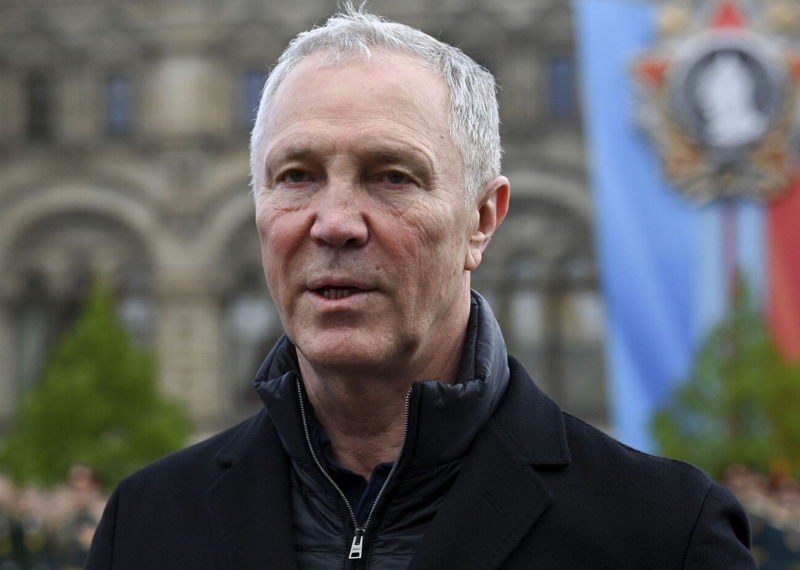

Volodymyr Mykolaienko immediately after returning from captivity. Telegram channel of Kherson Oblast Military Administration Head Yaroslav Shanko

Former Kherson mayor Volodymyr Mykolaienko returned to Ukraine on Aug. 24, 2025, after spending nearly three and a half years in Russian captivity. After Russia’s seizure of Kherson in March 2022, occupation authorities offered Nikolaenko and fellow former mayor Vladimir Saldo the opportunity to cooperate with Moscow’s forces. But while Saldo agreed — becoming the head of the occupation administration — Mykolaienko firmly refused. As a result, he was ultimately lured from his home under false pretenses and taken “to the basement.” From there, Mykolaienko ended up in a penal colony in Voronezh and later in Pakino, in Russia’s Vladimir Region. In an interview with The Insider, the former Kherson mayor described how he was pressured to cooperate, how he and other prisoners chewed nettles to get at least some vitamins, and how young men went mad in prison, unable to withstand torture.

For me, the war began, like for everyone else, predictably. As they say, “you could smell war in the air.” But frankly, we did not believe it would be like this, that the Russians would come from all sides — from Belarus, from Crimea, and from their own border. I thought they would come from the east and try to take our lands in the Donbas, the Luhansk and Donetsk regions. But Belarus, unfortunately, let them through, and we ended up with a front line thousands of kilometers long.

They reached Kherson literally within a few hours, and the city was not ready to repel them even though our high-ranking officials, the military, and the Security Service of Ukraine reported to the president that everything was under control here and the enemy would not pass. But the opposite happened. I do not think they were particularly interested in the city itself; they were heading toward Mykolaiv and Odesa. It was there — on the border between Kherson and Mykolaiv regions — that they were stopped, and they began entering the suburbs and then the city itself.

The word stems from the Russian name for the oseledets hairstyle, “khokhol” (Russian: хохол), and is commonly used as an ethnic slur for a Ukrainian. Oseledets is a Mohawk-type haircut that features a long lock of hair sprouting from the top or the front of an otherwise closely shaven head. The word comes from the Proto-Slavic “xoxolъ” (lit. ”crest,” “tuft”).

“Victory Day” is a Soviet song written in 1975 to mark the 30th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II.

Volodymyr Saldo, head of the occupation administration of Kherson Region. Formerly a Ukrainian politician, People’s Deputy of Ukraine (2012–2014), three-time elected Mayor of Kherson (2002–2012), predecessor of Mykolaienko in this post.

Kherson residents tried to resist from the first days. Even teenagers went out to defend the city. That prevented the Russians from entering immediately. And when they finally broke through, they were shown that nobody here had been waiting for them. People went out to rallies — tens of thousands with Ukrainian flags, in national dress. The Russians did not expect that. They had been told they would be greeted with bread and salt, given flowers.

The word stems from the Russian name for the oseledets hairstyle, “khokhol” (Russian: хохол), and is commonly used as an ethnic slur for a Ukrainian. Oseledets is a Mohawk-type haircut that features a long lock of hair sprouting from the top or the front of an otherwise closely shaven head. The word comes from the Proto-Slavic “xoxolъ” (lit. ”crest,” “tuft”).

“Victory Day” is a Soviet song written in 1975 to mark the 30th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II.

Volodymyr Saldo, head of the occupation administration of Kherson Region. Formerly a Ukrainian politician, People’s Deputy of Ukraine (2012–2014), three-time elected Mayor of Kherson (2002–2012), predecessor of Mykolaienko in this post.

That is why a huge number of torture sites appeared in Kherson — to punish the disobedient, to ensure there was not even a hint of resistance. Those who went to rallies were seized and thrown into these torture chambers. After a few days they were released, but with an “escort” — so that they would not even think about disobeying the so-called new authorities.

I am proud that I stood with the citizens of our city. These were actions that from the first days showed the whole country how many Kherson residents came out in resistance. We marched in a powerful column almost across the entire city — from the central square to Park Slavy (lit. “Park of Glory”). And I am proud that I walked at the head of this column next to a huge Ukrainian flag that people made themselves.

The word stems from the Russian name for the oseledets hairstyle, “khokhol” (Russian: хохол), and is commonly used as an ethnic slur for a Ukrainian. Oseledets is a Mohawk-type haircut that features a long lock of hair sprouting from the top or the front of an otherwise closely shaven head. The word comes from the Proto-Slavic “xoxolъ” (lit. ”crest,” “tuft”).

“Victory Day” is a Soviet song written in 1975 to mark the 30th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II.

Volodymyr Saldo, head of the occupation administration of Kherson Region. Formerly a Ukrainian politician, People’s Deputy of Ukraine (2012–2014), three-time elected Mayor of Kherson (2002–2012), predecessor of Mykolaienko in this post.

We all chanted where the Russian warship should go. After that, they started firing on these demonstrations: they fired [their weapons] into the air, threw gas, smoke and stun grenades, and dragged away the most active participants to intimidate the rest.

On the very first day of the Russian army’s advance into the Kherson Region, I joined the territorial defense. They even wrote it like that in the first interrogation: “He maximally interfered with the entry of Russian troops into the city of Kherson.”

The word stems from the Russian name for the oseledets hairstyle, “khokhol” (Russian: хохол), and is commonly used as an ethnic slur for a Ukrainian. Oseledets is a Mohawk-type haircut that features a long lock of hair sprouting from the top or the front of an otherwise closely shaven head. The word comes from the Proto-Slavic “xoxolъ” (lit. ”crest,” “tuft”).

“Victory Day” is a Soviet song written in 1975 to mark the 30th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II.

Volodymyr Saldo, head of the occupation administration of Kherson Region. Formerly a Ukrainian politician, People’s Deputy of Ukraine (2012–2014), three-time elected Mayor of Kherson (2002–2012), predecessor of Mykolaienko in this post.

They brought me to the basement of the regional police department, which had not been used for many years. There were terrifying cells — cold, damp, filthy, with water dripping. Less than an hour later, they took me in for interrogation. They believed I had stayed in Kherson as the leader of the resistance. They thought, “If he’s a former mayor, then he must be the head of the underground.”

The questions were: “Where are the weapons depots? Who else leads the resistance?” I tried to explain that I was an ordinary member of the territorial defense and had nothing to do with military matters, but they did not believe me. They beat information out of you — they have no other methods.

The word stems from the Russian name for the oseledets hairstyle, “khokhol” (Russian: хохол), and is commonly used as an ethnic slur for a Ukrainian. Oseledets is a Mohawk-type haircut that features a long lock of hair sprouting from the top or the front of an otherwise closely shaven head. The word comes from the Proto-Slavic “xoxolъ” (lit. ”crest,” “tuft”).

“Victory Day” is a Soviet song written in 1975 to mark the 30th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II.

Volodymyr Saldo, head of the occupation administration of Kherson Region. Formerly a Ukrainian politician, People’s Deputy of Ukraine (2012–2014), three-time elected Mayor of Kherson (2002–2012), predecessor of Mykolaienko in this post.

They beat me either with their fists or with rubber batons. On Good Friday they beat me twice and broke my ribs. But I was lucky: I was among the first high-profile detainees, and FSB officers worked with me, and they did not get their hands too dirty. They had one executioner who constantly beat everyone.

After the beating, they “talk” to you. If you do not say something, they “talk” again, but with a rubber baton, then another interrogation, and so on in a circle. When I came back, people told me that in Kherson they organized torture chambers even for children — for teenagers who went out to defend the city. There were absolutely horrific things, so terrible that you do not even want to talk about them. So I really was lucky, even though they beat me more than ever in my life.

After a couple of days, when other detainees confirmed that I was an ordinary member of the territorial defense, offers of cooperation began. They said: “Choose any position you want, whatever you consider acceptable, and work. On one side — a position, safety, and money, on the other — a pit.”

I chose the pit.

On the first day at the police department, I was kept in solitary confinement. Then I spent about a day in a cell with a guy from the territorial defense, a former police officer. After that, we were placed with a third person: my company commander was brought in. It was frightening to look at him. From below the waist to the tips of his toes, it was all one big, nasty bruise. The man was simply black and blue — that's how badly he had been beaten.

Now imagine this: for the day, they gave us one soldiers’ ration — one for three people. And even from that they took out anything tastier for themselves, chocolate bars and the like. They gave us a third of what was left — just enough to keep us alive. But that wasn’t the worst part. We endured the lack of food, but the interrogations were much worse.

The word stems from the Russian name for the oseledets hairstyle, “khokhol” (Russian: хохол), and is commonly used as an ethnic slur for a Ukrainian. Oseledets is a Mohawk-type haircut that features a long lock of hair sprouting from the top or the front of an otherwise closely shaven head. The word comes from the Proto-Slavic “xoxolъ” (lit. ”crest,” “tuft”).

“Victory Day” is a Soviet song written in 1975 to mark the 30th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II.

Volodymyr Saldo, head of the occupation administration of Kherson Region. Formerly a Ukrainian politician, People’s Deputy of Ukraine (2012–2014), three-time elected Mayor of Kherson (2002–2012), predecessor of Mykolaienko in this post.

They held us for about 10 days. I was there for 10 days, some a little longer, some less. Then, on May 2, they took us to Sevastopol. When we arrived there, they met us, stripped us, and were surprised: “Listen, what happened to you?” They didn’t even touch us — we were all covered in bruises, completely blue. We replied that we had all fallen together by accident, and they pretended to believe us.

The word stems from the Russian name for the oseledets hairstyle, “khokhol” (Russian: хохол), and is commonly used as an ethnic slur for a Ukrainian. Oseledets is a Mohawk-type haircut that features a long lock of hair sprouting from the top or the front of an otherwise closely shaven head. The word comes from the Proto-Slavic “xoxolъ” (lit. ”crest,” “tuft”).

“Victory Day” is a Soviet song written in 1975 to mark the 30th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II.

Volodymyr Saldo, head of the occupation administration of Kherson Region. Formerly a Ukrainian politician, People’s Deputy of Ukraine (2012–2014), three-time elected Mayor of Kherson (2002–2012), predecessor of Mykolaienko in this post.

When they asked what happened to us, we replied that we had all fallen together by accident, and they pretended to believe us

In Sevastopol they kept us for two days. It was some kind of exhibition site, where [Russia’s human rights ombudswoman Tatiana] Moskalkova liked to come and show her journalists how “well” Ukrainian prisoners were treated. There they did not beat us. They fed us well. There was even a television and board games — chess, checkers — but it was all just for show.

On May 4, 2022, we were transferred from Sevastopol to the Voronezh Region, and five months later to the Vladimir Region. When we arrived in Voronezh, they beat us everywhere — first right there at the airfield after being flown in, and then at intake. Before seeing a doctor, my nose was already crooked. I was standing there, blood running. He looked at me: “What happened to you?” What could I say? — “I fell.” The only question was: “Can you breathe?” I said: “Well, I think so.” That was the doctor’s examination.

After that came intake, and they started running us through a gauntlet. Guards with rubber batons stood there, and they led you through, and everyone beat you. This was done to intimidate you, to make you understand that you had fallen into such “brotherly embraces” that you should not even think about resisting. So that you would feel like a worm with nowhere to hide. If you even just breathed in their direction, they immediately beat you.

The routine in both places was almost the same. At 6 a.m. we got up, and they immediately turned on the radio — very loudly, so that we could not talk to each other. There were propaganda programs, Putin saying we were one people and anyone who disagreed should die. Or some Moscow priests talking about how great it is to be Russian. There was a lot of Russian “Orthodox” propaganda. I would put it this way: there’s a lot of Russianness there, but practically no Orthodoxy. Because the person who turns on programs about Jesus Christ for you in the morning can beat you half to death in the evening for being Ukrainian and not agreeing to be part of this “one people.” This propaganda continued until 10 p.m. — until “lights out.”

Bright lights were on constantly, they never turned off, day or night. Almost all of us lost our eyesight because of the artificial lighting, which was blinding.

There were inspections — morning and evening. It looked like this: we stripped down to our underwear — in summer and winter — for inspection. In the Vladimir region, they might not beat you during inspections. In Voronezh — they beat you every time. These were the first months of the war: they took you out, and they beat you. As a preventive measure, they might beat us harder, they might beat us less severely, but they always beat us.

The word stems from the Russian name for the oseledets hairstyle, “khokhol” (Russian: хохол), and is commonly used as an ethnic slur for a Ukrainian. Oseledets is a Mohawk-type haircut that features a long lock of hair sprouting from the top or the front of an otherwise closely shaven head. The word comes from the Proto-Slavic “xoxolъ” (lit. ”crest,” “tuft”).

“Victory Day” is a Soviet song written in 1975 to mark the 30th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II.

Volodymyr Saldo, head of the occupation administration of Kherson Region. Formerly a Ukrainian politician, People’s Deputy of Ukraine (2012–2014), three-time elected Mayor of Kherson (2002–2012), predecessor of Mykolaienko in this post.

As a preventive measure, they might beat us harder, they might beat us less severely, but they always beat us

In Voronezh they liked to do this: we stood with our legs spread wide, arms spread and pressed against the wall, and when your hands were on the wall, they took a rubber baton and hit your arm. Then they gave you food, and you could not eat because your arm did not work. Or: “Give me your foot” — and they hit your heel so that you could not step on it.

There was one guy who clearly enjoyed it. He had a wooden mallet. He constantly hit me on the head with this wooden hammer. Or with a stun gun — all over my back, until my skin smelled like burned meat. I had the feeling that he got some kind of sexual pleasure from it. These people know very well what pain is and can turn anything into pain. They beat my legs so badly that the bruises still have not gone away.

The worst beatings happened on the upper floors. You could hear the guys screaming upstairs as they were beaten. And expecting the beating is worse than the beating itself. You think: just get it over with already.

One evening they took me out. I had said something wrong to the guard, and they decided to punish me. They took me to the upper floor, to a room without cameras. On the way they asked, “How old are you?” I was 63. They said, “We wanted to test a new device on you, but we won’t.” They just beat me. Then they said, “Maybe you want a cigarette?” — “No, I don’t smoke.” — “All right.” And they added: “Next time we’ll definitely hang you up and test new devices on you. You’ll hang like Buratino in the fairy tale.”

Sometimes they took us out for a walk, or to the bathhouse — usually once a week. In Voronezh the bathhouse itself was more or less normal. But getting there was hell. You run from one building to another, and they either keep beating you or set the dogs on you. While you go down from your floor, on every floor they beat you. And on the way back it’s the same.

The word stems from the Russian name for the oseledets hairstyle, “khokhol” (Russian: хохол), and is commonly used as an ethnic slur for a Ukrainian. Oseledets is a Mohawk-type haircut that features a long lock of hair sprouting from the top or the front of an otherwise closely shaven head. The word comes from the Proto-Slavic “xoxolъ” (lit. ”crest,” “tuft”).

“Victory Day” is a Soviet song written in 1975 to mark the 30th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II.

Volodymyr Saldo, head of the occupation administration of Kherson Region. Formerly a Ukrainian politician, People’s Deputy of Ukraine (2012–2014), three-time elected Mayor of Kherson (2002–2012), predecessor of Mykolaienko in this post.

Going to the bathhouse was hell. You run from one building to another, and they either keep beating you or set the dogs on you

When I first got to the cell, there were about 20 of us. A few days passed, and one of the guards said: “Our old guys are starting to look lighter” — meaning the bruises on our faces were fading, and that was “not right,” so they beat us again.

This is their routine: morning inspection, evening inspection, going out for a walk or to the bathhouse — and in one direction they beat you, and on the way back too.

Many people went mad. They couldn’t handle it; they wet themselves. Just from the pain, from fear. And how do you restore that psyche later, when a person comes home? When a person already reacts to every rustle, flinches, is tense, beaten down. And when they beat you on already beaten places, it is very painful. Because you know: now it is time for inspection, you already hear the shouting, and you start shaking. You know they will beat you. Not just beat you — beat you very badly.

On Oct. 1, 2022, I was transferred to a penal colony in Pakino, Penal Colony No. 7 in the village of Pakino in the Kovrov district of Russia’s Vladimir Region. At first, they treated us very aggressively there as well, but later it became somewhat calmer — perhaps because they believed we were already “processed,” that we had already been broken. There were rotations. They brought in new prisoners, and probably they no longer had enough strength for everyone. But at any moment they could take you out and beat you for no reason.

In February 2025 a new shift of guards arrived, and they were very harsh. You get used to being beaten. You understand that it will always be this way. But sometimes you realize that they are simply going to cripple you.

The word stems from the Russian name for the oseledets hairstyle, “khokhol” (Russian: хохол), and is commonly used as an ethnic slur for a Ukrainian. Oseledets is a Mohawk-type haircut that features a long lock of hair sprouting from the top or the front of an otherwise closely shaven head. The word comes from the Proto-Slavic “xoxolъ” (lit. ”crest,” “tuft”).

“Victory Day” is a Soviet song written in 1975 to mark the 30th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II.

Volodymyr Saldo, head of the occupation administration of Kherson Region. Formerly a Ukrainian politician, People’s Deputy of Ukraine (2012–2014), three-time elected Mayor of Kherson (2002–2012), predecessor of Mykolaienko in this post.

For example, they had their own rules of conduct: you had to walk with your head down, your hands up, in a certain posture. But I was physically and psychologically unable to do so. After one walk, one of the guards pulled me out of the cell, beat me up, and said, “I’ll break you, you’re going to do everything I say.”

The next day, for no reason, he punched me in the face. It hurt badly. And I had a purely human reaction, not rational, instinctive. I stood up. I did not realize that I was not supposed to straighten up, and he kicked me in the heart. The guys were probably reviving me for about an hour afterward.

That evening they took another guy from our cell. He was on duty and they didn’t like something he had done. He was a strong guy, a two-time master of sports. We heard them beating him in the corridor, and then they just threw him into the cell like a sack of meat. And then I understood: either they would cripple me or they would kill me.

I said, “I’m going on a hunger strike, because we have no other way to influence this at all.” The guards said, “Fine, if he also stops drinking, he’ll die faster.”

On the second or third day, the senior officer came. He said, “What happened?” I said, “They beat me up.” He said, “What are you imagining? We won’t let you die of hunger, we’ll force-feed you through a tube, through your nose. End the hunger strike.”

I said I wouldn’t stop, because I understood that this person had already targeted me. He would either kill me or cripple me. And it’s better…forgive me…it’s better this way [to die of hunger] than to walk around with wet pants later.

Apparently, he thought it would not look good for his career if a former mayor died in captivity after a hunger strike, and he said, “All right, stop it. They won’t beat you anymore.” I replied, “It’s not about me. It’s about all the guys. They beat that man so badly that a healthy adult was carried in like a piece of meat.”

He said, “Fine, I’ll give the order not to beat you.” That means it was a deliberate policy: first they beat us, then they stopped. And indeed, he kept his word. The beatings stopped. You can’t say they didn’t hit us at all. For them, slapping you on the ear during inspection or kicking you was normal. But the brutal beatings stopped.

This was already in 2025, when prisoners began to be released and people saw the condition they were in. Two guys were in my cell who before the war weighed about 120 kilograms, and in captivity they weighed about 62 to 64 kilograms. Imagine losing half your body weight. That’s horrific. There are just bones left, nothing else.

When you’re there, everyone looks the same to you. You don’t notice it or aren’t surprised. But when you come home and look at ordinary people, you realize how terrifying it all is.

This was in that hell, in the Vladimir Region. As for the reaction of doctors to all these beatings: a guy in our cell became very sick. His body temperature was around 40 degrees Celsius [104 degrees Fahrenheit] or higher. At the morning inspection, we said that someone in our cell was seriously ill. There was suspicion of appendicitis. He had pain in the lower right side of his abdomen. He was very unwell — vomiting, diarrhea, and a high fever.

They decided to send him to the hospital. Not because they felt sorry for him, but because they did not want the trouble of writing reports about a death and so on. And during intake at that hospital, imagine this, they smashed his kidneys. His legs were black. A doctor examined him and said, “You do not have appendicitis. When you return to Ukraine, see a doctor — something is rotting in your stomach.” And the man began to ask to be sent back to the prison. That was the medical care.

He was sent back. He lost four kilograms — and that was in the hospital, where they supposedly fed people a little better. I think they said they gave people eggs there. Half an egg once a week, I don’t remember exactly. Everyone talked about it. It was a dream to find something normal to eat, even a small piece of butter, because we had no normal food at all.

There was another doctor who liked to “treat” us for scabies by exposing us to the cold. Everyone had scabies. Those who completely lost control and scratched themselves raw were gathered in separate “wards.” He took away all their clothes, took away their thin blankets, and they were supposed to be “treated” for scabies like that. And the real solution was simple: a tube of benzyl benzoate — apply it and everything goes away.

Once I fell in the bathhouse and hit my head badly. By the time I reached the cell, I had filled the whole corridor with blood. The guards brought me snow from outside, made a lump, and pressed it to my forehead. Two days later, a doctor came. “Oh, what is this? Everything is covered in blood.” He gave me a piece of gauze, smeared something on it, and said, “put it on and hold it.” I held it. The next day the gauze dried. He came in and said, “Why are you not holding it?” I said, “It is dry.” He said, “No, I told you to hold it.” I said, “Are you making a fool out of me?”

I felt like I had a concussion. I could not tell left from right. And he said, “you are fine.” And if you did not hold the dry gauze, they made you put a food bowl on your head and stand in the corner. One man refused, and the doctor told the guards to beat him harder. They came to do it specifically in the evening.

Until June 2024, they fed us extremely poorly, then it became a little better. In the morning and evening there was porridge, but so little that it could not be called food. Usually it had no salt or sugar. For lunch they gave us potato peelings — what we throw away when we peel potatoes. That was what they gave us to eat. We survived mainly on the piece of bread we were given for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

The word stems from the Russian name for the oseledets hairstyle, “khokhol” (Russian: хохол), and is commonly used as an ethnic slur for a Ukrainian. Oseledets is a Mohawk-type haircut that features a long lock of hair sprouting from the top or the front of an otherwise closely shaven head. The word comes from the Proto-Slavic “xoxolъ” (lit. ”crest,” “tuft”).

“Victory Day” is a Soviet song written in 1975 to mark the 30th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II.

Volodymyr Saldo, head of the occupation administration of Kherson Region. Formerly a Ukrainian politician, People’s Deputy of Ukraine (2012–2014), three-time elected Mayor of Kherson (2002–2012), predecessor of Mykolaienko in this post.

For lunch they gave us potato peelings — what we throw away when we peel potatoes

Sometimes we had walks in a concrete yard, and behind the fence grass was growing. We saw that it was nettle, picked it, shared it among the whole cell — three or four leaves each — and were happy that we had at least some vitamins.

It burns your hands — it’s nettle, after all — but you eat it anyway because you understand that there are no other vitamins. That’s how we survived.

The word stems from the Russian name for the oseledets hairstyle, “khokhol” (Russian: хохол), and is commonly used as an ethnic slur for a Ukrainian. Oseledets is a Mohawk-type haircut that features a long lock of hair sprouting from the top or the front of an otherwise closely shaven head. The word comes from the Proto-Slavic “xoxolъ” (lit. ”crest,” “tuft”).

“Victory Day” is a Soviet song written in 1975 to mark the 30th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II.

Volodymyr Saldo, head of the occupation administration of Kherson Region. Formerly a Ukrainian politician, People’s Deputy of Ukraine (2012–2014), three-time elected Mayor of Kherson (2002–2012), predecessor of Mykolaienko in this post.

They also really liked to make us sing for them. That was their preference, just like in Soviet times, during World War II. Their favorite songs were “Katyusha” and “Victory Day.” They would stand at the entrance to the cell, and from morning until evening you had to sing “Katyusha” or “Victory Day” for them. Without stopping. The only break was to eat quickly. From wake-up to lights out, everyone had to sing.

If someone was sick, if he could no longer sing, they would come in and beat everyone. They treated it as a kind of collective responsibility, collective punishment. When I couldn’t do something, I’d say, “Guys, just beat me right away, because I’m not going to do this,” and they would reply, “No, we’ll beat everyone because you are refusing.”

In the last cell I was in there were 10 to 12 people. The cell was about 10 to 12 meters in size — a small open toilet, a sink, and bunks around the perimeter — with maybe one and a half by one and a half meters, or a little more, of free space where you could walk in a circle, brushing against each others’ shoulders.

Winter was even harder. In 2024, Ukraine sent thermal underwear. We were so happy that at least we could keep warm somehow, because they often forced us to open the windows, and outside it was minus 10 to minus 20 degrees Celsius. That was normal. Sometimes it was even colder, but you had to open the window so that it would “smell like spring” for them. Cold air came in and immediately froze on the windows, and you were shaking from the cold. Sometimes they took our clothes “to be washed.” And for two or three days we walked around wearing only underwear and a T-shirt.

Our entertainment was rats and mice, but that was in Voronezh. We even fed them, tried to tame them.

I tried to hold on. Faith helped a lot, the belief that Ukraine was fighting — fighting for itself and fighting for us, for those in captivity. Time passed and the exchanges began. We believed these were real exchanges. Sometimes people were just transferred to other colonies, but we believed that if they were taking us, then their soldiers were being captured. That meant things were not as good for them as they told us. They told us that all of Ukraine had already been captured, that it was already Russia, that everything was over.

Most of all, supporting each other helped a lot. It worked miracles. You understand that you feel very bad, but you see that someone else feels even worse, and you try to help. And it worked. Of course, the desire to see my family helped too — the belief that they were waiting for me, that I had to return.

“There they kill you for being a ‘khokhol,’ and here they rejoice because you are Ukrainian”

Until I saw Ukrainian territory and our buses with flags, I could not believe that I was being taken for an exchange — not even when they transferred me to a cell that we called the “portal.” People were taken there, changed into different clothes supposedly for an exchange, and then two or three weeks later they were returned. There were cases when people were already taken to the border and not handed over. Why, I do not know.

On Aug. 19, 2025, they brought me there, to that cell. There were already three people: Dima Khilyuk, a correspondent for UNIAN; Yevhenii Vovk; and another man, Dmytro. He had mental problems. He had been badly beaten in Bryansk, then spent five months in solitary confinement and lost his mind.

They dressed us in military uniforms. I even fell asleep. I thought maybe they would take us at night. But in the morning they scattered us back to our cells and said, “Ukraine does not want you, you are not needed by anyone.”

The next day they took me and Dmytro out, put us into a prison van, and drove us to Moscow, to an airfield. There were about 50 people there. We sat for a full day, without toilets, without anything. Then a plane and Belarus. There they told us to take off our blindfolds and untied our hands. There were buses, food, and half an hour later, the border. We were still afraid it was a trick.

And you know what was interesting? We were walking toward our buses, smiling, shouting, and opposite us was a group of Russians who were being exchanged. There was not a single happy face among them. They looked frightened, depressed. I never understood why.

For us, it was a miracle. You get used to being starved, beaten, humiliated, tortured with propaganda there in Russia. And here you return, and from the border all the way to Chernihiv people are standing in lines — with flags, with signs, with smiles. They are happy for you. They congratulate you. You feel such love for yourself. It is impossible to forget. There they kill you for being a “khokhol.” And here they rejoice because you are Ukrainian. It really is a miracle. You never forget things like that.

And the air, it heals you. You understand that you are home. This love from people, this familiar air, these smiles make you forget the pain, your ailments. And immediately you get the feeling that you are the happiest person in the world.

The word stems from the Russian name for the oseledets hairstyle, “khokhol” (Russian: хохол), and is commonly used as an ethnic slur for a Ukrainian. Oseledets is a Mohawk-type haircut that features a long lock of hair sprouting from the top or the front of an otherwise closely shaven head. The word comes from the Proto-Slavic “xoxolъ” (lit. ”crest,” “tuft”).

“Victory Day” is a Soviet song written in 1975 to mark the 30th anniversary of the defeat of Nazi Germany in World War II.

Volodymyr Saldo, head of the occupation administration of Kherson Region. Formerly a Ukrainian politician, People’s Deputy of Ukraine (2012–2014), three-time elected Mayor of Kherson (2002–2012), predecessor of Mykolaienko in this post.