Neither Donald Trump nor Elon Musk — who briefly took on the role of the president’s fiscal enforcer — managed to solve the problem of the U.S. budget deficit. Import tariffs may have helped Trump reduce the May deficit by 9%, but in the long run, the duties are likely to hurt domestic manufacturers and lead to an overall drop in revenue. Musk’s efforts also failed to produce any meaningful improvement. The core issue facing the U.S. isn’t the size of the existing debt, but the fact that it keeps growing. Economists have a clear solution for halting that growth and reducing the deficit — but it’s one Americans won’t want to implement.

During both his campaign and his early days in office, Trump made a series of bold economic promises, including commitments to cut the budget deficit and rein in the national debt. He launched a trade war under the same banner. Musk’s team took budget cuts so seriously that it sparked internal conflict and public debate — but ultimately yielded no visible results.

How the U.S. got into debt

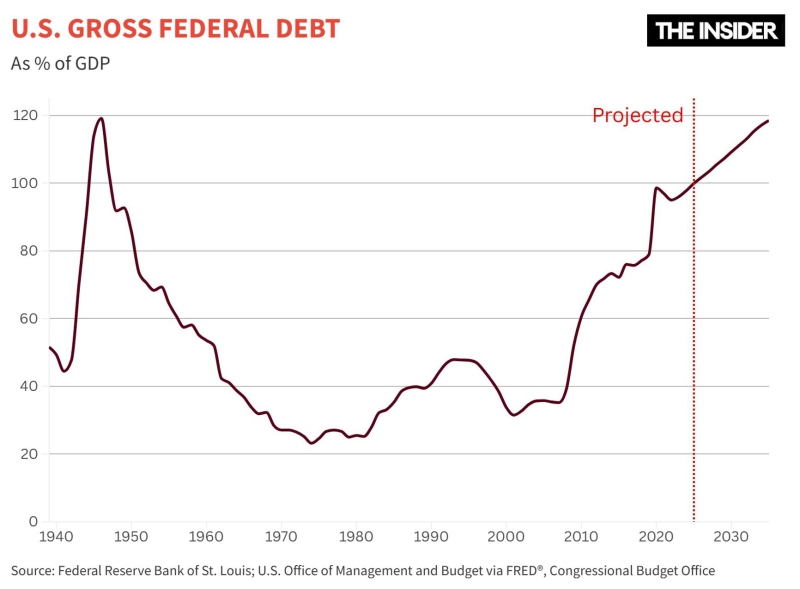

Since the early 2000s, the U.S. national debt has been growing at a historically rapid pace. It now stands at 124% of GDP.

Why is this a problem? Although the analogy is imperfect, in many ways a government’s finances really do work much like a household’s. A family can borrow money to pay for major purchases — a mortgage for a home, a loan for a car. Debt might also be necessary in emergencies: medical expenses, urgent repairs, natural disasters, or accidents. In good years, the family repays these loans out of current income. We borrow when the need is urgent (a crisis) or when there is a clear economic benefit (a low-interest mortgage or car loan).

In the mid-20th century, the U.S. behaved like a responsible household: the national debt soared during World War II in order to cover essential expenses, and then it declined during peacetime. However, starting in the 1970s, a pattern of continuous debt growth emerged. Military spending and macroeconomic crises triggered more borrowing, and the government gradually got out of the habit of paying it down during stable periods — with the exception of the period of 1998–2001, when the Clinton administration briefly managed to eliminate the budget deficit, thereby reducing the debt. Since then though, borrowing as a share of GDP has steadily increased.

We know from household experience that uncontrolled debt growth is unsustainable. Sooner or later, a family whose means and ends get too far out of balance goes bankrupt — it defaults and loses its assets. Even without bankruptcy, a high debt burden puts pressure on household finances, with loan payments eating up a significant portion of the budget.

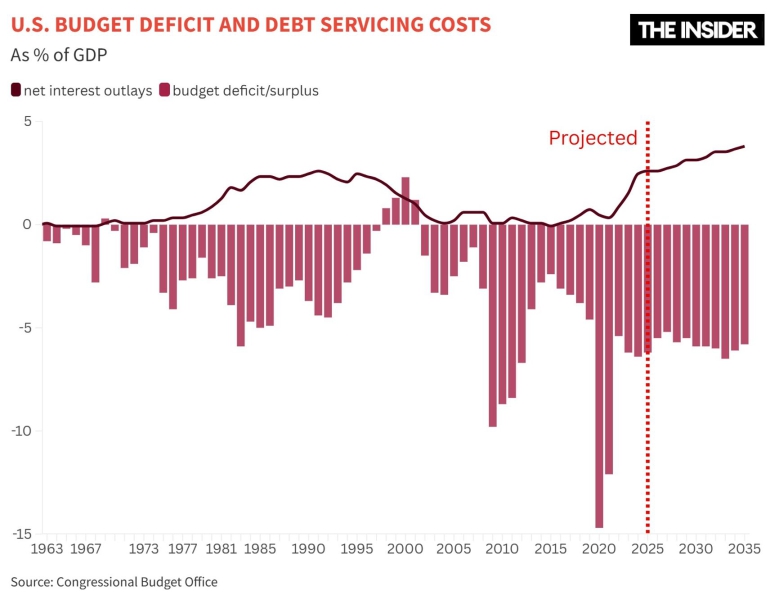

The same goes for the government, and debt servicing is an increasingly large line item in the U.S. federal budget. A sovereign default won’t lead to literal confiscation of property, but it can trigger other serious consequences.

In the early 2000s, developed countries fell into a tempting type of “debt trap.” Beginning in the 1990s, real interest rates (adjusted for inflation) on government debt in advanced economies began a long downward trend. There were several reasons for this. Emerging markets were getting richer, and their governments and citizens wanted to store value in safe instruments. Meanwhile, private investors in developed countries also ramped up demand for government bonds.

Rising demand allowed governments in developed countries to borrow at ever-lower interest rates. Among them, the U.S. stood out as the prime example of “reliable credit”: thanks to its reputation as a trustworthy borrower, Washington enjoyed unmatched access to cheap money. Older debt didn’t need to be repaid — it could simply be rolled over into new loans at lower rates.

Thanks to its reputation as a reliable borrower, the U.S. had easier access to cheap credit

If a household were to be offered loans at ever-lower interest rates, why wouldn’t it take them? It’s entirely rational to seize such an opportunity. Between 1990 and 2024, the average government debt-to-GDP ratio among OECD countries rose from 37% to 111%. In the 2010s, real interest rates on government debt even fell below zero — meaning governments could borrow at rates lower than inflation! Now, however, the reckoning has begun.

After spiking during the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation has started to ease, while real interest rates on government debt have begun to climb. The bill is coming due, and the cost of servicing accumulated debt is becoming a painful burden for national budgets. This is likely one reason behind the ongoing public feud between President Trump and Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell. The administration would benefit from lower interest rates, but Powell and his committee have so far refused to oblige.

As of the 2025 fiscal year, U.S. federal spending on debt servicing — that is, interest payments on government bonds — is projected to account for 16.6% of total budget expenditures, or 3.2% of GDP. As a percentage of federal spending, that’s the highest level seen in America since the 1990s — and as a share of GDP, it’s already at an all-time high, and it is forecasted to grow. Perhaps the only item on the political agenda where Democrats and Republicans agree is this: the status quo is unsustainable. The trajectory of ever-growing debt must be reversed.

How dire is the situation?

Russian media audiences have long been exposed to predictions of an imminent U.S. budget meltdown and attendant collapse of the dollar — and they have grown skeptical as a result. But how dire is the situation really? And how urgently does it need to be addressed?

Interest payments amounting to 3% of GDP aren’t a huge sum. Imagine a household budget: spending 3% of your income on loan payments is quite reasonable. You could compare it to mortgage debt — holding a balance equal to 124% of annual income would actually be considered modest, maybe even conservative. But these household analogies can be misleading.

The key difference is that governments don’t borrow once — like a family taking out a mortgage — but finance their operations year after year. They also have to continually roll over portions of the debt, paying off old bondholders and issuing new debt. If the budget runs a deficit every year, creditors (meaning the global financial market) may start to believe the borrower (the U.S.) will eventually become insolvent. This drives up the interest rate on a country’s debt and increases the cost of servicing it. In other words, a government can overplay its hand in “selling reliability” — and end up selling it off entirely.

How close are we to a crisis?

Russian readers have their own historical frame of reference. In 1998, annual interest payments on Russian treasury bills (GKOs) exceeded the country’s total annual tax revenues by 40%. The U.S. — and other OECD countries — are nowhere near that kind of insolvency.

Still, if you had asked an expert in the early 2000s what they thought about a hypothetical debt level at 124% of GDP, they’d likely have sounded the alarm and issued dire forecasts. Yet today, that figure is only slightly above the OECD average. The prolonged era of low interest rates seen in the 2000s and 2010s reshaped our understanding of what constitutes a sustainable debt level. But now that rates are rising again, there’s real cause for concern.

A political problem

The central issue isn’t the size of the debt that has already been accumulated, but the fact that it continues to grow. Debt increases for as long as the government can’t balance its budget, and the budget, in turn, is the result of a political process — which makes the problem a political one.

There are only two ways to balance a budget: cut spending or increase revenue — and sound policy typically relies on a combination of both.

In a modern state, government revenue comes primarily from taxes. But raising tax rates is deeply unpopular with the public — regardless of their political leanings. Traditionally, the Republican Party in the U.S. has advocated for tax cuts, and many wealthy individuals vote Republican precisely out of self-interest.

The Democratic Party, which has historically supported higher taxes on the rich, has in recent years come to rely more heavily on the support of the urban, educated, and affluent middle class. That makes it increasingly difficult for Democrats to push for tax hikes, as even educated and civic-minded people are reluctant to vote against their financial interests. Advocating for higher taxes risks eroding electoral support.

Even educated and civic-minded people struggle to vote against their financial interests

Among Republicans, the idea that tax cuts “pay for themselves” remained popular for a long time — the belief being that lower taxes would spur economic activity, and that the resulting growth would generate enough additional revenue to offset the losses from the tax cuts. But studies have shown that the miracle doesn’t happen — economic growth does not make up for the shortfall. Quite simply, lowering tax rates leads to lower tax revenues.

One of the key points in Donald Trump’s campaign platform was raising import tariffs in order to compensate for the lost tax revenue. It’s an idea that made sense in the early 20th century, when international trade mostly involved finished consumer goods or raw materials, and government budgets represented a much smaller share of GDP. But today, 52% of global trade consists of intermediate goods — components and materials used by domestic companies in their own production processes. Tariffs hurt not only consumers, but also domestic producers.

On top of that, declining trade volumes also hurt domestic exporters, and all of this suppresses overall economic activity. The experience with steel tariffs during Trump’s first term showed that while some steelmakers benefited, the tariffs inflicted net losses on the U.S. economy as a whole.

Other ways to boost tax revenue

One option is to increase overall economic growth. Intensive growth — driven by technological innovation — is constantly happening, but major breakthroughs can’t be planned. Sustainable growth comes from increasing the supply of productive factors: capital and labor. Capital inflows into the U.S. are already being encouraged, including through tax incentives. As for labor, growth can come from expanding the workforce; however, with unemployment already low, that means convincing people who previously had no intention of entering the labor market to start working.

A second option is to admit more immigrants. That’s precisely why both Republican and Democratic administrations have typically done little to stop illegal immigration despite publicly speaking out against it. Now though, the Trump administration is pursuing a visibly anti-immigration policy — one that will do nothing to support future tax revenue growth.

Can spending be cut?

Given that raising revenue would trigger a political and economic backlash, perhaps the solution to America’s debt problem lies on the spending side?

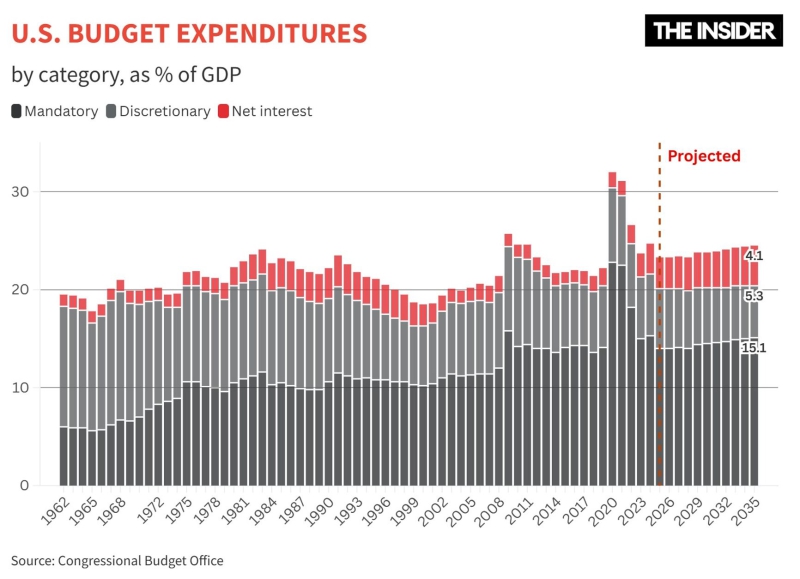

The bulk of the U.S. federal budget goes to mandatory spending — expenditures already promised by the government. These include Social Security payments, welfare benefits, and healthcare spending for seniors and low-income citizens. A smaller portion consists of discretionary spending — items that, by law, can be reduced. Part of this segment is earmarked for defense and veterans' benefits, which are also essentially promised. That leaves a relatively small slice of the budget that can be cut without inviting significant political or legal challenges.

In the early months of Trump’s new term, several high-profile cases involved cuts to this category. USAID programs were shuttered, along with funding for the federal Department of Education, scientific research through the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Science Foundation (NSF), NASA, and NOAA weather-related programs. These are easy political targets — after all, scientists don’t have a lobbying base to defend them.

But cutting programs that directly affect residents’ well-being and the popularity of lawmakers — such as various transportation, manufacturing, and agriculture projects — would be far more challenging. In political terms, these are known as “pork,” and the support that senators and congressmen enjoy in their home states often depends on their ability to serve it to their constituents — in the form of federal spending, programs, and subsidies.

That creates a problem. Experience shows that targeting “easy cuts” alone is insufficient to trim a meaningful portion of the budget. For example, the entire outlay for USAID represents just 0.3% of federal spending, while NSF receives only 0.1%. Even more importantly, Trump critics are fond of pointing out that these programs offer high returns on investment. NSF grants, for instance, can generate up to $3 in additional GDP for every $1 invested thanks to the technological advancements they help bring about. In other words, due to the work of Trump and Musk, the U.S. risks sacrificing its global scientific and technological leadership in exchange for negligible savings.

Efficiency of government spending and Elon Musk’s DOGE

If cutting or eliminating programs isn’t an option, perhaps savings can come from improving the way money is spent? That was the stated goal of Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE).

The premise was that government operations are inefficient — plagued by waste, redundant staff, and fraud — meaning that by identifying unnecessary expenses and optimizing processes, substantial savings could be achieved. Bureaucracies tend to be bloated, slow to change, and resistant to reform. Overcoming this inertia requires swift, decisive action and a willingness to disrupt established routines.

Interestingly, the idea of radically overhauling the U.S. government did not originate with President Trump or Elon Musk. The intellectual driving force behind it was programmer, entrepreneur, and philosopher-blogger Curtis Yarvin. Yarvin captivated his audience with a series of provocative, radical ideas — including dismantling the current government system and even establishing a technocratic dictatorship. He also coined the memorable slogan RAGE: “retire all government employees.”

Musk and his DOGE took on the task. Early reports purportedly uncovered numerous glaring anomalies: Social Security databases listing 150-year-old pensioners, seemingly bizarre scientific research topics. And yet, no pensions were actually being paid to the long-deceased, and the so-called “transgender” (actually transgenic) mice were part of crucial medical research. Many of the bureaucrats and researchers who were laid off turned out to be essential to government functions.

Finding clear inefficiencies in the American federal apparatus proved more difficult than anticipated. DOGE’s results were modest at best, and their promises of significant cost savings are unlikely to be fulfilled. Certainly, there is room for optimization — but it must be carried out carefully and with input from seasoned experts. Simply bringing in programmers and data analysts from outside is not enough.

Will inflation save the day?

In Russia in the 1990s, payments on massive government debt consumed the state budget. To meet its obligations to citizens, the state had to either borrow more or monetize the debt — that is, pay salaries and pensions with freshly printed money. The result was inflation and the devaluation of the ruble.

The situation in the U.S. is much less severe. Theoretically, a U.S. default on existing debt is impossible given that the government can always “print” more dollars to repay what it owes. In reality, however, the matter is more complicated.

Theoretically, a U.S. default on existing debt is impossible given that the government can always “print” more dollars to repay what it owes — but the reality is more complex

First, monetizing the national debt is a form of default in itself. Creditors receive their payments in devalued currency, meaning their real returns are lower than expected. An important question is: who are these creditors? According to recent data, about 30% of U.S. government debt is held by foreign entities — whether individuals or institutional investors. The remaining 70% is owned by Americans or U.S. institutions such as corporations, pension funds, and banks. Inflation benefits the government but effectively robs its own citizens.

Second, inflation only helps to pay off existing debt. Borrowing in the future becomes more difficult and expensive due to the fact that expected inflation is factored into interest rates, which rise accordingly. When the federal government must continuously borrow to service past debts, inflation only worsens the situation. For the same reason, opting for outright default on obligations is akin to shooting oneself in the foot.

Third, in all developed countries, decisions on money issuance are (thankfully) made not by the president or executive branch, but by independent central banks. The Federal Reserve’s committee has a dual mandate: to maintain price stability (keeping inflation low) and to control unemployment. These goals fundamentally conflict: tight monetary policy keeps prices stable but slows the economy and risks higher unemployment, while loose policy stimulates growth but risks inflation. The Fed seeks a balance between these objectives. Resolving budget deficits is not part of the Federal Reserve’s mandate.

Currently, the Federal Reserve believes it is too early to shift to a loose monetary policy, and Jerome Powell has resisted President Trump’s calls to do so. Significant cuts to government spending, as envisioned by Trump, could have triggered a recession — something that has not yet occurred. However, if the U.S. economy shows clear signs of an impending slump, interest rates may be lowered.

In summary, if the debt problem is to be solved, structural reforms to both the tax system and budget expenditures are unavoidable. A reliable, long-term plan is needed to balance revenues and expenses.

Bad news for Americans

In the U.S., both the share of government spending in the economy and the overall tax burden on the population are lower than in most developed countries. This is a deliberate choice and a source of growth and development. It’s no secret that the business climate in America is far more favorable than in much of old Europe. The U.S. attracts investments, skilled workers, and technology from around the world, fueling its economic growth.

However, the U.S. faces stiff competition from other jurisdictions. Several offshore havens offer corporations very low tax rates, making it difficult for Washington to increase the revenue it collects from businesses. Corporations are mobile, especially on paper.

Companies can flee taxes to offshore havens, but the population cannot — which means ordinary people will ultimately bear the cost

That is why the backbone of federal revenue comes from taxes on individuals: income taxes and payroll taxes, which fund Social Security pensions and healthcare for the elderly. Unfortunately for taxpayers, any realistic budget-balancing plans collecting the money from ordinary people, and such measures will have to be implemented sooner or later.

A quick look at the structure of revenues and expenditures makes it clear there is no reliable alternative. Although the tax burden on U.S. wages is significant, it remains substantially lower than in Europe.

There is another way in which government debt is similar to living on credit. As in a family, if the older generation has taken on loans it cannot repay, it passes the burden onto the younger generation. For now, the U.S. is postponing debt payments, but sooner or later, future generations will have to confront this problem.