are. But the problem for Moscow is: Russia has nothing to bring to the table and has to follow the lead of the Arab countries in matters of Middle East settlement.

The idea of the Russia-Arab summit was first proposed last December in Marrakesh, Morocco, at the sixth meeting between Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and his counterparts from the countries of the League of Arab States. Such meetings have been held every other year for the past 12 years or so, ever since Moscow made its return to the region.

The start of the Russian Aerospace Forces’ campaign in Syria in 2015 made Moscow a serious player in the Middle East for the first time since the collapse of the Soviet Union. As a result, a number of Middle Eastern and African countries have leveraged ties with Russia as a political and military counterbalance to the West.

The first shifts in the opposite direction began after Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, shifting significant military resources — and even more of its critical attention — out of the Middle East. In this new reality, Moscow became somewhat dependent on the Arab capitals — for diplomatic support. Rather than condemning Russia’s aggression outright, most took an explicitly neutral stance — this at a time when much of the world was coming out on Kyiv’s side. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar repeatedly acted as intermediaries between Moscow and Kyiv in resolving humanitarian issues, such as prisoner exchanges. Also of note is the fact that the first Russian-American contacts after a long hiatus took place in Saudi Arabia.

Russia has become dependent on Arab countries, which have taken an explicitly neutral stance between Moscow and Kyiv

Crucially, the Arab monarchies have not abandoned economic cooperation with Russia, despite the challenges posed by U.S. sanctions. They are aware of Trump's reluctance to spoil relations with the Arab world, knowing how much he values American investments and business ties in the region.

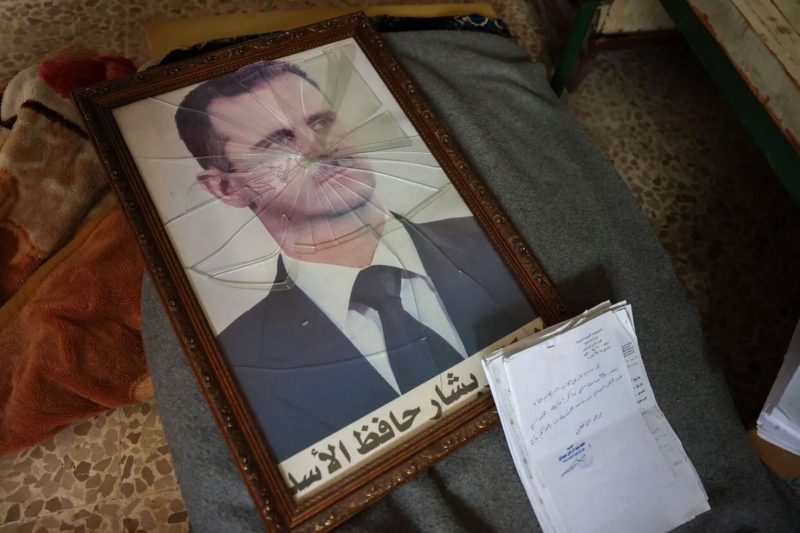

However, at the end of 2024, things seemed to have taken a drastic turn. Many predicted that with the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Damascus, Russia would lose not only Syria but the entire Middle East. The reality turned out to be somewhat different.

The concept of the first Russia-Arab summit emerged roughly two weeks after Assad fled to Moscow. Russia’s proposal had been prepared ahead of Lavrov’s trip to Marrakesh, with the aim of proving to the West that Russia was not, in fact, isolated — that many countries still wanted to cooperate with it despite the ongoing war in Ukraine. After the overthrow of Assad’s regime, the political significance of the Russia–League of Arab States summit for Moscow only increased, as the Kremlin now had to demonstrate that it still played a significant role in the Middle East.

The summit was expected to address both economic cooperation and political issues. Foremost among these was the war in the Gaza Strip, which had affected nearly all countries in the region. Another political topic was the creation of an alternative alliance to NATO. While Moscow had previously focused on preventing NATO’s expansion into Eastern Europe, it is now attempting to counter Western influence further east.

“NATO now says that its task is to ensure the security of its member states’ territories, and that threats currently come from the South China Sea. They said as much. They are now actively deploying their infrastructure to the eastern edge of Eurasia,” Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov stated in his Oct. 9 interview. According to the foreign minister, Putin is promoting an alternative to European security — the concept of a “Greater Eurasian Partnership as a material foundation for building a continent-wide security architecture.”

Russia needs to place the summit in the spotlight of the international community — or not hold it at all

However, all these discussions will have to be put on hold. Whether the Russia-Arab summit will ultimately take place depends on developments in the Middle East, and also on the relationship between Moscow and Washington. Russia needs to place the summit in the spotlight of the international community — or not hold it at all. For now though, Moscow has found a different way to demonstrate its good standing in the region.

One of the highlights of the Moscow summit was supposed to be the visit of Syria’s interim president, Ahmed al-Sharaa. Russia was very anxious about his attendance and repeatedly stated that it eagerly awaited the new Syrian leader. Al-Sharaa’s visit took place despite the summit’s cancellation — and even appeared far more significant as a standalone event.

Just a year ago, a meeting between al-Sharaa and Putin would have been unthinkable. Al-Sharaa, until recently known as Abu Mohammad al-Julani, led the group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which is listed as a terrorist organization by the UN and several countries, including the U.S. and Russia. During the Syrian Civil War, Russian Aerospace Forces (VKS) regularly struck HTS positions in Idlib. Therefore, it seemed natural that after HTS and its affiliated groups seized power in Syria last December, Russia’s presence on Syrian territory would come to an end.

Western capitals persistently urged al-Sharaa to close Russia’s military bases in his country, offering financial incentives and support. But the new Syrian leader decided not to put all his eggs in one basket. Contacts with Moscow continued. In his interviews, al-Sharaa repeatedly emphasized that the new Syria intends to develop cooperation with all countries willing to support it — Russia included.

In Moscow, Ahmed al-Sharaa was received with the highest honors. The Saudi outlet Asharq Al-Awsat notes that his talks with Putin took place in the most luxurious hall — the Green Drawing Room of the Grand Kremlin Palace. Intriguingly, Assad and many of his high-ranking military associates had taken refuge in Moscow after HTS and their allies entered Damascus. Initially, al-Sharaa had loudly declared that he would demand the extradition of Assad and the other “criminals” — and even had a warrant for the arrest of the former Syrian president issued by a Damascus court just before his departure to Moscow.

However, under the spotlight at the start of the talks, Putin and al-Sharaa were very cautious, avoiding sensitive topics and signaling a willingness to cooperate. Putin emphasized that relations between Damascus and Moscow are not tied to “political expediency or special interests.”

“Throughout all these decades, we have always been guided by one thing — the interests of the Syrian people,” Putin said. In other words, regardless of who sits in the presidential palace in Damascus, Russia wants to maintain its presence in Syria.

For his part, al-Sharaa also mentioned the historical ties between the countries. “We will try to reboot the full range of our relations and introduce you, among others, to the new Syria,” he emphasized at the start of the talks. Everything else remained behind the scenes, although the parties undoubtedly touched on the fate of Assad, the future of Russia’s military bases in Syria, and previously voiced demands from Damascus for compensation from Moscow for the destruction caused during the years of the Syrian conflict.

Apparently, as noted by Asharq Al-Awsat, the future of Russia’s bases in Syria still requires further discussion at the technical, political, and military levels. Some Syrian sources indicate the existence of a preliminary agreement on the joint management of the Khmeimim airbase and the reopening of the nearby Latakia airport.

As Syrian Foreign Minister Asaad al-Shaibani stated to Syrian News Channel on Saturday, relations between Moscow and Damascus are progressing, but “no new agreements have been signed” so far. Al-Shaibani also added that “the agreements concluded with the previous regime have been suspended.”

The day before, Ashhad Salibi, Deputy Director of the Department for Russia and Eastern Europe at the Syrian Foreign Ministry, stated in an interview with the same channel that the Moscow talks addressed potential new legal mechanisms for cooperation (in particular, regarding the search for wanted individuals) as well as support for Syria’s position in international forums. He also emphasized the importance of further coordination in the Security Council and other UN bodies to strengthen Syria’s presence and back its strategic interests. In addition, the diplomat noted that during the meeting with Putin, al-Sharaa demanded the extradition of the “fugitive Bashar al-Assad.”

However, Moscow has long made it clear that this will not happen. Following the talks, Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov stated he had nothing to add regarding Assad’s extradition. It is therefore unlikely that al-Sharaa spent much time on this issue with Putin behind closed doors. Assad and his entourage are a trump card in Moscow’s hand — just as the retention of Russian military bases in Syria is a trump card for Damascus.

Assad and his entourage are a trump card for Moscow, while the retention of Russian military bases in Syria is a trump card for Damascus

At the same time, according to various Arab publications, al-Sharaa may be interested in Russia mediating disputes between Damascus and the Kurds of northeastern Syria, as well as the Druze in the south. The young regime faces many contentious issues, and the very existence of these reports suggests that Moscow’s role could still be significant for the new Syrian authorities.

Actors in the region are also discussing the possible return of the Russian military police to the Golan Heights. Interestingly, after al-Sharaa departed Moscow, Asharq Al-Awsat reported that Syrian Foreign Minister Asaad al-Shaibani and Defense Minister Murhaf Abu Qasra remained in the Russian capital.

Experts do not rule out the possibility that Moscow and Damascus could agree on mechanisms for restructuring and preparing the Syrian army, and possibly equipping it with air defense systems. This was, in particular, discussed during the visit of the Syrian Chief of Staff to Moscow a week before the high-level talks. However, this issue requires coordination of regional positions, especially between Russia and Israel.

As for the possibility of al-Sharaa’s Syria receiving compensation from Russia, the Kremlin has signaled a preliminary willingness to relieve Syria of outstanding debts and to take an active role in rebuilding the country’s damaged infrastructure. Russian Vice Prime Minister Alexander Novak told journalists immediately after the high-level meeting that Russian companies are interested in returning to Syria without delay.

In short, Moscow can no longer dictate to Damascus, but Russia’s presence is still of use to the Syrian authorities. (It should be noted that Russia’s military and political presence in Syria is also beneficial to Israel, to some extent, as it serves as a counterbalance to Turkey’s growing influence on Syrian territory.)

The “Syrian model” can also be applied more broadly to Moscow’s overall position in the Middle East. Undoubtedly, the Kremlin’s influence is limited due to the Western boycott. It has never had a fighting chance to affect the Arab-Israeli conflict, and its contacts with Iran — once an asset in relations with both the Arab world and Washington — now raise questions. As a result, Moscow and Tehran alternate between cooperation and trading barbs with each other.

However, Russia remains an actor in the Middle East, albeit one that mostly stays behind the scenes. Still, it is in a position to step onto the stage as needed. At the very least, neither the Arab countries nor Israel has written Russia off, even if their main focus is on Trump, as unpredictable as the American president may be. Under the circumstances, Moscow actually appears to be a more reliable negotiating partner.