Belgian authorities are expected to make a decision soon regarding the extradition of Sitoramo Ibrohimova, a refugee from Tajikistan. There is growing concern that she may face the same fate as her sister, 27-year-old Nigora Saidova, who was deported to Tajikistan along with her seven-month-old daughter after being accused of aiding and abetting terrorism — charges that have been fabricated, according to data available to The Insider. Upon her return to Tajikistan, Saidova was sentenced to eight years in one of the country’s most notorious women’s prisons, known for its rampant abuse and torture. Year after year, Poland consistently denies refugee status to Tajiks, often over purported ties to terrorism, placing them among the top three most denied groups, alongside Russians and Iraqis. Critics have presented credible evidence that Tajik President Emomali Rahmon exploits fears of ISIS to target the families of people who have fled the country, using the terrorist group’s fearsome image in the West as a tool for achieving the extradition of political activists and their families back to Dushanbe. An investigation by The Insider and the Polish weekly Polityka reveal that European authorities frequently make little effort to go into the details of each case, leading to the frequent extradition of individuals against whom accusations have been knowingly falsified. According to human rights activists, some of these deported individuals are handed over to the Russian authorities, who interrogate them at the Russian 201st Military Base near Dushanbe, where they are tortured and forced to confess their non-existent ties with Ukraine.

This is a joint investigation with Polityka (Poland).

In April 2024, the Polish Internal Security Agency issued a press release announcing the successful execution of a special operation that led to the capture and deportation of an unnamed Tajik national, who was described as a dangerous ISIS militant hiding out in Poland with the help of false documents. No other details were given. The announcement followed shortly after the March 22 terrorist attack at Crocus City Hall outside of Moscow. ISIS-K (Islamic State Khorasan), the Islamic State’s Afghan branch, claimed responsibility, and several Tajik citizens were arrested in Russia the following day. According to Polish authorities, the individual they detained in April was also linked to this terrorist group.

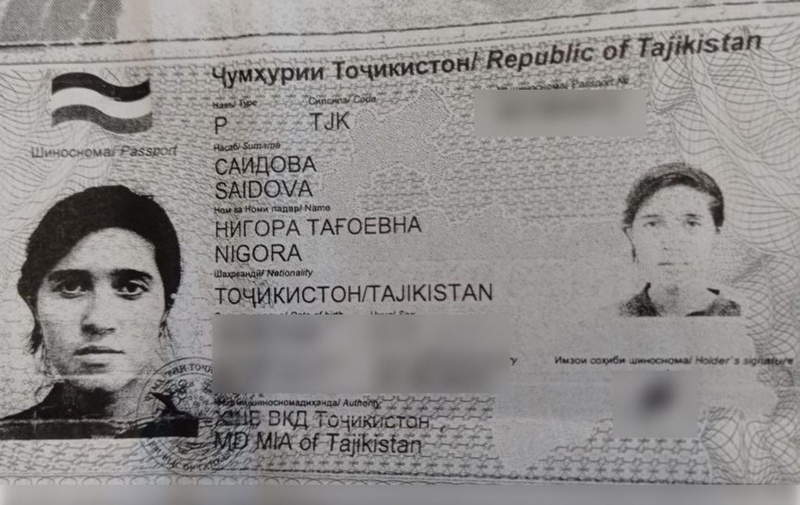

What the Polish press release failed to disclose was that the “target” of the operation had already been in a Polish prison for two years. 31-year-old Usmon Shamsov had fled the war in Ukraine and persecution by the Tajik regime, seeking refuge in Poland, The Insider and the Polish weekly Polityka have learned. He indeed entered the country using a fake driver's license under the name Usmon Aliyev — not in order to engage in terrorism, but to avoid extradition to Tajikistan. After two years of legal battles, Polish authorities eventually deported him back to his country of citizenship, where he faced imprisonment. A year prior, Shamsov's wife, 27-year-old Nigora Saidova, along with their seven-month-old child, was quietly deported to Dushanbe from Poland — this despite a court order against her extradition.

Nigora Saidova went through a detention center, a prison, a prison hospital, and a closed refugee center in Poland. She was detained on February 28, 2022 at the Medyka border crossing, where she, her husband, their children, and her sister, Sitoramo Ibrohimova, had come from Ukraine, fleeing the Russian invasion. It turned out that Tajikistan had declared Saidova wanted through Interpol on charges of mercenarism. Seven months pregnant, she was separated from her husband and two children (ages two and three).

Documents reviewed by The Insider and Polityka show that Tajikistan's charges against Nigora Saidova were fabricated. According to Tajik investigators, on March 23, 2018, Saidova allegedly flew from Dushanbe to Istanbul, and then, on her sister’s advice, traveled to Syria, where she married a member of the Islamic State and became its active participant.

But the Tajik authorities’ version of events does not correspond with established facts. Saidova and her sister had been living in Ukraine since January 12, 2018. The date of Saidova’s border crossing was confirmed by two sources in the Ukrainian security services. The Ukrainian officers also said that Saidova did not leave the country again until the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. The date of Saidova’s entry into Ukraine is further corroborated by a border stamp in Ibrohimova’s passport, showing that she, too, entered the country on January 12, 2018, confirming the sisters traveled to Ukraine together.

The claim that Saidova married an Islamic State fighter in Syria is also false. She married cab driver Usmon Shamsov (they entered into a religious marriage, a nikah) on April 6, 2018 in Kyiv. A copy of the document confirming the marriage was made available to The Insider. Shamsov had been living in Ukraine since 2016, and the couple remained there with their children until they left the country in February 2022.

It is also highly improbable that Saidova could have entered ISIS-controlled areas in Syria via the Turkish border in March 2018. By that time, ISIS had been nearly defeated and controlled only two small enclaves in the south of Syria, far from the Turkish border. To reach these areas, Saidova would have had to cross territories held by groups hostile to ISIS.

The indictment against Saidova, prepared by Tajikistan’s security forces, was poorly constructed; it suggested that all of her alleged “crimes” occurred on a single day — March 23, 2018. Furthermore, numerous errors were made during her case, starting with the Polish border guards' interrogation and continuing through the actions of the Polish prosecutor and the court.

Tajikistan’s indictment against Nigora Saidova was poorly constructed; it suggested that all of her alleged “crimes” occurred on a single day — March 23, 2018

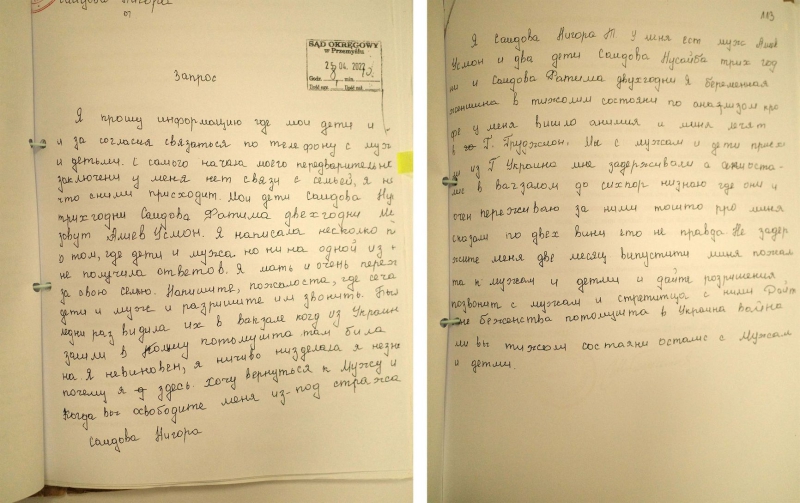

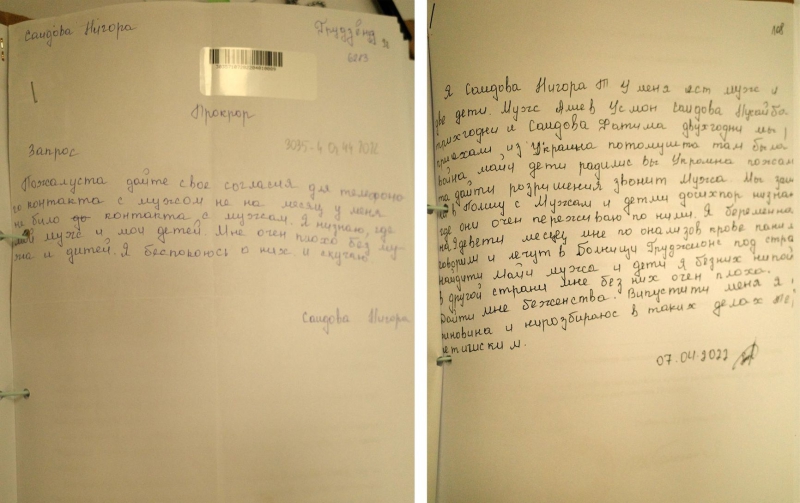

Despite these circumstances, Saidova was arrested and held in detention for several months. She was unable to communicate or defend herself effectively, as she was not provided with a Tajik interpreter. Instead, prison staff attempted to communicate with her using an electronic translator. Saidova, struggling to express herself, resorted to writing in broken Russian, and was barely able to convey even the simplest requests to the prison guards:

“I ask for a diet without meat because I don't like it. I can't eat meat food, thank you, Saidova Nigora.”

The documents show that the pregnant Saidova suffered from anemia. As a Muslim, she likely avoided eating meat out of concern it could be pork.

According to Saidova's case file, reviewed by The Insider and Polityka, court sessions were often brief — some lasting only five minutes — and were frequently conducted without her presence. Her asylum requests were consistently ignored.

Peter Sura, the appointed lawyer representing Saidova, noted that the number of extradition hearings in Poland surged in early 2022 due to the massive influx of people at the border following the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Saidova, he remarked, was “caught in the gears of the machine.” The accusations of terrorist involvement further complicated her situation. One might expect that an extradition request from a country known for human rights violations would trigger caution and warrant a thorough examination. However, in Saidova's case the opposite occurred: Polish officials appeared genuinely motivated to collaborate with Tajik investigators.

The case materials include correspondence between Polish prosecutor Barbara Rzuchowska of the National Prosecutor's Office's Bureau of International Cooperation and Manuchehr Makhmudzoda, head of the Foreign Economic Cooperation Department at Tajikistan's General Prosecutor's Office. Rzuchowska, concerned that the period of Saidova's detention was coming to an end — and that the pregnant woman would soon need to be released — urgently requested the court to provide the necessary documents for her extradition. She went as far as providing her Tajik counterpart with specific wording for the letter to ensure it would be accepted in court.

While in prison, Nigora Saidova penned desperate letters — to the prosecutor, the court, and, sometimes to no specific addressee. Nearly all of these letters went unanswered.

On April 26, 2022, while in prison, Nigora Saidova gave birth to a daughter and named her Rabiya, derived from the Arabic word “spring.” Ten days after Rabiya’s birth, Saidova wrote another letter, pleading: “Please release me so that I can find my husband and children.” The court responded that, “We have no information about your husband's whereabouts with the children” — this despite the fact that Saidova’s sister, Ibrohimova, who was caring for Saidova’s children at the time, had been searching for Saidova through the Red Cross. And Saidova’s husband was imprisoned in Poland.

In June 2022, a court in Przemyśl highlighted numerous errors in Tajikistan’s indictment documents and concluded that it was impossible to make an extradition decision based on them. The court requested additional information from the Tajik prosecutor's office, but the documents were slow to arrive. The detention period expired, and Saidova was temporarily set free. However, immediately after her official release, border guards detained her and her infant daughter, placing them in a secure refugee center in Kętrzyn, a town in northeastern Poland.

“In my experience, courts often mechanically approve applications from the Border Guard,” said Zuzanna Kaciupska, an advisor with the Association for Legal Intervention, a group that provides free legal assistance to migrants and refugees in Poland. She noted that individuals could not be placed in such centers if it might endanger their life or health — a situation that clearly applied to the mentally exhausted Saidova and her two-month-old daughter.

When Saidova and her infant daughter found themselves in the refugee center, the border guard decided to deport them. Unlike extradition, deportation in Poland, as in other EU countries, does not require a court decision and is treated as an administrative matter. Several reasons were cited: Saidova had no visa, no means of subsistence, and her presence in the country was deemed a potential security threat. On October 19, 2022, Saidova and the seven-month-old Rabiya were deported on a regular flight and handed over to Tajikistan’s security forces upon arrival in the country’s capital, Dushanbe. Poland's border guard did not respond to any inquiries from The Insider and Polityka regarding Saidova's case.

Saidova was sentenced to eight years in prison and sent to the only women's correctional colony in the city of Nurek. She has been completely cut off from the outside world, with no access to letters, phone calls, or visits — leaving her family uncertain if she is even alive. In Tajikistan, it is nearly impossible to find a lawyer willing to represent someone facing such charges. Former prisoners describe the colony to which Nigora was sent as “hell on earth.”

Rabiya's fate remains unknown.

Saidova was sentenced to eight years in prison and completely cut off from the outside world, with no access to letters, phone calls, or visits

Saidova’s sister, Sitoramo Ibrohimova, is currently in a deportation prison in Belgium, where she is fighting to prove her innocence in a similar case. If she is unsuccessful, she may face the same fate as Saidova. Sitoramo has four children of her own, along with Saidova’s two eldest daughters, who remain in her care.

Human rights activists, along with Ibrohimova’s lawyers, highlight the risk that she will be tortured if sent back to her home country. The case of Saidova, who was extradited by Polish authorities, may serve as a crucial precedent in their efforts to prevent a similar tragedy from befalling Ibrohimova.

Both sisters were placed on Interpol's red list at the request of Tajik authorities. On the day Saidova was arrested in Poland, Ibrohimova narrowly avoided a similar fate thanks only to errors made by border guards when inputting her surname into the Interpol system — they made two mistakes when entering “Ibrohimova” in the Latin alphabet — which prevented the warning system from activating.

Ibrohimova’s case is fraught with inconsistencies that could potentially influence the Belgian authorities' decision and prevent her extradition to Tajikistan. Her case file was made available to The Insider and Polityka.

According to the documents, Ibrohimova — a mother of three at the time, whose children were born in 2011, 2012, and 2015 — took her kids to Turkey in 2016 to join ISIS militants, underwent combat training in an ISIS camp, and participated in combat operations in Syria.

However, other records, including passport stamps, Ukrainian border database entries, and the case file of her husband, Murodali Halimov, suggest an entirely different narrative. In the version of events that corresponds with these documented facts, Ibrohimova arrived in Turkey on February 1, 2016, to join her husband. Four months later, she was left alone with her children when Halimov set off for Ukraine, intending to return for her at a later date. Halimov, however, was detained at Kharkiv airport on June 26, 2016, and he immediately sought political asylum.

Halimov remained in custody for a year following an extradition request from Tajikistan but was released afterward and continued to reside in Ukraine. Eighteen months later, on January 12, 2018, Ibrohimova, along with her children and sister, Saidova, traveled to Ukraine to visit him. But Halimov soon ended up in Tajikistan nevertheless.

“My husband was kidnapped in 2018 in Ukraine, near our house, in front of my eldest son Mohammed. He was sent to Tajikistan and convicted without a fair trial, without testimony, without evidence. He was sentenced to 23 years in prison. I don't know what is happening to him now,” Ibrohimova said during her asylum interview in Belgium.

“I'm on the blacklist too, if I get there [to Tajikistan], I'm very afraid of torture. Women are mistreated in detention. I'm very afraid of being sexually assaulted. […]

In 2019 or 2020 my parents were threatened. [The authorities] demanded them to force me to come back. I’m very afraid to go back there. I would like to be able to study and earn a living. Now I am responsible for six children.”

The charges against Nigora Saidova and Sitoramo Ibrohimova appear to have been fabricated by the authorities in Tajikistan due to their family ties. Tajikistan’s security forces have been persecuting the family of Ibrohimova’s husband, Murodali Halimov, for years, resulting in the imprisonment or death of more than 15 family members. When questioned about her asylum application, Ibrohimova told Belgian authorities that their troubles began in 2015, and that they were linked to her husband's brother, Khuchbart Halimov.

“His brother denounced the regime. He was dissatisfied that we had rights or laws. […] My husband's brother never preached Islam. He was accused of preaching Islam and of being an extremist and terrorist. All of these accusations are false. As a result, his other brothers and two nephews, one of whom had just turned 18, were arrested one after the other.”

In 2018, Tajikistan successfully secured the extradition of Ibrohimova’s husband, Murodali Halimov, from Ukraine under circumstances that resembled a kidnapping: four unidentified men forcibly dragged Halimov into a car in front of his young son and took him away. This was preceded by an information campaign to discredit him, which began with a report from Radio Liberty's Radio Ozodi project. The journalists echoed the claims made by Tajikistan’s security forces, who accused Halimov of links with ISIS and claimed that he fought on behalf of Ukraine in the so-called “Donetsk People’s Republic” (or “DPR”). The news story relied on the testimony of an individual detained by the security forces.

Interestingly, the accusation of ISIS involvement did not emerge immediately. In the early stages of the criminal case, Tajik authorities accused Halimov of being part of Jamaat Ansarullah. This organization, which mainly consists of Tajiks and aligns itself with the Taliban, represents the Tajik political opposition to the Rahmon regime. Case documents obtained by The Insider and Polityka highlight these early accusations. In later allegations, Tajikistan's claims of ISIS ties among Halimov's relatives appear all the more unconvincing given that Jamaat Ansarullah is ideologically opposed to ISIS. As Muhiddin Kabiri, leader of the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan, explained in a conversation with The Insider and Polityka, it is often more convenient for Tajik authorities to present members of Jamaat Ansarullah and other associations as supporters of ISIS because it “gives a more negative impression to Europeans.”

According to Anwar Derkach, a Ukrainian human rights activist who heads the “Helping Hand” («Рука допомоги») foundation, Halimov was tortured after his extradition to Tajikistan at Russia's 201st Military Base near Dushanbe. Under duress, he was forced to testify about alleged ISIS training camps in Ukraine — a narrative that Russian propaganda has been actively promoting since 2016. Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan leader Kabiri also confirmed that he knew about the torture of Tajiks who had been to Ukraine — torture carried out at Russia’s 201st Base:

“Russian law enforcement officers have created a joint headquarters with the Tajiks, and Russian investigators are working in Tajikistan. If someone is sent to a Tajik prison, the Russian officers will have access to him if the person has something to do with Ukraine. They interrogate people from Poland, Ukraine, and the Baltic states. If, under torture, a Tajik prisoner claims that ISIS members were trained in Ukraine, this is then circulated through Tajik domestic media in both Russian and Tajik languages — and part of the population believes it.”

The practice of persecuting people not for specific crimes, but because they belong to the families of the opposition, is widespread among Tajik security forces, says Helping Hand’s Derkach.

Kabiri confirms this point as well:

“The families of the opposition are hostages of the regime in Tajikistan. Collective responsibility fits into the logic of the authorities. Imagine the agony an opposition activist goes through in Tajikistan. It's very difficult to explain to European officials. My ninety-year-old father flew to see his grandchildren, but they took him off the plane and interrogated him, mocked him, called him a traitor's father. He was already sick, and they hastened his death. My older brother has not been allowed to use the internet or telephone for seven years, every week he has to register at the police station. My four-year-old grandson with cancer was not allowed to go to Turkey for treatment. Our relatives are hostages.”

Kabiri himself was also wanted by Interpol under a “red notice” for alleged Islamic terrorism. “Many of my fellow opposition activists are still on Interpol lists,” he says.

“Europe is very sensitive about Islamic terrorism and radicalism, so they [Tajik authorities] accuse all their opponents of Islamic extremism and terrorism. Ordinary police officers or those who deal with migrant issues, they are not all experts and don't know what our party is. They just say, ‘It's better to be extra safe. Why do I need to figure out who's who? Here is the list. The Tajik authorities say they are accused. Better get rid of them all.’”

The Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan was banned only in 2015. Before that, it participated in elections on an equal footing with Rakhmon's People's Democratic Party — as the only legal Islamist party in Central Asia. Now, Tajik citizens unwanted by the regime cannot expect “the same treatment as opposition activists from Russia or Turkey, even Iran and Afghanistan,” says Kabiri.

“I meet with European politicians and officials and try to explain the situation, and I wonder why they have a certain attitude, for example, to the Belarusian opposition, while they are very soft on Rakhmon's actions. And they say: ‘Because Rakhmon is not a problem or an opponent for us. He is fighting against the Taliban. He is a dictator, but he defends secular values, he is against religious radicalism.’ And all our attempts to explain to European politicians that they should avoid double standards and should use a single criterion towards all migrants are useless.”

Aside from Interpol prosecutions, the Rakhmon regime employs other tactics, such as placing undesirable individuals on financial monitoring lists that are recognized by banks across Europe. According to Kabiri, this makes it all but impossible for these individuals — including those who have been granted refugee status in Europe — to open bank accounts and legally integrate into society.

Human rights activists report that the situation regarding the deportation of Tajik citizens is similar across European countries. Year after year, Poland consistently denies refugee status to Tajiks, placing them (1, 2) among the top three most denied groups, alongside Russians and Iraqis. Despite the relatively small number of Tajik asylum seekers — just over 100 annually — Poland's rejection rate is notably high.

The Insider and Polityka extend their gratitude to the human rights organization Freedom for Eurasia for its assistance in preparing this investigation and for providing some of the key documents.