On April 10, at NATO headquarters in Brussels, representatives of the so-called “coalition of the willing” gathered for another meeting. This informal alliance of mostly European countries is composed of states that have voiced their readiness to deploy troops to Ukraine after a peace agreement is reached. Led by France and the UK, the project increasingly appears poised to evolve into a pan-European armed force — potentially Europe’s long-term response to the foreign policy unpredictability of the United States. Still, in the event of a direct military confrontation with Russia, going into battle without U.S. support would be difficult: Europe currently lacks carrier strike groups, cruise missile launch platforms, and long-range radar systems.

While the U.S. continues to engage in peace negotiations with Ukraine and Russia, Europe is working to define its own role in shaping what will likely become the future security architecture of the region for decades to come.

A central question involves the presence of a European military contingent in Ukraine and, in the longer term, the potential creation of a “European Army” based on this structure — an army capable of replacing U.S. forces should a fully isolationist approach take hold in Washington.

Since February 2025, meetings at various levels and in different formats have taken place to discuss the idea of deploying a unified European troop contingent to Ukraine. Notably, on April 5, British Chief of Defence Admiral Tony Radakin and French Chief of Staff General Thierry Burkhard met with President Volodymyr Zelensky in Kyiv to discuss the size, organizational structure, and components of the prospective international force in Ukraine.

Another meeting of the “coalition of the willing” was held on April 10 in Brussels, where over 30 countries expressed their readiness to participate in postwar stabilization. Given that such efforts inevitably touch on broader European security, the coalition is also seen as a prototype for a new military alliance — one that would function with strategic autonomy from the United States.

At the Munich Security Conference this past February, President Zelensky called for the creation of a united European army. He argued that such a force should serve both to deter the Kremlin and to gradually replace the contingent of U.S. troops currently stationed in Europe. Later, in an interview, Zelensky stated that Europe and the U.S. should jointly fund the Ukrainian army, which would take on the role of defending Europe against the threat of Russia.

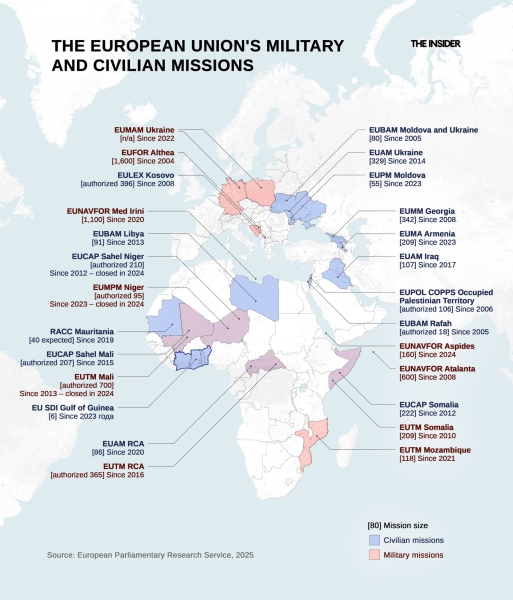

Joint security projects have been under discussion in Europe since the early 2000s, particularly under the frameworks of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). Most EU member states are also members of NATO, but growing instability along Europe’s borders has prompted renewed interest in launching military initiatives from within the EU itself.

Currently, the EU oversees 23 military and civilian missions involving around 3,000 troops and 1,000 civilians. Since 2003, more than 40 missions have been deployed not only in Europe, but also in Africa, the Caucasus, and the Middle East. While most focus on observation, assistance with reforming local security forces, and training, some have operated under direct military mandates.

The Defense Forces of Ukraine is a collective term referring to all Ukrainian security agencies involved in combat operations. In addition to the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU), this includes, in particular, the National Guard, the State Border Guard Service, the National Police, the Defense Intelligence of Ukraine (HUR), and the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU).

The largest to date is the EU Military Assistance Mission in Support of Ukraine (EUMAM UA), which was launched in November 2022. The mission, managed from Brussels, is aimed at training Ukrainian forces in Europe. Thus far, 73,000 Ukrainian soldiers have received training through EUMAM, and the mission has since been supplemented by other EU initiatives, such as the Act in Support of Ammunition Production (ASAP) and the European Defence Industry Reinforcement through Common Procurement Act (EDIRPA) — both designed to boost the EU’s military industrial capacity.

The idea of sending European troops to Ukraine was first publicly proposed by French President Emmanuel Macron in 2024. Then in early 2025 British Prime Minister Keir Starmer published an article in The Telegraph stating the UK’s principled readiness to send British forces to Ukraine as a security guarantee in the post-war period.

On February 24, Starmer introduced the concept of a “reassurance force.” The naming matters here, as the mandate and objectives of these contingents would differ from that of traditional peacekeeping missions or of the multinational operations previously seen in Iraq and Afghanistan (even if the “coalition of the willing” moniker was chosen as a clear nod to the events of 2003). Likely names for the Western contingent in Ukraine include Multinational Force Ukraine (MFU) or the Enhanced Stabilization Force in Ukraine (ESF-U).

This mission would differ fundamentally from EU-led, UN peacekeeping, or U.S.-led multinational forces, as it would actively support one party in the conflict. It would also need to establish a system of military guarantees capable of deterring the Kremlin — without the participation or even indirect backing of the United States.

The Defense Forces of Ukraine is a collective term referring to all Ukrainian security agencies involved in combat operations. In addition to the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU), this includes, in particular, the National Guard, the State Border Guard Service, the National Police, the Defense Intelligence of Ukraine (HUR), and the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU).

This mission would differ fundamentally from UN peacekeeping forces, as it would actively support one party in the conflict.

Following numerous meetings and negotiations among coalition members, the outlines of a potential European military mission in Ukraine have begun to emerge thanks to official statements and informal leaks from senior officials.

Key elements of the plan include:

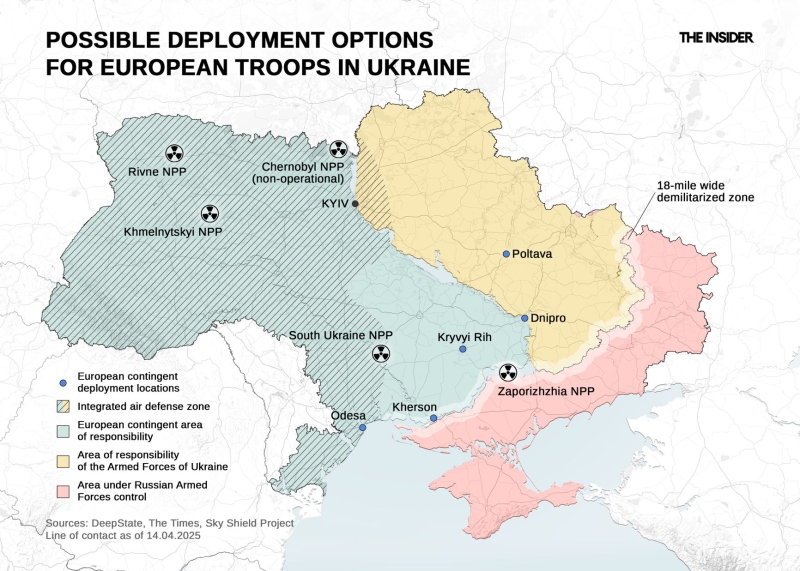

- Deployment of troops outside the combat zone, stationed in strategic cities and ports behind the front lines.

- Focus on air and naval components — areas where Ukraine’s armed forces lack experience and logistical capacity.

- The creation of a demilitarized zone along the line of contact, estimated to range from 12,000 to 96,000 square kilometers, requiring both Russian and Ukrainian forces to withdraw some distance from their current positions.

The mission is said to be aimed at four primary objectives:

- Safe skies

- Safe seas

- Peace on land

- A strong Ukrainian military

The Defense Forces of Ukraine is a collective term referring to all Ukrainian security agencies involved in combat operations. In addition to the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU), this includes, in particular, the National Guard, the State Border Guard Service, the National Police, the Defense Intelligence of Ukraine (HUR), and the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU).

Given that Ukraine’s Defense Forces number roughly 1 million personnel, and Russia’s military presence in Ukraine is estimated at 600,000, a European deployment of 20,000–30,000 troops stationed in the rear — across a 1,000-kilometer theater — would have no direct military impact. Thus, the European contingent is expected to focus on capabilities the Ukrainian military cannot yet provide: air and naval patrols and intelligence gathering.

Such a European force would not take a neutral stance but explicitly align with Ukraine. From the outset, the troops would also be intended to serve as a deterrent force, signalling that further escalation could draw coalition members directly into conflict with Russia.

Maintaining a 40,000-strong contingent for a decade would cost an estimated $40 billion — not including support for Ukraine’s own forces, help with post-war reconstruction, and direct budgetary aid to Kyiv.

The UK-led Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF), which links up the military capabilities of Great Britain with those of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden might play a role in post-war Ukraine. Alongside France, these countries could plausibly contribute 40,000–50,000 troops. However, the issue of funding has yet to be determined.

For comparison, after the Bosnian War, 60,000 NATO peacekeepers were stationed in a far smaller area. Analysts suggest that to effectively deter Russia, a force of 100,000 to 150,000 troops would be required to be on the ground indefinitely.

The Defense Forces of Ukraine is a collective term referring to all Ukrainian security agencies involved in combat operations. In addition to the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU), this includes, in particular, the National Guard, the State Border Guard Service, the National Police, the Defense Intelligence of Ukraine (HUR), and the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU).

To effectively deter Russia, a force of 100,000 to 150,000 troops would need to remain on the ground in Ukraine indefinitely.

One proposed alternative is a purely aerial mission, tentatively named “SkyShield,” which would establish an Integrated Air Protection Zone over western Ukraine. European aircraft — up to 120 jets — would patrol the skies, safeguarding civilian infrastructure and population centers from Russian airstrikes.

SkyShield does not require European boots on the ground in Ukraine and would commit to protecting solely to the country’s western regions. Proponents argue it could have greater practical impact than deploying 10,000 ground troops.

At the most recent coalition meeting in Brussels, only six countries — the UK, France, the Baltic states, and one unnamed nation — expressed their readiness to deploy troops to Ukraine.

The Defense Forces of Ukraine is a collective term referring to all Ukrainian security agencies involved in combat operations. In addition to the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU), this includes, in particular, the National Guard, the State Border Guard Service, the National Police, the Defense Intelligence of Ukraine (HUR), and the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU).

Only six countries — the UK, France, the Baltic states, and one unnamed nation — have so far expressed their readiness to deploy troops to Ukraine.

Experts note that U.S. consent remains a key condition for deploying any European contingent to Ukraine, and no nations have expressed a serious willingness to put its troops in harm’s way before a formal peace agreement is signed. Without adequate security guarantees, stabilizing eastern Europe after the war will be difficult, and aside from a military presence, Europe has little else to rely on.

A reduced U.S. role in Europe’s security architecture would inevitably lead to a transformation of NATO and a rethinking of the EU’s own military capacity. Discussions are already underway about downsizing and relocating U.S. forces in Europe, including a possible withdrawal of half of the 20,000 troops stationed near the border with Ukraine.

There are differing views among NATO and EU members, and some officials have floated the idea of a new format — akin to the European Defence Community (EDC) proposed in 1952 but never ratified, as NATO ultimately absorbed its functions. Today, the “coalition of the willing” and the Ukraine Defense Contact Group may evolve into the foundations of a European defense structure independent of the U.S. and NATO.

On paper, European armies collectively number about 1.5 million troops (excluding Turkey). In reality, Europe remains deeply dependent on U.S. military power in critical areas.

Only France and the UK have carrier strike groups, and even those are far less capable than those of the U.S. Without American sea-launched platforms like Tomahawk missiles, Europe has very few alternatives — either submarine- or surface-based — for cruise missile deployment. Anti-submarine warfare capabilities, coastal defense systems, and long-range radar detection are all severely limited. Europe would also face major challenges in intelligence gathering on Russian ballistic missile launches. Nuclear deterrence would also become an urgent question if U.S. guarantees are no longer seen as binding — whether under Trump or a like-minded successor.

Regardless of size or mandate, the deployment of a European military contingent to Ukraine would be historically significant. A mission carried out without U.S. involvement — or even against the wishes of the sitting U.S. administration — could be the first step on the way to a truly independent European armed force.

Military analysts estimate that in the event of an open war with Russia, Europe would need the support of approximately 300,000 American troops — around 50 heavy brigades, with thousands of tanks, armored vehicles, and artillery systems. If that guarantee is no longer assured, Europe will need to build such a capability on its own — integrated from the start into unified command and logistics systems.

Such a deployment in Ukraine could become the basis for building a future European Army, independent from the U.S. and capable of defending the continent. But achieving such an outcome will require years of planning and the development of a robust defense industry.

The Defense Forces of Ukraine is a collective term referring to all Ukrainian security agencies involved in combat operations. In addition to the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU), this includes, in particular, the National Guard, the State Border Guard Service, the National Police, the Defense Intelligence of Ukraine (HUR), and the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU).